Wyrm suffers from an imbalance between its two halves, but is otherwise emotionally astute and earns the surreal world it conjures with careful, deeply considered world-building.

Expanding on the short film of the same name, Christopher Winterbauer’s Wyrm tells the story of a kid who is very aware of how quickly he is falling behind his peers. Wyrm (Theo Taplitz) is about to fail his Level One sexuality requirement — kissing — and be held back a grade, unlike his twin sister Myrcella (Azure Brandi), whose recent trip to third base has marked her as well on her way to womanhood. The pair’s shared life begins to diverge, fractured by the absence of their parents, the death of their older brother Dylan (Lukas Gage), and wildly different social circumstances.

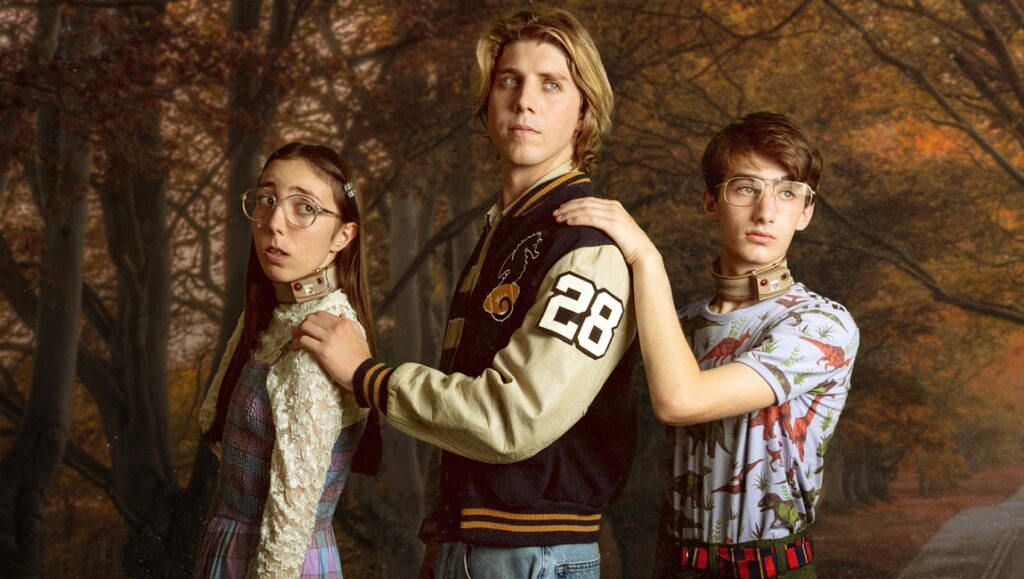

The world may be a gonzo version of our own, where a “No Child Left Alone” policy ensures that romantic/sexual milestones are met as a matter of policy, but all the emotional beats — losing friends, feeling out of place, learning truths about adulthood — tick all the expected boxes of a coming-of-age story. Where the film excels is in embracing its weirder, more surreal sketchings, particularly in the smaller details of its setting: Winterbauer draws a world with science-fiction elements that are deeply considered, its genre quirkiness never feeling gimmicky or over-the-top. His outlandish concepts are supported by an underlying emotional honesty that bolsters the film’s idiosyncrasies instead of allowing them to fall into the realm of pointless satirical whimsicality — the director earns his odd dystopia rather than allowing Wyrm to be carried on the back of a few sci-fi concepts. Equally weird is the film’s fantastic casting — it manages to pull off something of a reverse-Dear Evan Hansen, and instead of casting adults who look wildly out of place among children, casts actual teenagers who look eerily close to adulthood. Supported by costume design that often infantilizes, full of bright sweaters and braces, the cast of Wyrm look as disjointed and caught between modes of being as they feel. The deadpan performances add another element of discordance which, along with Winterbauer’s quietly bonkers world, establish an undeniable vein of absurdism that envisions a new (and probably accurate) perspective on youth.

But the strength of Wyrm’s conceptual vision and understanding of adolescence as a bizarre liminal space doesn’t quite extend throughout the whole film. Wyrm has a clear split in its narrative, shifting focus at the halfway point from its titular character’s romantic pursuits to his family’s grief for his older brother, and while the emotional climax does mostly work (especially in de-emphasizing romance as an important marker of coming of age), the two halves don’t entirely gel. Brandi particularly stands out in this second half as Wyrm’s twin sister, but this part of the film still feels somewhat weaker and less assured than its rock-solid first act. Still, Wyrm mostly lands on its feet, offering a sincere, surreal take on coming-of-age, even if it stumbles slightly while heading toward the finish line, and marks a solid debut feature from director Winterbauer.

Published as part of Before We Vanish — June 2022.

Comments are closed.