First Light

Nearly five years ago, Filipino-Australian filmmaker James J. Robinson hit the headlines after breaking into his alma mater St Kevin’s College, Melbourne’s elite all-boys Catholic school, and setting his old blazer alight on campus grounds as an act of protest against the toxic “hypermasculine culture” historically inherent in same-sex Catholic schools. “St. Kevin’s is just a microcosm of everything else that’s happening in the rest of the world,” he told VICE. It’s an inevitable, and perhaps limited but certainly not disingenuous, point of entry into his directorial debut First Light, now playing at Rotterdam’s Harbour Programme, in that it equally, deftly taps into some awful and systematically upheld secrets of the Catholic Church as an institution. The film, though set in a different context, feels definitely spurred by the filmmaker’s lived experience growing up queer and Catholic, bearing witness to the many ways religion is weaponized to tolerate injustice. For a first feature, Robinson’s style is already impressive and astute.

The colonial mountain community in which the languidly picturesque movie takes place is similarly rendered as a microcosm of something far more sinister. Beneath the sprawling landscape that softly, splendidly comes alive at first light is a rot that spoils the air. Here, the nocturnal beings troubling a young, inquisitive nun seem conspicuously ominous, just as the constant murmur of the weather and the indecipherable voices that intermittently punctuate the film always feel like something’s lurking in the distance. Robinson seems deeply attuned to what the textures of the earth reveal about the people that inhabit it, giving the story a kind of organic, elemental allure.

First Light spends most of its time shadowing the quadragenarian Sister Yolanda (Ruby Ruiz), who lives in a rustic Spanish-built convent already on the verge of collapse and tends to sick patients at the local hospital. At the same time, she looks after the young, homesick novice Sister Arlene (newcomer Kare Adea) and frequents the dying mother of Linda (Maricel Soriano), the wealthy wife of the local construction firm owner Edward (Rez Cortez) — both generous patrons of the local church, whose stately condition contrasts that of the poorly-maintained nunnery. Yolanda devotes her life to putting the needs of others before her own, always wearing a warm smile. And although she came of age in a neighborhood just a jeepney away from the close-knit community, life in the convent has practically erased memories of her past, which only vividly resurface following a terrible accident, involving the young construction worker Angelo (BJ Forez). On the day of the tragedy, Yolanda is asked by a suspicious cop (Apollo Abraham) to deliver last rites on Angelo, who is still alive but has been strangely abandoned by doctors in the emergency room. Seeing the horrified man on his deathbed, Yolanda begins to question the nature of the accident, the integrity of the people around her, and, eventually, the belief system that has both kept her in the dark and kept her going for decades.

Proceedings are by turns softened and escalated by the soundscape of the rural milieu and by composer Ana Roxanne Recto, who experiments with the cello and guitar among other instruments, to sublime effect. The nun soon plays detective, bringing her closer to the source of her unrelenting unease. She tries to connect the dots by visiting the likes of Cesar (Emmanuel Santos), the victim’s father, and local priest Father Claridad (Soliman Cruz), who refuses to hold the dead man’s memorial in the church, citing a reason unbecoming of a servant of God: Angelo has never shelled out a fortune in donations as much as the other churchgoers. This quest allows First Light to unfold as an atypical crime procedural by way of Robinson, which means a poetic and slow-burn approach to articulating harsh truths about a society mired deep in impunity and institutional corruption. But the director is less concerned with resolving the crime at hand or detailing its dramatic specifics than he is with heightening the disillusionment that hacks through the veritable paradise. (That parts of First Light were shot in the northern region of Ilocos, a major political bulwark of the Philippines’ Marcos dynasty, featuring an image of its signature wind turbines, offers the narrative not just a sense of place but a significant historical layer, though from the get-go Robinson is already clear about such larger historical resonances — the specters of colonialism and imperialism, for instance — opening the film with a maxim from Filipino national hero José Rizal; stripped of this text, the assertion still stands via some haunting imagery scattered throughout.)

As Yolanda spends more time outside and starts to come home late, she harbors questions of death and of divinity existing somewhere else, past the decaying walls of the convent. (The film projects the interiors, supposed sites of rest and relief, as more alienating than the verdant, expansive exteriors.) “Isn’t complete death what gives any of this life meaning?” Yolanda contemplates. At one point, the search for clarity takes her to the stretch of farmland where she and her grandmother used to live, now tended by their old neighbor Diwa (Filipino National Artist for Film Kidlat Tahimik, in a rather surprising appearance). This sequence, to this writer, registers as a brighter dream within a darker one due to the subsequent, slow-moving montage of a possible remembered past succeeded by a shot of Yolanda resting on a hill of gravel, as a passerby approaches to scan her.

What emerges most strikingly in First Light is the breathtaking poise and precision with which Robinson shoots the countryside, which feels thoroughly lived-in instead of touristy. Working with cinematographer Amy Dellar, the filmmaker displays his penchant for positioning the camera at an observant distance, so that the characters are dwarfed in the composition and become part of his becalmed, muted aesthetic, steep in sky and storm blue. In the film, the misty hills can convey suspense and the casual offering of an American-branded sparkling water can feel so passive-aggressive. Every interior shot of the convent, in moments of power cuts, can evoke the danger of an undiscovered cave, bats and rainwater trickling from the ceiling and all. The camerawork, at the same time, flirts with geometries — lines of towering trees giving a frame a sense of scale or an interior shot using curved architectural design to mirror the shape of the human eye, as it simultaneously shows two different floor levels of the local hospital.

While some critics keenly point out how the director’s work as an editorial photographer for the likes of Vogue and Wonderland serves as a major influence in his shot-making, our focus here should be less on his photographic sensibilities and more on his cinematic ones — and his ability to activate all elements of the moving image. Yet, Robinson offers a compelling compromise: the latter is on full display here, without ever betraying the strengths of the former. Perhaps to argue that he isn’t one to abandon his roots, which is evident in the way his long takes so gently commune with the land and so poetically capture entire histories and the marginalia of life, redolent of The Wind Will Carry Us by Abbas Kiarostami, whom the director cites as a formative figure.

In rare gestures of a medium close-up the filmmaker offers his protagonist, we absorb Yolanda’s declining sense of spiritual duty through the sheer power of Ruiz’s emotive visage and cogent take on the character, and the film is a lot better for it. The lack of a proper closure to the case leaves Yolanda far more jaded than she already is, just as Robinson leaves us hanging, though not stuck so much as profoundly changed by the ensuing inaction. There are no miracles waiting to happen here.

For the rest of the townsfolk, life simply resumes, assimilating into the ways of the community for self-preservation. Save for Sister Arlene, who seems to be the only character here who sees through the faux placidity draping over the colonial, subtly violent village. Somehow, she moves on unscathed from the jadedness and indifference, finally committing to a real, and perhaps more divine, calling elsewhere. Rarely has a directorial debut looked as stately and confidently composed as First Light. — LÉ BALTAR

The Misconceived

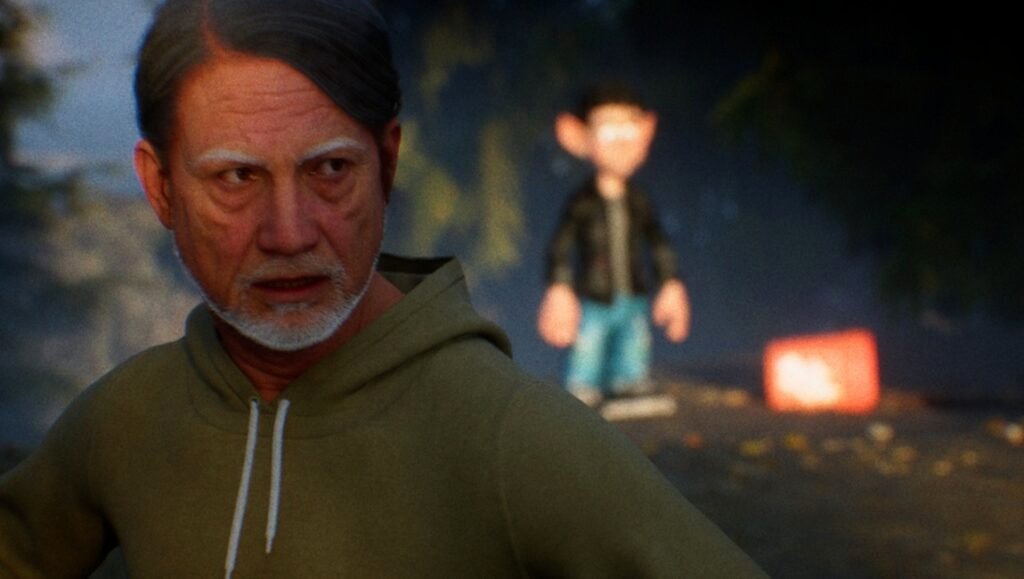

Inside a brightly lit Dunkin’ Donuts, Tyler, a construction worker, meets another, Widgey, who is about to hire him for a home renovation job. Tyler is a single dad handling primary child care. He needs the job. Widgey assures him, disingenuously, that the pay is weekly. The music accompanying the scene punches through The Misconceived’s last title card like the Kool-Aid man, brash and manufactured, corporately optimistic; the kind of tune you’d hear watching a pharmaceutical giant’s onboarding video for new hires. The cheery musical confection colliding with the sigh of working life creates a tonal purgatory, sending the whole scene into the uncanny valley. No surprise, as director James N. Kienitz Wilkins culled the song, along with the rest of the film’s score, from Pond5, a royalty-free music platform. Similarly, the 3D-animated world in which this Dunkin Donuts resides was built in Unreal Engine, an open source video game software, and its winking rolodex of name-brand imagery — Dunkin’ included — pulled from digital image marketplaces. The characters, too, are animated, their movements translated from real-life actors into this rendered universe through motion capture technology and matched to pre-recorded voice performances.

Most of the characters are unmistakably human, but, as with the music, their renderings are just a few degrees shy of reality. Mouths lack the musculature necessary to match the words they speak, and hands never seem to fully grasp objects. Physics in general function according to a mysterious set of rules. Those characters that Kienitz Wilkins deems caricatures, however, like Tyler’s Gen-Z coworker Mikey, are simply cartoons; in this case, resembling something like the demonic sibling to the Rice Krispies mascots, Snap, Crackle, and Pop — you’re surprised he’s not named Squirt, such is the manner in which a stream of crass, anti-woke provocations escape from his rudimentarily rendered mouth.

Kienitz Wilkins’ brand of satire frames Tyler as a provocation all his own. His jaded detachment from careerist impulses frustrate and intrigue the people around him, and his unadorned sense of self affords him no delusions that he’s just one lucky break away from a successful career in filmmaking. One day he explains to an incredulous Tobin — a fame-obsessed sculptor, as well as Tyler’s former college roommate and new boss — his lack of follow-through on his long-gestating screenplay. It’s here when the content of the film and its means of creation force the viewer to consider the tools at a working artist’s disposal and the socio-economic conditions that make it nearly impossible to survive as one. Framed as he is in the story as an artist at heart but construction worker by trade, and positioned between the working class crew and creative class bosses, Tyler’s very existence threatens the already fragile social order. When money and drugs go missing from the house, and suspicions and blame fly left and right, it’s no surprise that the long-fermenting, interclass resentments amongst the characters begin to fizzle and burst.

As was the case with its spiritual predecessor, The Plagiarists (2019), in which Kienitz Wilkins turned digital editing and awkward social interactions into dialectical exercises, The Misconceived‘s obvious accoutrements — 3D animation, motion capture, stock music — obscure the more nuanced trickery simmering underneath their surfaces. For those familiar with his body of work, finally being let in on every secret Kienitz Wilkins has kept up his sleeve over the course of the film prompts not only an emotional release, but feels like an intellectual triumph.

This strategy of withholding in The Misconceived might have come across as alienating if it weren’t for the fact that it’s a wildly entertaining film. One wonders why this single location film with a small ensemble couldn’t have worked as a live-action chamber piece with A- and B-list stars; no doubt Kienitz Wilkins himself has wondered the same thing. And that is part of the reason The Misconceived works so well. Whether the film itself is, as suggested in press materials, “an argument for and against its right to exist,” is neither here nor there. It does exist, and by virtue of a number of legitimizing factors Kienitz Wilkins’ films have not enjoyed: a prominent festival premiere, a PR firm handling publicity, and a sales agent negotiating distribution deals. Perhaps Kienitz Wilkins sits somewhere between the careerist Tobin, foaming at the mouth for a placement in the upcoming Whitney Biennial by a 21-year old curator for whom he barely contains his resentment, and the half-defeated Tyler, a true artist because, as the same curator remarks, he just sounds like one. One imagines such a position is uncomfortable, stress-inducing, and financially unreliable. It’s too bad that’s where great art often finds its home. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

First Days

Kim Allamand and Michael Karrer’s new film First Days begins with a brief opening text, which reads in part, “in your first days after death you must enter a house where no words remain… you wander into the light, only to be left behind… the house is never empty and the waiting never ends.” This is the only context provided for what follows, a plotless 60-minute sorta-narrative that features no spoken dialogue. One might call it a tone poem. A brief, black-and-white prologue begins with undulating waves of light, a swirling morass of opaque textures that slowly coalesce into a recognizable image — a woman’s arm, then a face.

The film cuts to color, as the woman (Nasheeka Nedsreal) awakens and begins traversing a path through a pitch-black forest with only a torch to light her way. It’s a quiet journey, eerie but not quite threatening. The camera is low to the ground, pointing up at the treeline, flickers from the torch illuminating the edges of the space. She comes upon an empty house, enters, and begins to explore its various rooms. All is calm and still, darkness eventually giving way to sun-dappled light. Soon, another woman, Jia-Yu Corti, arrives at the door and joins Nasheeka inside the home. The two spend an indeterminate amount of time together, going about various tasks in silence, before the film ends in another black-and-white sequence featuring a return to abstracted, monochrome images.

Given the presence of the opening text, it’s impossible to read the film as anything other than two recently deceased souls occupying a purgatorial space before eventually moving on to some sort of afterlife. But what’s most intoxicating about First Days is not any metaphysical mumbo-jumbo or spiritualized navel-gazing, but its fascination with the mundane and the material, the corporeal quality of this place-out-of-time. Photographed by Fabian Kimoto on what appears to be 16mm film, with a droning, unintrusive score by Peter Bräker, Allamand and Karrer conjure a wonderfully plaintive vision of moving through our world. The colors are soft but saturated, the light diffuse, the greens and browns of the surrounding wooded area lovingly captured in fine detail. Nasheeka and Corti, meanwhile, stay in close proximity throughout, tethered together by their shared experience despite never exchanging words.

Critics often disagree about how much narrative should or should not be present in otherwise experimental films; Tone Glow and InRO contributor Alex Fields, writing about Rhayne Vermette’s Levers, suggests that “we’re invited to make meaning of what little we can see in this darkened world, but not to consider meaning as something settled or determined.” With First Days, the filmmakers suggest a number of potential quasi-narratives: the actresses are both women of color, and their wanderings around the house are filmed in such a way that one half expects a ghost or slasher villain to jump out from around a corner. But as they venture outside, the film shifts into an almost documentary-like form, emphasizing the landscape, and the women traversing the grounds with a wagon suggest some (unknown to us, the viewer) purpose.

The title First Days also pairs nicely as an antonym of sorts to Gus Van Sant’s Last Days, another film at least in part about free-form wandering through nature. There are traces here too of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work, as well as the aforementioned Vermette, and if First Days isn’t quite as accomplished as any of these antecedents, it does present a clearly articulated vision of a film form in direct opposition to standardized mainstream entertainments. There’s no need for plot and dialogue and action when you can simply capture the beauty of the world and what it means to fully inhabit it. If we all must shuffle off this mortal coil, here is a wonderful document of what we’re leaving behind. — DANIEL GORMAN

Why hasn’t everything disappeared yet

Bulgarian filmmaker Stefan Kotzev had a more traditional scripted drama in mind for his first feature than what he eventually made. Working in close collaboration with fellow Cologne Academy of Media Arts student Lee Juho, he came up with Why hasn’t everything disappeared yet, a cool, meditative portrait of a lonely art school dropout, Moon Sori (Lee), contending with the persistent memories of his old life in South Korea.

Portraiture is an important motif in Koutzev’s film, and not just because of Sori’s vaguely artistic milieu. His atypical character study aims to illuminate, but not so much that Sori, and the audience with him, will arrive at some answer about how to, for example, tell his parents that he actually dropped out of art school months ago; or how to contend with what seems like unacknowledged trauma from his mandated military service in Korea. The revelation of Koutzev’s film is in just how deeply Sori burrows into himself; all the viewer can do is to try to make sense of him from the outside.

Koutzev perplexes the viewer on a number of occasions with warm, humanistic results. The opening scene is one example. In dramatic close-ups we see a teenage girl and her younger brother riding a bus. They’re speaking Bulgarian — a nod to Koutzev’s native country — but are on their way to somewhere in Germany, until the sister realizes they’re heading in the wrong direction. She calls her mother, who seems worried for her children and mad at their father, and laughs off the mistake. Pulled between two places, they’re not too worried; the boy goes back to drawing in his book while she sticks gummy worms to the bus’s windows.

We never return to the brother and sister. Instead, Koutzev introduces us to Sori, fooling around one evening on his rooftop. He jumps over chairs, looks down to the street. He squirts juice from a pouch at a child below, laughs floating back up to him. Sori sketches the outlines of a bust in his sketchbook, the blank spaces between the crisp lines promising the infinite detail with which Sori might fill them. But those details don’t arrive as one might expect. No longer in art school and aiming for a sense of purpose, Sori seems to float through from one day to the next, subsisting on a combination of social encounters – some with fellow Korean expats, during which the conversation inevitably fixates on memories of their prior military service; another with a young German woman with whom he speaks in German and Korean about memories of home — and solitude; when he’s not skateboarding at night, he’s driving bumper cars at a local fun fair or wandering in the woods surrounding the Cologne airport, along the way making friends with roaming donkeys and climbing a tree.

In Sori, Kotzev and Lee have identified a blank slate onto which they can carve the textures that give contemporary urban life its melancholic character: a distant phone call with his mother, meandering conversations with acquaintances, copious alone time. These don’t add up to a complete portrait of who Sori is, but there is a cumulative effect, culminating at the airport. As he watches the planes come and go, we finally gain some insight into a state of mind constantly searching for something out of reach. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Mickey & Richard

Richard Bernstein is a consummate performer. Better known as Mickey Squires to connoisseurs of gay pornography and erotic photography, fields in which he was one of the most popular models in the early 1980s, Bernstein exuded a rough-hewn, seductive masculinity on camera. The mild-mannered Bernstein, though, has retired Mickey Squires — even calling his persona “dead” — and is now in his 70s and living a quiet life in Palm Springs. Filmmakers Ryan A. White and A.P. Pickle, who previously interviewed Bernstein in their documentary Raw! Uncut! Video! about the fetish porn studio Palm Drive Video, take the schism between the two sides of the man as the subject in their new documentary Mickey & Richard. Their depiction of Bernstein’s reckoning with the legacy of his own iconography as Mickey, and the insecurities and traumas that have affected his life as Richard, is astute and moving. Inventively incorporating archival materials and multiple modes of filming, White and Pickle, by illuminating the life of their subject, raise pertinent questions on the effects of maintaining boundaries between one’s performed identity and private experience.

White and Pickle shoot much of Mickey & Richard on a handheld 16mm camera, lending a grainy, textured aesthetic to shots of Richard lounging by his pool and staged scenes of an anonymous man reaching into his shorts while scrolling through photos and footage of Mickey Squires. This makes a pleasing contrast with the extensive archival footage they use, largely but not exclusively drawn from the films Richard appeared in as Mickey Squires, much of which feature bold colors and bright lighting. The usage of black-and-white 16mm film also lends a nostalgic, home video-esque atmosphere to the contemporary footage of Richard — an intriguing counterpoint to the more typical usage of older technologies to mark events as occurring in the past — yet White and Pickle add an additional, complicating layer to this photographic strategy. At many points in the film, White shoots Bernstein digitally, while also capturing Pickle shooting him on film. In a movie so attuned to the multiple layers of identity and presentation, this is a sharp meta-cinematic gesture, signaling the White and Pickle’s awareness of their own role in crafting an image of their subject through their filmmaking decisions.

Clever as White and Pickle’s cinematic techniques are, they do not overshadow the core narrative of their film, which is that of how Bernstein became Mickey Squires, and how this persona affected his personal life during his career’s peak and in the decades afterward. Bernstein, who is candid and charming in his interviews, relates how he identified with Cinderella as a child, having felt out of place within his family and at school. He came out in college, developed a muscular physique, and moved to San Francisco in time to participate in the city’s gay scene at its pinnacle. After moving to Los Angeles, he would gain work as a model for Colt Studios, one of the premier gay pornography studios. As if he were in his own version of A Star is Born, the studio gave Richard a name, a style, and a persona, which he performed with aplomb.

Despite being in-demand as both a model and an escort for much of the decade, Richard believes that his prominence as Mickey Squires in gay circles isolated him. In contrast to the group of close friends he describes having when he was a newly-out college graduate in San Francisco, the obligation for Richard to perform as Mickey in his social life, as well as his professional life, may have isolated him over time. The most affecting, reflective stretch of the film occurs in the aftermath of Richard’s success as Mickey; personal struggles including decreasing professional opportunities, the death of his lover from AIDS, and his own HIV diagnosis several years later only intensified Richard’s sense of isolation as himself, separate from his Mickey persona.

White and Pickle pay homage to Bernstein’s legacy as Mickey Squires without waxing nostalgic; his talent and influence as a model do not overshadow the complexities his work as Mickey introduced into his personal life. Rather, the emotional core of the film lies in how Richard reconciles the two parts of his life: scenes of Richard participating in new photoshoots as Mickey, despite his professed insecurities about his body as he has aged, and a realization that he has meaningful relationships with people who care for him only as Richard, are affecting and sensitively filmed. Much like its multifaceted subject, Mickey & Richard ultimately reveals itself as a film that is aesthetically appealing, intellectually savvy, and emotionally capacious. — ROBERT STINNER

Tell Me What You Feel

It’s low on the list of 21st century horrors, but there’s something uniquely off-putting about watching a self-recorded video of someone crying. It’s tough to say how it became a phenomenon — maybe our increasing isolation demands new avenues for empathy, maybe prefab vulnerability fit itself snugly into The Algorithm — but at the consumer level, self-taped sob fests tend to feel like a consciously curated pile of dirty laundry. The tensions authenticity faces while stretched between poles of practice and performance wind their way through Tell Me What You Feel. Łukasz Ronduda’s movie sits uncomfortably in a gulf between art and artist, therapy-speak and catharsis; it hitches overbearing sincerity as a third wheel to young love.

Patryk (Jan Sałasiński) is a bleach-blond and boney artist from the Polish countryside who haggles with junk-shop owners to hang his creations on their walls. Dejected and with an unsold painting in hand, he ambles past a shop called Skup, which he discovers to be a “Tear Dealer:” an art installation in which folks can sell their tears in the way college kids might donate plasma for beer money. Naturally, most of Skup’s clientele is poor. Class dichotomy may not have been the Tear Dealer’s intention, but under the helm of lead artist Maria (Izabella Dudziak), a rich girl from the city, it’s certainly a byproduct.

Still, Patryk is charmed enough to pursue Maria, and he quickly learns that her performative vulnerability is less a concept for an installation than a lifestyle. Their first date is among Maria’s circle of fellow wealthy artists — including her soon-to-be-ex–boyfriend — who’ve quite literally turned radical empathy into a game. They pass around a bag of prying prompts and questions (Where do you carry your tensions and sadness? What’s your biggest insecurity in bed?) like a spliff and expect one another to answer without hesitation. It makes for a heavy meet-cute. In a prompt that demands Patryk and Maria swap roles, Maria-as-Patryk declares herself “a sad boy… setting up quite the trap for one poor girl;” Patryk-as-Maria admits that the Tear Dealer project is “classist therapy for the poor.” It’s an exercise that casts a long shadow across their relationship.

It’s easy to frame a therapized life as a privilege — or, less generously, the indulgent runoff from a life of nepotistic navel-gazing. Maria’s art and philosophy are the kind that seem tailored to give a boomer raised on Norman Rockwell paintings a conniption (a thesis proven when they eventually collide with Patryk’s working-class parents). Still, there’s an earnestness that betrays the posturing of her projects, and it doubles to posit Tell Me What You Feel as a slyly sweet romcom. As easy as it is to cringe at Maria’s high-concept swings at postmodern self-acceptance (let’s piss ourselves in public and declare we’re not ashamed), Ronduda renders a relationship otherwise defined by the giddiness of puppy love. Patryk and Maria carry themselves with the unburdened aperture of having your whole life ahead of you; their enthusiasm is infectious enough to make you wonder whether you should try your hand at the occasional flash-mob therapy, too.

Especially against Maria’s moneyed instillations, Patryk — whose character and art are loosely based on Polish artist Patryk Różycki — draws with frenetic and scattershot impulsivity; he’s more likely to paint on the back of a popcorn box than a formal canvas. But in the modern art world, his pop-forward tendencies read drolly traditional. “Why are these images so literal?” a prospective gallerist asks him. It’s a criticism that points a few fingers back at Tell Me What You Feel’s own form. Patryck and Maria’s sweetness can sometimes topple toward saccharine, a tendency buoyed by the movie’s gauzy and vibe-forward needle drops. It’s not quite enough to hobble the movie’s critiques toward therapized art projects or the sincerity of Patryk and Maria’s relationship, but it’s easy to wish that Rodunda followed the restraint — or maybe even the cutthroat bravado — of the artists he depicts instead of the indiepop twee that runs renegade of its own expiration date.

Patryk takes a minute to answer the gallerist’s challenge. “I wanted it to be something my parents could understand,” he eventually replies. Of course, people like Patryk’s parents — who couldn’t afford to take Patryk’s late sister to the doctor — don’t frequent galleries in the city. Young love rarely survives for more than a year or two on equal footing, but the class divide and pursuant divergences of wellbeing bear a chasm across which Patryk and Maria can’t seem to cross without falling. Counter to his indie-friendly concessions, Ronduda handles this with remarkable nuance. Patryk and Maria skate across rivers of subtext until the ice cracks, and even then, remain defiant toward devolving into an art school Jack and Rose. Their relationship, doomed as it is, is handled with enough care to elevate Tell Me What You Feel from what might have been a disposable indie romance to something closer to The Worst Person in the World and the better works of Joe Swanberg. It’s sweet and specific and disarmingly curious, a movie that will follow you through every installation of the next eyeroll-inducing art exhibit you find yourself suffering through. — CHRISTIAN CRAIG

A Weapon In My Heart

Jonathan Rosenbaum included an anecdote on Paul Schrader when writing about the revival of Robert Bresson’s first feature, Les Affaires Publiques (1934). As always, Schrader apparently prattled on and on about Bresson’s transcendentalism before the screening began, and the film turned out to be in stark contrast to his highfalutin philosophizing. In order to not eat their words, certain auteurists approach these early and unreleased works with much trepidation and reverence, proclaiming any of the said auteur’s works to be valuable, as they scour the early films for the elusive aesthetic easter eggs that connect these works to the style the auteur is renowned for. Knee-jerk dismissals of these early works (and even later works) a la Schrader are far more common, tying the auteur’s value solely to discerned style. This is especially the case if a director has dabbled in blatant for-hire projects or disreputable genres, because the production can be easily used as a scapegoat. While I do not subscribe to either of the vulgar auteurist strains, there still is a kernel of truth to either of their claims. Any work by an auteur needn’t be automatically interesting as early developments and dry runs, though the fascination is indeed higher if it is an auteur one loves; nor should films that go against the grain of expectation, aesthetically, financially, or reputationally, be casually dismissed. The positions of these two extremities pose a challenge to both the programmer and the viewer who love the auteur’s work, requiring a willingness to expand ideas about cinema and auteurism while still not elevating the film solely on the basis of the auteur’s reputation despite the irrepressible interest in the work because of the auteur’s involvement.

Fortunately, the programmer behind the V-Cinema section — Japanese films made exclusively for video, primarily dealing with action, softcore, and yakuza films — of this year’s Rotterdam Film Festival, Tom Mes, struck a balance between both positions, by selecting a film each from Aoyama, Kurosawa, and Miike which he, whether right or wrong, deemed were of interest, and not populating the entire section with the works of these auteurs. The elephant in the room, Eureka (2000, which itself is less screened compared to films of his contemporaries), was immediately addressed, with Mes dismissing any similarities to this seemingly forbidding film while insisting on the innovative artistry on display in this work. With a brutally direct alternative title of The Cop, The Bitch, and The Killer, A Weapon in My Heart makes no effort to conceal its seedier origins and genre, but rather, like the artistic forbear of Japanese B-cinema, Seijun Suzuki (whose Branded to Kill Aoyama probably alludes to by making his cop the third best marksman), Aoyama explores the possibilities for experimentation lurking within the confines of the action-thriller genre.

As the alternative title indicates, there is indeed a cop (Kojiro Shimizu), a “bitch” (Alice, played by Mika Aoba, though contrary to the archetype of the title, the film’s most interesting character) and a killer (Taro Suwa), all embroiled in a tussle motivated by professional and personal considerations involving a load of heroin. Aoyama begins in media res, as we are rapidly introduced to Alice and a possible killing through a stop-start series of cuts punctuated by the credits. Aoyama’s approach to action is familiar in its structure to other touchstones of the genre, where the setup laid out is charged with suspense, following the eventual action and establishment of the competing factions, but Aoyama’s uniqueness lies in his kamikaze fragmentation, with cross-cuts to shooting practice and shoot-outs doubling as match cuts, overlaid with the cheap gun-and-kick sound effects. By plunging whole-heartedly into the luridness of his premise, not only through the flashy red-lipstick on Alice, but also in the distorted, deep voice of Alice and the killer’s boss, Aoyama pushes it further into experimentation, with the angularity of his shots, the flurry of back-and-forth action, and the pulp premise eventually forming the shards of Alice’s action-fever dream, sliced by both her perspective and that of the cop and killer. This surreal sequence, however dazzling in its form, also hints at the emotional struggles undergirding the character actions, which Aoyama develops by taking a brief interlude from the action after the collision of the three main characters.

Throughout the film, secondary characters almost display a zen-like acceptance of death after it is clear that their struggles are futile, which Aoyama weights beautifully with a pause before the eventual gunshot. As much as I resisted the pitfalls of falling into the auteurist trap of the reverent kind when observing these deaths, the connections to Aoyama’s more known later films are keenly felt in the interlude where Alice, the cop, and the killer let the melancholy behind the action seep in as they reflect on their decisions. Tracking shots and expansions of space initially used to set the stage for action transform into traumatic presences emerging from the aftermath of their actions, and if Eureka had undercurrents of violence lingering in the overt trauma of his characters, this film almost works in reverse, with the melancholy underlying their propulsive actions. Perhaps I have fallen for the same trap as the auteurists I criticized in the first paragraph, but this is not without acknowledging the differences that make A Weapon in My Heart a unique object that could easily reframe the way I looked at Eureka if I had seen the former film first. My auteurist sympathies might have skewered my viewing and responses to the film, but seeing films like A Weapon in My Heart that do not fit into pre-conditioned moulds allows one to expand their notions on auteurism and cinema. — ANAND SUDHA

Comments are closed.