Recently, an organization called Third Way, comprised of conservative Democrats and their corporate donors, sent out a list of “forbidden terms” that people on the political left should avoid, lest the Average Voter think we are crazy or out of touch. These terms include “birthing person,” “unhoused person,” “Latinx,” “cis,” “heteronormative,” “structural inequality,” “LGBTQIA+,” and so forth. The attempt to police these terms is, of course, Orwellian, an assumption that if you remove the language for explaining certain things, those things will no longer be thinkable. Instead of trying to address the needs of those who are connected to these terms, just wipe them away, or deprive them of the dignity of existence. Problem solved!

Historically, the arts have been a refuge from that kind of thinking. At their best, they have provided a kind of social laboratory where such ideas and identities could be formed. That’s because art, unlike broad social discourse, is a means for expressing impulses and desires that have not yet found their precise explanations. We tend to feel these social needs before we can describe them, largely because we often come to understand who we are and what we want not by having those needs satisfied, but by having them unmet. We engage with a dominant culture and find that we don’t quite fit, that demands are being made of us to which, for some reason, we cannot or do not want to conform. Art is a very good tool for articulating this friction.

This is probably why the political regime that has taken over the United States is taking action to limit the public funding available for this kind of exploratory art. The National Endowment for the Arts, which has never been a bastion of radicalism, has now taken to canceling grants for both individuals and institutions that do not conform to the Trump agenda, which includes restrictions on so-called “gender ideology” and “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” The fact that we completely understand what the administration means by this — no money for art that addresses the experiences of non-white and/or queer people — should not distract us from the language games being played here. The American far right can use “DEI” and “gender ideology” as code words that denigrate entire populations, but post-Clintonian corporate Democrats warn the left not to use terms like “heteronormative” or “structural inequality” in order to describe the ways that the far right is working to eradicate said populations. In other words, only one side of the political spectrum is permitted to use crazy, out-of-touch language to get its work done. The two prohibitions fit together so neatly that it could lead you to think that maybe they are all part of the same overall agenda of social cleansing.

Arts organizations often rely on government grants, or on corporate monies whose donors take their cues from the regime currently governing. So rather than challenging these sweeping executive orders and political decrees, organizations and administrators very often try to thread a very particular needle. They seek to conform to those demands (which do express their own social preferences to a greater or lesser degree) while maintaining an outward appearance of liberal defiance and free-speech oppositionalism (which is what these institutions’ user base expects of them, at least tacitly). This balancing act, which is really no kind of balance whatsoever, tends to happen in terms more economic than overtly ideological. The capitulation to fascism — because let’s be clear, that’s what it is — takes the form of “unfortunate cutbacks,” “greater investment in AI technologies,” “adjusting institutional mission,” and the classic “need to do more with less.”

This has not, however, been the case with the Crossroads Festival. It has remained the most expansive showcase for experimental media in the United States, and stands alongside Mexico’s FICUNAM and Canada’s Images Festival as one of the premier exhibition points for artists’ filmmaking in North America. One of the consistent strengths of Crossroads’ programming is its breadth. Artistic director Steve Polta has shown unwavering support for newer and emerging filmmakers, many of whom have received their first public screenings at the festival. Considered on a film-by-film basis, Crossroads has sometimes been a mixed bag, a combination of stronger and weaker films. But it seems to me that this is part of the point. Polta is committed to nurturing new talent and, above all, getting the work seen. It’s a sizeable festival that nevertheless feels curated by a specific sensibility, in the tradition of Mark McElhatten and Gavin Smith’s “Views from the Avant-Garde” programs.

It hardly seems coincidental that some of the most powerful films in this year’s Crossroads festival are ones whose makers are exploring those now explicitly forbidden areas of social inquiry. Like much of the greatest art throughout history, these films are attempts to concretize forms of affect relating to life on the margins of majority society. This is crucial, because while we are witnessing an explicit effort to erase the words and concepts that have developed in response to marginalization and oppression over the last century, it is vital that artists begin the process of finding new languages with which to describe the new pressures that we feel, and the emergent identities that will form, and eventually triumph, in the crucible of this latest attempt to unwrite history.

Program 1: temporary near thing / pulsebeat promises

Good festival programming is always about how films dialogue with each other, and not just about their individual character, but this aspect emerges especially strongly in blocks of experimental shorts, where the program itself becomes something of a statement. In its least thoughtful (but most common) iteration, this can be simply a division by genre or topic: here are the documentaries, here some animations, and over there some films about race and gender. Crossroads achieves much more than this, both in overall selection and within each program, highlighting intersections of formal and thematic ideas that make every film easier and more interesting to engage with.

The first film in this year’s Program 1 is the oldest in the festival, the only one from the 20th century: Ken Jacobs’ Flo Rounds A Corner from 1999. In its elongation of a few seconds’ of action into six minutes of film, it recalls the birth of Jacobs’ structuralism in Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (1969), but it’s also the first of his “eternalisms” films, which use series of alternating stereoscopic images and color oppositions to create a three-dimensional, perpetual motion effect out of limited source material. Most people attending a festival like Crossroads will be familiar with some of these works, but opening the program with this selection frames the works that follow.

Some of those works are clearly in direct conversation with Jacobs. Scott Stark’s Tulsa, for example, uses stereo, still photos of 1950s parties in a very similar stroboscopic way. Sometimes the strobe uses two entirely distinct source images, where initially it achieves something of the eternalism perpetual motion effect. At other times, the photos are of the same scene, but with a slightly different angle of view. Here, objects in focus (human figures and still lifes, mostly) become jittery but still relatively stable, while the background wavers much more violently. The result is a physical detachment of foreground from background such that objects appear cut out and repasted into an alien environment.

Later in the film, Stark departs from the basic conceit and begins playing comically with his images, making a face or an item of clothing zoom forward and consume the screen. The two-scene strobes begin combining human figures in grotesquely funny and even disturbing ways, giving one person another’s hair as a wig and making a man perform fellatio on a bottle. The images themselves move from the convivial to the disquieting. A man lies on the floor with an arrow in his chest, presumably play-acting. Well-dressed men and women who have appeared in several party scenes now pose alongside poorly clothed Black and Brown people and tiger pelts, tourists in the Global South, before we return to celebratory pin-ups of President Eisenhower and the American flag. The party games have become something else entirely.

Zachary Epcar’s Sinking Feeling also works to estrange familiar spaces. The film shows scenes of commercial and office spaces with sharply angled architecture and dim fluorescent lighting. Meanwhile, three unseen characters narrate their experience of getting trapped on a stopped subway train. This ordinary event is described in the most ominous, almost apocalyptic terms, as the darkness of the train car carries its passengers into equally dark psychosexual territory. As the narrators recall spitting into each other’s mouths and whimpering in animal frenzy, giving up and awaiting men “in their hazmats [to] harvest the jizz from our lifeless bodies and go,” we continue to view the forlorn emptiness of the business building, hands performing routine tasks, workers standing still and staring out of their windows, passed out on a copying machine. A lifeless body is dragged across a room, someone microwaves a frozen meal. The political overtones are clear enough: “How long will we keep debasing ourselves before they’re satisfied?” one of the characters asks near the end, while a security guard observes every corner of a building through monitors. But Epcar’s real achievement is not the observation that capitalism’s built spaces are dystopian, but the less explicable beauty he finds in shape and light. A macrophotographic sequence of an orchid and a smoky pink-to-white gradient of light across window blinds are two of the more poignant sequences, before the film ends with the ugliness of security cam footage.

Kevin Jerome Everson similarly finds formal beauty in social ugliness in his film Boyd v. Denton. Filmed at the Ohio State Reformatory (a prison closed in 1990) and named for a district court case filed by inmates about poor conditions there, the film uses a rapid montage of black-and-white photography to create a familiar sort of flickering abstraction. Beautiful in its own right, the technique does not erase the horrors of its source material, which, if anything, are emphasized in their barren, rusted ghastliness by an approach that never allows the images to settle. As with all of Everson’s work, Boyd v. Denton invokes not just the form but the history of cinematic art: this prison served as a primary location for Shawshank Redemption, among other films.

Sofia Theodore-Pierce pushes even harder (and even more playfully) on conventions of spatial representation in Half Halt. She works with a handful of basically simple materials — two friends talk as a lift ascends and descends, someone reads their poem, the artist films and is filmed while riding a horse — but jumbles these materials into intricately complicated combinations. We hear the elevator while seeing a blank screen, see the elevator while hearing what seems to be a train, witness the poetry reading at a maddening off-sync delay, and finally watch the frame freeze altogether and simply end without resolution as if the file were corrupt. Formally, we are denied every expected satisfaction, including any direct articulation of theme; the film works through a constant skirting around, showing us how it was made but not what it’s about. But every sound and image is tied together by the friendship of the artist and her collaborators, offering a comfort and support that the edit does not.

These works — and they’re all in just the first program! — exhibit the marvelous variety of formal means available for moving image artists to explore space, geography, architecture, community, history, and endless other themes. The ideas raised in this first program are echoed throughout the others in the festival: Janie Geiser’s Slideshow repeats the use of mid-century found photography; Greta Snider’s In the Maritime Frequencies has multiple unseen narrators complicate loosely related images; Jodie Mack’s LOVER, LOVERS, LOVING, LOVE closely studies flowers in macrophotography; and so on. You could draw such comparisons for every film in the festival, and all of them benefit from being seen in conjunction. The films work not just on their own, but as collective commentary on what cinema can be. This speaks not just to the caliber of the programming here, but to the value of the avant-garde in general, and why it’s so important to have places to see and discuss films like these. — ALEX FIELDS

“Man number 4,” from Program 6: hold me in your arms

Miranda Pennell’s Man number 4 is a film composed of a single image, which acts as a stage for a narrator to inspect only several hundred pixels at a time. A cursor is present, guiding the focus of the film along a pre-ordained path, zooming in and out of the photograph according to the amount of information that the narrator will present about any given selection. The single-image film is a simple conceit, with diverse mastery demonstrated in such films as A Casing Shelved (1970), wherein Michael Snow names every item in a still photograph of a shelf in his garage; Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), which is composed of an unchanging blue background; and One (1999), a flicker film by Fred Worden, which smashes a single frame of the moon into itself to cosmic ends. Man number 4 begins in “reddish sand and earth,” slowly tracking along a blue-ish cloud of pixels unidentifiable if not for the narrator’s explanation that these are “hundreds of men” located inside a pit. The revelation of soldiers and military vehicles overlooking the huddled crowd reveals the geography of the scene: Beit Lahia in Gaza. The examination of the image as forensic evidence of the ongoing genocide is reminiscent of the film work done by Forensic Architecture, a research agency that has been publishing video analysis of Israel’s occupation of Palestine for more than 14 years.

Five Palestinian hostages are present in the foreground, man number 1 suspended in alien brightness from an Israeli spotlight. Pennell credits Twitter user “techjournalist” for uncovering the geo-data to verify the image’s location and the identity of Man number 4, Dr. Khalid Hamoda, whose wife and child were killed before he was abducted. The investigation of the photograph is interrupted by “Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor, K. 626: I. Introitus,” which plays as the narrator ends the film, interrogating the role of the viewer in the image: “and you, sat here, listening to gentle music as you look on.” The music isn’t just “gentle.” The liturgical lyrics plead:

Grant them eternal rest, O Lord,

and may perpetual light shine on them.

Thou, O God, art praised in Zion,

and unto Thee shall the vow

be performed in Jerusalem.

Hear my prayer, unto Thee shall all flesh come.

Grant them eternal rest, O Lord,

and may perpetual light shine upon them.

Program 7: for all the seasons of your mind

Program 8: the mountain replies with an echo

The sheer breadth of Crossroads’ programming is a double-edged sword. There is a wide variety of styles of experimental film, but the festival as a whole can be hard to navigate, and it’s possible for small or unassertive films to get lost in the shuffle. This is especially the case with younger or developing filmmakers whose works can be tentative, lacking the bolder assertions of works by more established makers. Among the 12 films in Programs 7 and 8, the strongest works are in fact by veteran filmmakers who have found new ways to adapt the aesthetic languages they have been developing for many years. The latest films by Jodie Mack and Cauleen Smith are immediately recognizable, but the artists have allowed their signature approaches to evolve, all the better to address our very unique moment in human history.

Lover, Lovers, Loving, Love finds Mack once again working with isolated and deconstructed flora of the sort that we saw in her recent Wasteland series, and its unofficial coda M*U*S*H. These works represent a new phase in Mack’s filmmaking, wherein the various kinds of patterned textiles that organized her best-known films have been brought into visual conversation with the natural materials that inspired those patterns. Through single-frame photography and rapid alternation of visual information, Mack “animates” inert objects, activating them in the eye with a sort of comparative maximalism. Lover, Lovers, Loving, Love adopts a more rigid, more patient organizational structure that, like the title itself, slowly conjugates the plant material into distinct forms. We see rotating flowers on the stem, then superimpositions of different flowers, and eventually dense collections of petals and leaves. Mack then introduces close-up shots of textile patterns, pulsing the collated material in a blender of montage. The film opens and closes with plant matter suspended in water, suggesting a recursive series of deluges, a form of destruction that also permits unexpected waves of color and texture. L4 represents Mack’s most overt conversation with the flicker films of Paul Sharits, using a macro-level separation to intensify the chaos on the level of the film frame.

Like Mack, Cauleen Smith adopts some of the procedures of experimental animation to generate films that transcend that category. This is something Smith has been doing ever since Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (by Kelly Gabron), the 1992 film that first announced Smith as a major figure. Mines to Caves is the earliest of three films that Smith is now presenting as a feature-length project called The Volcano Manifesto, and it’s a film that engages with geological time in order to explore the landscape from an ecological standpoint, decentering human subjectivity in favor of animals, stones, and sky. Smith introduces a slight stutter into her images, overlaying them with the haze of Ben-Day printers’ dots, lending Mines to Caves the character of a timeworn, excavated document. The film shows the remnants of an abandoned mineshaft, the nexus of capitalism’s plunder of the natural world. Smith’s voice exhorts the earth to reclaim these spaces, to transform the mines back into the caves they once were. Stressed, high-contrast images show the destructive power of mining and smelting, and gradually show various animals reestablishing dominion over their stolen land. Smith’s images caress the craggy minerals, their nooks melding with the spaces in the dot-matrix pictures themselves. Rather than inert commodities awaiting human extraction, the materials gain their own subjective existence apart from human life. Smith’s fragmented voiceover chants the names of various minerals — “gabbro, lodestone, epidote,” etc. — while surveying the wildlife, asserting a connection between rock and fauna that excludes human calculation. It is a bracing, incantatory work, made all the more powerful by the timbre and rhythm of Smith’s narration.

Other films in the two programs are less successful overall, but not without promise. Bosco, by the French duo of Stefano Canapa and Lucie Leszez, skillfully applies optical printing and differential focus to produce a set of abstract variations on a tree. Although a bit too reminiscent of many Austrian films, especially the works of Peter Tscherkassky, Bosco is crafted with skill and precision. I Think I Said “Yes” by Spanish filmmaker Pere Ginard, is an animation collage that plays with the fragmentation and significations of the human body. Ginard shows a good sense of shape, manipulating his assembled images with a pulsing, nervous energy, but the work leaves more of an impression in terms of atmosphere than idea. Derek Jenkins’ Letter from Blackhawk Island is an impressionistic documentary miniature, centered on the Wisconsin home of poet Lorine Niedecker, a woman who lived in relative isolation despite maintaining active correspondence with major literary figures, including Louis Zukofsky. At just over two minutes, Letter feels less like a complete statement than a component of a larger project. And under the flower moon by Craig Scheihing is a dense, painterly nature study that plays with streaks of light generated by close-ups of water droplets and foliage. This is a film that contains a number of different compositional approaches, and while flower moon is never less than appealing, it shows less focus than Scheihing’s earlier films sunspots, burnt into my heart and to open a window. The strongest element of the new film is its use of sound. Scheihing uses a recording of distant vehicles on a highway, an ironic contrast to the visual material, which is mostly confined to sylvan forms.

As I have addressed elsewhere, the experimental scene has changed in recent years. Whereas millennial filmmakers often found their voices in the landscape film or the so-called “avant-doc,” a newer generation seems much more comfortable with the word and image interplay of the film essay. There are several possible reasons for this, including an epistemological shift wherein filmmakers who have lived with the Internet their entire lives perhaps expect images, words, and sounds to accompany each other, rather than representing a set of tools one may use or leave aside. As we know from the very best work in this mode, from Marker and Trinh to Biemann and Galibert-Laîné, it is a difficult genre to master.

One of the common pitfalls of film essays is an overdependence on language. From a cognitive standpoint, if words are onscreen, they are likely to take center stage, even if the intent is to integrate them with images and sounds. Of course, genres evolve and viewers evolve along with them. An increasingly common element of contemporary productions, as seen in All Said Done, Micah Weber’s poignant memorial to his father, is the subtitling of English-language narration. It’s a way to avoid ablism and increase accessibility for a broad viewing audience, something that has become standard practice on platforms like TikTok. This is a laudable development, but from a compositional perspective, it introduces new challenges. The subtle, muted images in Weber’s film are partly disrupted by the onscreen text. And while a certain type of classicist aesthete would say that the subtitles ought to be removed — I refer you to old arguments around Anthology Film Archives’ “Essential Cinema” series — I strongly disagree. However, filmmakers need to find creative solutions to this problem going forward. After all, experimental film distinguishes itself by setting a higher bar to clear. Images are not merely denotative or informational; they perform more work than that. So it’s incumbent on artists to discover radical new ways to employ text as a compositional element.

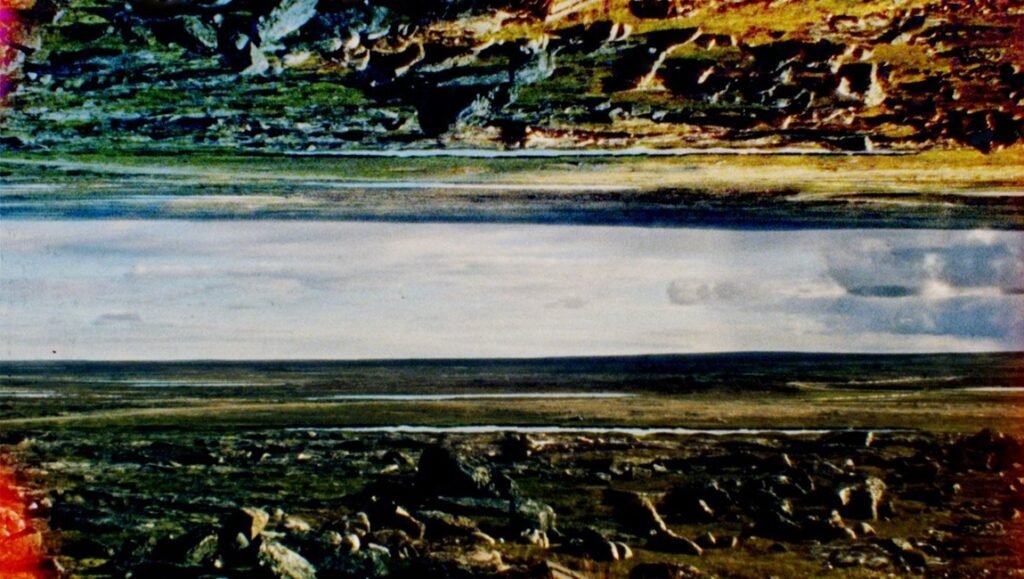

Two films, one from Program 7 and one from Program 8, stake out very promising creative territory while falling prey to the common tendency to allow language to override other types of meaning. While Sam Drake’s film Suspicions Around the Hidden Realities of Air shows that the filmmaker has considered onscreen language as a visual mode, the film suffers from a rather straightforward visual narration that nudges the images, and especially the sounds, into the back seat. Drake’s steady stream of landscape and urban locations serves an illustrative function, subordinated to her consideration of Cold War radiation experiments. The film’s historical and political aims are clear and admirable, but one gets the sense that the avant-garde format was not necessarily integral to the project. Somewhat more fully realized, Lindsay McIntyre’s Tuktuit (Caribou) examines lichens and the Canadian tundra, before turning its attention to the skinning of a caribou and preparation of its hide. Tuktuit is impressive as a rhythmic document, easing the viewer gracefully from flora to fauna, emphasizing the continuity between the two in Inuit life. However, McIntyre’s use of onscreen text errs on the side of over-explanation. It is clear that Tuktuit means to balance poetic and documentary aspects, but this makes it that much more important that the film trusts its viewer to find their way through the material.

A much more successful example of this interplay between word and image is I Carry the Universe Within Me by Cherlyn Hsing-Hsin Liu. It is a film of such readily apparent beauty that at first glance, a viewer might not notice how densely structured it is. Combining grainy black-and-white images with fragments of poetic text (in both English and Chinese), Liu also uses staccato editing and shadowy superimpositions to break the visual track apart into components of motion and stillness. The text is in part about the historical distance between the viewer and the speaker — a thousand years to be exact — and so I Carry the Universe gives the impression of several signification systems in collision, with a distinct time lag that forestalls any easy synthesis. This is a film to get lost in, one that courts confusion but never frustrates.

I want to conclude this review by addressing two films by the Kiowa filmmaker Adam Piron. In a relatively short time, Piron has emerged as one of the most vital new voices in contemporary experimental film. Given the current social and political landscape, it stands to reason that many filmmakers have a strong desire to produce focused, engaged work. Turning to experimental film makes sense in this context, since conventional forms of communication have already been co-opted by the mass media — the formal stereotypes that Peter Watkins has called the “monoform.” Piron’s films offer an object lesson in artistic radicalism. His film Black Glass is organized around a series of stereoscopic images shot by proto-cinema pioneer Eadweard Muybridge that were commissioned by the U.S. Army to illustrate their war against the Modoc tribe in the 1870s. Since the Native combatants did not make themselves available for this photo shoot, Muybridge had the Army’s Native scouts pose as Modoc people. Piron displays Muybridge’s images, linking them together with abstracted moving images of the areas where the battles were fought. Using settler colonialist propaganda against itself, Black Glass recalls similarly incisive works by Ken Jacobs, such as Capitalism: Slavery and Capitalism: Child Labor.

The Early Sun, Red as a Hunter’s Moon, from one year earlier, combines footage Piron shot in Portugal with the writing of N. Scott Momaday and, most strikingly, excerpts from a 1890 letter sent to a Kiowa student named Belo Cozad. Officials in a school in Pennsylvania wanted Cozad to translate the “hieroglyphic script” found in the letter. Momaday’s text anchors the bottom of the screen as Piron superimposes the whirls and curlicues of the visual language over the filmed record of his own movements through Porto. Much like I Carry the Universe Within Me, the result is a complex system of sign systems, each unfurling within its own distinct temporality. Piron generates intersecting timeframes, the historical and archival material brushing against his own present-day existence as an Indigenous man. Cozad’s translations, at first rather amusing in their ordinariness, serve to emphasize Piron’s critical point. Every historical personage was once a contemporary, and we will, in turn, become traces in history. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Comments are closed.