2019 was another faithful year that reminded us that there’s no hope whatsoever for anything: Our political system continues to fail us in a remarkable number of ways, cultural institutions continue to decay from lack of funding and relevancy, and the nearly-decade long rise of continued support for far-right nationalism stretched its hands even further. The damage that has taken place, and will continue to take place, shows a general moral failing on the part of society at large — only signs of things to come within the next decade. There is no reason to believe any amount of art, humor, or goodwill can survive these troubling times. None of the albums on this list will change any of that, or even help to provide substantial solace to those who have been hurt. But like all great art, there exists a needed context that helps to inform evaluation. These works speak specifically to our present because they’ve been cultivated in precisely such moments; their goals and ambitions may differ, and they are united in their inability to bring easy solutions to the world’s problems, but merit shouldn’t be predicated on the capacity to provide these answers. Let’s be honest, none of them can. These albums don’t claim to be anything more than representations of the sociopolitical environments they were conceived in — the only form of authenticity they can reasonably claim. Rather, they are a testament to the ambitions and achievements of those working within the precarious conditions of modern times, and while their powers be limited, their functionality isn’t measured by their real world implications. The planet continues to go to shit, some people wish to make music about it, and that’s something. Here’s the best albums and songs of 2019. Paul Attard

Honorable Mentions:

All Mirrors: Angel Olson, Brandon Banks: Maxo Kream, Dedication: Carly Rae Jepsen, House of Sugar: Alex G, Jesus is King: Kanye West, Psychodrama: Dave, Resonant Body: Octo Octa, Songs of Our Native Daughters: Our Native Daughters, Wildcard: Miranda Lambert, The WIZRD: Future

10 Songs We Loved:

1. “Not” | Big Thief

2. “Stupid Horse” | 100 Gecs

3. “God Is” | Kanye West

4. “Bright Horses” | Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds

5. “Mixed Personalities” | YNW Melly ft. Kanye West

6. “Uncomfortably Numb” | American Football ft. Hayley Williams

7. “Free Uzi” | Lil Uzi Vert

8. “Lark” | Angel Olson

9. “Fallen Alien” | FKA Twigs

10. “iMi” | Bon Iver

20. Serving as a sort of spiritual sequel to Solange’s 2016 masterpiece A Seat at the Table, When I Get Home is a love letter to the past and future of Houston. “I saw things I imagined,” Solange repeats on the opener, a sage cleanse of a song that beautifully introduces the listener to a world of funky skits and sexy beats. What follows is an outpouring of positive emotions: love, pride, importance, and friendship are the crux of this work. Along with the album, Solange released a half-hour movie — also called When I Get Home — which contains multimedia performances that comprise some of the year’s most striking images (and that are both grounded and otherworldly), absorbing architecture, dance, and design into this project’s aesthetic. All of the moving parts here — of the album and of the film — are individually audacious and beautifully executed. But the combination feels almost epochal as a whole — and obviously, it wouldn’t be the first time a Knowles sister changed the game. The noirish synth sounds in “Down With the Clique” remain some of the most compelling and bizarre noises to feature on a popular artist’s album this year, while the cosmic “Beltway” communicates so much yearning with two simple phrases. Solange’s collaborators tend to have small cameos that are there to add texture: Playboi Carti hops on “Almeda,” a trap song about black identity that’s one of the hardest-hitting bangers of the year. Later on, Gucci Mane duets with Solange on “My Skin My Logo,” a quixotically slow, jazzy track that also features Tyler, the Creator adlibs. Overall, When I Get Home is pop versatility perfected. Across her body of work, Solange has shown considerable evolution — but her latest may be her biggest step yet. She continues to be one of the most exciting musicians and artists working, and a hugely important voice coming out of the Houston cultural revolution. With every new body of work, the possibility of Solange’s future talents and interests multiply. We should follow her anywhere. Tanner Stechnij

19. Hyped by JPEGMafia and his talented friends as a disappointment, All My Heroes Are Cornballs is anything but; in fact, it’s an exciting new direction for the limitless glitch rapper/experimentalist. Recorded in his home studio, the whole record was produced, mixed and mastered by JPEG himself, a huge feat in kaleidoscopic chaos. Every individual element of the album sounds like streams of consciousness in different directions, from the bizarre sound samples and sonic interpolations to the constant barrage of lyrics alternately presented through rap and vocals. There’s a high level of irony throughout the record, like in the laidback guitar track, “Grimy Waifu,” a love song about his gun, and his cover of TLC’s “No Scrubs,” — renamed “BasicBitchTearGas” — which he turns glitchy and morose. It’s a record filled with so many ideas and so much violence, especially in industrial tracks like the interlude JPEGMAFIA TYPE BEAT, a provocation towards critics who reduce his sound via Death Grips comparisons. Cornballs should help to further differentiate JPEG from Death Grips as it’s an album at least partially constructed on frequently beautiful melodious moments. There are stunning strings littered throughout the album and angelic vocals, like the outro of “Free the Frail,” featuring Helena Deland harmonizing with herself. “Thot Tactics” has a spacey synth line and perhaps Peggy’s most accessible and precious hooks. Sometimes he sings from the perspective of a woman, popping up on the album in tracks like the aforementioned “BasicBitchTearGas,”” a bid that further adds to the DIY nature and bizarre range of topics covered throughout the album. And of course, per usual, Peggy remains in strong political form, rapping about the rise of the alt-right and the changing demographics of his fanbase as he gets more famous. As angry, clever and weird as ever, All My Heroes Are Cornballs is a text that promises to unfold and reveal itself with more listens and digging. TS

18. While Kanye West, the rapper and notoriously unrepentant egoist, endeavoring to make a “gospel album” was never an assured prospect, the biggest reason to think he might succeed at it — as we waited, and waited, on another belated release — was the example of his powerful live show this year. The superlative singers of the Sunday Service Choir joined West first for a series of private performances for friends and family and some industry people before eventually taking their act to the public at Coachella, and to churches and stadiums across the country. The pairing not only provided West with a grounded gospel foundation that, in the past, he’s only flirted with, but it also accomplished the seemingly impossible: taking the focus largely off of Kanye himself, a development he genuinely seemed content with. The result of these efforts was, ostensibly, Jesus Is King, an album that bore Kanye’s name and one that, unfortunately, rarely attained the same sense of spiritual selflessness and collectivism that has characterized the Sunday Service shows; instead, it filtered West’s newfound religious fervor through typical narratives of celebrity’s travails and lashings-out against the press. Before the year was out, though, Kanye had one more trick up his sleeve: a disappearing act. Jesus Is Born isn’t a West album at all, but rather it’s a 90-minute showcase for the range of an extraordinarily gifted gospel group, an album that runs the gamut from more traditional prayer (“Revelations 19:1,” “Satan, We’re Gonna Tear Your Kingdom Down”) to sanctified crossover R&B and pop flips (“Weak,” “Lift Up Your Voices”) to full-on, rafter-raising funk (“Sunshine,” “Balm in Gilead”). There are breakout solo vocal performances on this album that are worthy of a James Cleveland recording (“More Than Anything”), percussion that’s harder and sharper than you’ll find in a lot of hip-hop (“Rain”), and — yes — some Kanye interpolations (though not as many as you might think). If this superbly produced and arranged, and beautifully sung, set turns out to be the best to come out of a born-again Kanye, it’s blessings enough. Sam C. Mac

17. A man (bearded, crestfallen) traipses into the woods, where he holes up in a small cabin and writes music about his heartbreak — agonizingly vulnerable, earnest, intimate music, with whispery confessions and guitars so fine and fleeting they could be feelings themselves. Then, the music, his own attempt at catharsis, becomes famous, and the sad man in the cabin becomes a superstar. What’s more amazing is how the man (Justin Vernon) has refused to repeat himself, persistently and indefatigably redefining his aesthetic while retaining the earnestness that makes listeners feel as if each song is specifically for them. The ephemeral For Emma was followed by a more baroque pop opus, Bon Iver, Bon Iver; and then 22, a Million completely obliterated fan expectations of what a Bon Iver album should sound like, with its glitchy, almost sordid sound, still precise and personal but now processed and calibrated instead of captured. i,i is a (mostly) deft commingling of the older folk-pop and the newer electronic anxiety. If it doesn’t feel as audacious as the last three albums, it’s still an emotionally poignant and sonically dexterous endeavor. Vernon’s lyrics are replete with aphorisms and neologisms, his delivery distorting words beyond their normal meaning and his cadences emphasizing unexpected parts of his lines. The actual words and order, the sequence of verbs and nouns, remains alluringly ambiguous, which is why they feel so universal. On “U (Man like),” which features piano by Bruce Hornsby, Vernon sings, in that swoony yet sad falsetto: “With your long arms, try / And just give some time / Presently, it does include my dues / Ain’t your standard premonitions / All this phallic repetition / Boy, you tell yourself a tale or two.” Some songs are simpler — “Marion” and “Holyfields” could be culled from For Emma — and some, like “Naeem,” are deftly layered, a panoply of instruments and manipulated sounds coalescing into something triumphant. It’s Vernon’s most eclectic album: “Sh’Diah,” culminates in the cry of a forlorn horn, desperate for someone to listen to its lament, while “Jelmore” features synths that recall classic SNES games, while Vernon sings about penury and inequality. Vernon writes about heartbreak and loneliness in a way that never loses sight of hope and never lapses into self-pity. For all its solo rumination, though, i,i is also Vernon’s most collaborative album. On opening track “iMi,” Vernon’s voice, comforting and familiar in its solitude, is joined by Mike Noyce and Velvet Negroni and Camilla Staveley-Taylor and James Blake. It is in a gathering of voices that the album finds hope; the chorus, harking back to Sylvia Plath, goes, “I am, I am, I am.” And he is. Greg Cwik

16. The Highwomen were convened to address a particular problem: Gender disparity on country radio (thus far in 2019, only one woman has had a #1 single). Amanda Shires had the idea of putting together a posse of righteous singers and songwriters with the intention of celebrating women’s voices and airing the kinds of stories the country charts have historically failed to honor. She enlisted Brandi Carlile, songslinger Natalie Hemby, and Maren Morris; together they made a self-titled record with Dave Cobb in the producer’s seat, plus supple support from the likes of Jason Isbell, Sheryl Crow, and Yola. You can hear their problem-solving pragmatism in full effect on the opening title song, walk-on music that rewrites the famous Highwaymen anthem, a tale of masculine derring-do, into a whispered history of all the women who’ve been blotted from the public record. The group triangulates their politics on “Redesigning Women,” a funny and harmony-rich ode to ladies who contain multitudes, as well as “Crowded Table,” a soft-touch anthem of inclusion and hospitality. But the triumph of The Highwomen is that it’s as eager to show as to tell; many of its songs live at the margins of gender politics, and speak to everyday experience from a place of candor and cheerful humor. The joke quotient is highest on “Don’t Call Me,” a gleefully trashy song of dismissal from Shires; subtler but no less clever is “Loose Change,” a Morris number that bares sharp fangs beneath its plainspoken country cliches. In addition to being very funny, the record is also grounded in country tradition, eschewing contemporary polish in favor of spare honky-tonk, Western swing, and outlaw austerity. Its crisp formalism makes the little tweaks and adjustments all the more savory, as on “If She Ever Leaves Me,” a classic country infidelity song about a guy who’s cluelessly trying to pick up a lesbian, voiced with wry understatement by Carlile. Also noteworthy are “My Only Child,” a bittersweet tearjerker written with spirit-Highwoman Miranda Lambert, and “My Name Can’t Be Mama,” about how identity is complicated and nobody is ever just one thing — an assertion The Highwomen makes again and again, pointedly, humorously, and elegantly. Josh Hurst

15. Allison Moorer’s last album, Down to Believing, which drilled into the messy cycle of grief, was arguably a career-best for the extraordinary singer-songwriter. Her latest, Blood, plumbs even greater depths and boasts even more scalpel-sharp songwriting; in what has been an exceptional year for country music, it’s handily the album of the year. The album isn’t simply “about” the well-known story of her parents’ murder-suicide, which has intermittently bubbled up to the surface over the course of her career. Instead, Blood uses that autobiographical horror as a starting point, as Moorer wrestles with such heady topics as generational cycles of grief (on the stunning “Nightlight” and the title track) and the debilitating effects of long-term abuse (raucous lead single, “The Rock and the Hill”). What’s most striking about the album is the complexity of Moorer’s emotional palette: There isn’t outright forgiveness for her father, but there’s a stunning sense of grace in her attempts to understand him better. She avoids the temptation to paint him simply as a villain in a tragic narrative and, instead, captures the humanity in all four members of her family. The album’s release is accompanied by a release of a memoir of the same title. The book goes into greater detail — and, though her insightful blog had already proven it, demonstrates the power of Moorer’s prose — but Blood stands fully on its own as an album of rare power and depth. Jonathan Keefe

14. In order to confront the ever-growing postmodern fears that come with living in the contemporary world, Natalie Mering, aka Weyes Blood, went to a new place — a place between helplessness and hope, one where even an ocean liner can rise from the sea more than a century after it sank. The sound of this specific state of being is, appropriately, just as revisionist and stylized: Titanic Rising is an amalgamation of the pop-rock of Mering’s parents’ generation and the of the sensibilities of a modern singer-songwriter, one who happens to have a taste for avant-garde composition. And then there’s buzzed-about single and album centerpiece “Movies,” which highlights Mering’s futurism with a scalar, Tron-esque synth pitted against the singer’s alto vocal, and which laments a need to regain agency. “A Lot’s Going to Change” and “Something to Believe” both provide a contrast; they’re not without their quirky licks and instrumentation choices, but they put the focus on Mering’s Joni Mitchell-esque vocal, and on the evocatively romantic sounds of folk music’s past. With one foot planted in tradition and one in the ever-evolving present, Titanic Rising side-steps the pervasive gloominess of everyday life, but not in a hackneyed ‘Yes, We Can’ way common in centrist liberal politics. While facing global fears, Mering turns inward and becomes honest with her seemingly interpersonal issues. In “Wild Time,” she sings about a dissolved relationship, offering her partner solace from the damage that’s been caused: “Love, pain, loving you / Everyone knows you just did what you had to.” She forgives this partner between lines about devastating climate change and industries collapsing, before finally reaching a natural conclusion: “It’s a wild time to be alive.” Mering works further through her lost love on “Picture Me Better,” a deceptively intimate ballad that’s heavily orchestrated, with reverb-drenched guitars, lush wind instruments, and beautiful choral arrangements. “It’s tough / Since you left, I’ve grown so much,” Mering croons, reminiscing over fond memories and reflecting on hard-learned lessons. In a truly symphonic style, Titanic Rising closes with a summarizing coda: “Nearer to Thee,” named after the fabled hymn often associated with the Titanic’s string ensemble’s final bow. It’s only here when it becomes clear what kind of trick Weyes Blood has pulled off; she’s enraptured her listener with a beautiful soundscape, level-headed and understanding lyrics, and a silky voice, but her album is, of course, about total destruction. The idea of the Titanic returning from the deep takes on a much different meaning when Mering eulogizes rising tides and a generation stuck in a cycle of nostalgia. Titanic Rising is an album full of contradictions, but it also seems to offer a prescription for contemporary life: fix yourself before everything around us goes to hell. TS

13. FKA Twigs’ Magdalene burst forth from the body of her previous work, these plastic-y future dance tracks, so much of what she has sculpted strategically pared away. In some ways, Magdalene feels like a disruption of the FKA Twigs project, but in many ways its a practical and rewarding progression, one that finds Twigs reimagining the theses that have guided her career thus far. Over the course of her last three projects, Twigs used pop music textures and parallel dance choreography as a means of forging a visible, public persona, while addressing the precarity of laying claim to such an image. Magdalene finds Twigs continuing to live within our gaze — her livelihood dependent on our attention — but this time the tension between her and us is not so explicitly centered around sexuality, but rather the aftermath of love and intimacy. Magdalene isn’t so much a sonic departure for Twigs, but a tonal one, which proves to be a sharply clever approach to such material. In this way, Twigs suggests our consumption of art and celebrity stems from a single source, objectification as a distinct purpose. An R&B sex ballad can just as easily be reimagined as a document of despair and self-destruction, and the same goes for the sort of depressive trap that Twigs so ably navigates here (with a fitting assist from Future, a pop icon who knows a thing or two about making melancholy bangers). In this way, Magdalene gets to expose the shortcomings of its medium and context, while determining new ways of rendering meaning from it. M.G. Mailloux

12. Jamila Woods’s Legacy! Legacy! embodies the excellence of a person of color — not just the presence of excellence, but also its range. The many names that are alluded to by this album’s songs’ titles — Betty Davis, Frida Kahlo, Octavia Butler, and lots of others — each introduce different modes of creative expression, but also the different facets of talent and inspiration that manifested in these individuals’ work. The electric-guitar riffs of “Muddy” allow Woods a moment to rage; the slick jazz licks of “Miles” become a flex; and “Frida” offers a rare moment of vulnerability on an otherwise assuredly self-confident album. The record’s smooth neo-soul acts as a mask of cool stoicism that she must wear lest she cause misunderstanding; you hear the range of influences spilling from underneath but only in considered measures, as if Woods is careful about how much she shares. There’s also a sense of pressure gleaned from the way Woods allows the icons she’s gesturing toward to provide a foundation for her work, even as they also stress their impossible-to-meet standards. How can one exactly adopt the resilience against bigotry heard in “Zora,” or the fearlessness needed to forge an uncharted path like “Octavia”? Woods searches for her own answer on Legacy! Legacy! — learning from the greats, while ultimately trying to stake out her own definition of excellence. Ryo Miyauchi

11. Panda Bear’s Buoys; or, Panda Bear Meets the Grim Reaper (which would have been a more appropriate title, if only he hadn’t decided to use it for his previous album). Nearly a decade since AnCo’s critical darling bemoaned the material possessions required to support his family — whilst jamming with his three best friends from Baltimore and cashing in his record-high Pitchfork clout — Noah Lennox has gotten old. He didn’t even appear on his band’s latest release, instead choosing to focus on his own (much better) music and not waste the overseas flight. It’s a sense of distance — from his friends, family, past, and his fleeting youth — that serves as the foundation for his fourth studio album, but one that never loses sight of the singer-songwriter’s greatest strengths: his impeccable sense of melody and desire to funnel emotional vulnerability through the most seemingly banal of expressive lyrics. While Panda’s previous three solo outings practically drowned out his Brian Wilson-esque vocals under a lush palate of layered instrumentation, most tracks on Buoys are stripped to their most basic sonic elements. Take “Cranked,” which employs a simple acoustic guitar riff, adds some textured vocal samples, uses a few droning, lo-fi synthesizers that are almost consumed by a series of spacious delays, and sounds just as psychedelically creative as anything the forlorned quadragenarian has previously produced. While still experimenting with new approaches towards the process of music-making, Lennox’s biggest breakthrough here comes from constructing a project of such raw intuitiveness that still manages to cohesively encapsulate not just his career as a musician, but as a husband and father — one remiss at the uniformity longevity brings (“Can’t remember when / We last lost ourselves”) and one who’s accepting of the hardships of senescence. The ever-elusive Panda described Buoys as the “beginning of something new,” a vague statement that any artist can whip out to draw attention for their next project, yet there’s something not entirely false about the ethos of such an affirmation here. It’s in remembering the past that Lennox is able to move on in the present, charting a course through unknown waters with a newfound maturity. Paul Attard

10. Musicians who rely on either humor or political rage as the foundations of their songwriting typically run out of ways to keep their edge, or to remain relevant, at some point in their careers. Todd Snider, a wiseass who has always been unapologetic with his politics, has somehow managed to get sharper over time. He’s never released even a middling album, but the run he’s been on since 2008’s Peace Queer, as an alt-country troubadour who tees-off on contemporary society, is really without precedent. That Cash Cabin Sessions, Vol. 3 is perhaps his strongest album is both a testament to Snider’s attention to his craft, and to what’s going on in the world today. Some of Snider’s targets are obvious — it will surprise no one that he goes hard after our current sitting president and his administration — but his masterful use of language ensures that the jokes always land, even if they don’t land where they initially seem like they’re going to. “Talking Reality Television Blues” is a piss-take on country music’s recitation sub-genre, with Snider going on a rambling journey through the history of television that accounts for everything from the moon landing and the advent of cable to The Real World and The Apprentice. While it could easily have turned into a “Get Off My Lawn” screed, Snider takes a, ‘Can you believe this shit?‘ stance. That’s also true of this album as a whole; Snider’s wordplay and his affable persona highlight the absurdity of life at this particular and peculiar moment, and without necessarily making light of, or dismissing, the more harmful aspects of it. Snider is no less effective when he dials back the sarcasm: “Force of Nature,” on which Jason Isbell sings high harmony vocals, is a casually empowering look at aging, while “The Ghost of Johnny Cash” allows Snider to pay tribute to an icon. The choice to record at the Cash (as in Johnny) Cabin Studio proves to be the right choice for this collection of songs, with the stripped-down approach putting the focus on what might be Snider’s best-written material. JK

9. Vampire Weekend’s Father of the Bride ennobles all the tiredest cliches about classic “double albums”— how its charm is in its sprawl, how minor songs contextualize major ones, how the discursions reinforce key themes. It also validates the pleasures of pure studio craft as surely as any album from Steely Dan or Fleetwood Mac, offering endless textures and tiny details to get lost in. And it justifies its Bible references, too, as well as its elder-millennial hand-wringing, with a dazed portrait of privilege and malaise. There’s a lot happening on Father of the Bride, and the album rewards whatever investment of time and attention you care to make. JH

8. Listening to Big Thief’s U.F.O.F. is dangerous: it leaves one ensnared, feeling pensive and alone and numb. Few albums in 2019 could transport one into a space where nothing else mattered, where its songs could capture the feeling of isolation and contentment with being in such a state. Lenker’s voice was the skeleton key—her beguiling vocals, reminiscent of those belonging to Josephine Foster and Diane Cluck, carry a mystique that’s felt in every hushed singing and evocative lyric. Opener “Contact” is a slowcore number whose lethargic tempo and queasy timbres construct a dread reminiscent of early Red House Painters. “From” finds a single guitar figure swirling around Lenker’s curlicue melodies as she sings of a pregnancy born of rape. The title, which stands for UFO Friend, points to the transience of relationships and emotions and life: “Let me rest, let me go/See my death become a trail,” sings Lenker in “Terminal Paradise,” singing calmly as if slowly accepting her eventual fate. Still, moments of beauty exist—there are flashes of intimacy, even if short-lived, on “Orange” and “Century.” And in a sense, there’s a beauty that comes in Lenker’s acknowledgement of life’s fleeting nature. When closing track “Magic Mirror” ends with indiscernible looping audio, it feels like a release into the void: she wants us to be content too. Joshua Minsoo Kim

8. Listening to Big Thief’s U.F.O.F. is dangerous: it leaves one ensnared, feeling pensive and alone and numb. Few albums in 2019 could transport one into a space where nothing else mattered, where its songs could capture the feeling of isolation and contentment with being in such a state. Lenker’s voice was the skeleton key—her beguiling vocals, reminiscent of those belonging to Josephine Foster and Diane Cluck, carry a mystique that’s felt in every hushed singing and evocative lyric. Opener “Contact” is a slowcore number whose lethargic tempo and queasy timbres construct a dread reminiscent of early Red House Painters. “From” finds a single guitar figure swirling around Lenker’s curlicue melodies as she sings of a pregnancy born of rape. The title, which stands for UFO Friend, points to the transience of relationships and emotions and life: “Let me rest, let me go/See my death become a trail,” sings Lenker in “Terminal Paradise,” singing calmly as if slowly accepting her eventual fate. Still, moments of beauty exist—there are flashes of intimacy, even if short-lived, on “Orange” and “Century.” And in a sense, there’s a beauty that comes in Lenker’s acknowledgement of life’s fleeting nature. When closing track “Magic Mirror” ends with indiscernible looping audio, it feels like a release into the void: she wants us to be content too. Joshua Minsoo Kim

7. Western Stars is Bruce Springsteen’s strongest record in years, and it also marks a rather significant departure for the Boss; working without the E-Street Band, he is instead cloaked in lush strings (his backing band includes multi-instrumentalist Jon Brion), putting a baroque spin on his romantic melodrama. The American West is his subject, and specifically the West as seen through the lens of Hollywood. Springsteen has always had an interest in cinema, and here that fixation is front and center, aided be the flowery orchestration: “Drive Fast” is sung from the perspective of a battered old Hollywood stuntman; the title track concerns a washed up cowboy actor reminiscing on the time he had the privilege to be shot by John Wayne onscreen. This wistful tone reverberates throughout the entire album, taken up on other tracks that feel more directly of a piece with Springsteen’s POV. On “Hello Sunshine” he wonders whether he’s grown “a little too fond of the blues”: “You know I always loved a lonely town,” he croons, “Those empty streets, no one around / You fall in love with lonely, you end up that way.” The song reads as optimistic on the page, a reclamation of sunshine after a lifetime spent wallowing in “the rain and skies of grey,” but there’s a palpable desperation in Springsteen’s voice as he pleads, “Hello sunshine, won’t you stay?” — suggesting that some of that melancholy still remains. Perhaps the most striking aspect of Western Stars though, is the astonishing warmth of Springsteen’s vocal performance. The famously gravel-voiced 70-year-old has rarely sounded as lovely as he does here, his rich baritone soaring in tandem with the orchestral arrangements. And it’s the way that he sounds at once mournful and at peace that makes these dreamy reflections resonate so strongly. Brendan Nagle

6. It would still be a stretch to call her a household name, but Rhiannon Giddens saw a substantial increase in her public profile during 2019, thanks largely to her roles in Ken Burns’s Country Music documentary series and the wildly popular “Dolly Parton’s America” podcast. But Giddens’s year wasn’t limited to her commentary on others’ work: She’s behind two of the year’s finest albums, both as a collaborator on the Our Native Daughters project and with There Is No Other, made with jazz musician Francesco Turrisi. The latter traces the influences of African and West Asian sounds on what is typically considered Western popular music. Indeed, there’s fascinating ethnomusicology at play in Giddens’s and Turrisi’s purposeful arrangements and choice of instruments. That cultural context is key to the greatness of There Is No Other, but the album is hardly an exclusively academic exercise. What Giddens has already proved over the course of her solo career is that she’s among the finest interpreters of her generation, and her singing throughout this album represents career-best work. Here, she sings the finest version of “Wayfaring Stranger” that this writer has ever heard, and her “Gonna Write Me a Letter” and “I’m on My Way” are no less striking. Ultimately, There Is No Other is both a work of important cultural criticism and a testament to the universal appeal of truly gifted musicians at play. JK

5. Let’s get this out of the way: “Me!” is by every measure a punishable offense. You know what’s death by a thousand cuts? Brendon Urie’s voice, that’s what. The martial drum beat makes for one of the most phoned-in instrumentals in pop this year. The spelling lesson is insulting. Most gallingly, it’s hard to believe that a songwriter as gifted and as smart as Taylor Swift doesn’t know all this — which makes the song cynical, too. Now, get over it; that misstep of a single doesn’t queue up until 50-odd minutes into the most ingratiating, otherwise consistent, pop album blockbuster of 2019. If Lover isn’t Swift’s best album, it’s probably only second to 2012’s Red; it similarly draws strength from diverse sonic influences and from the flex of its sprawl. Having extra space seems to enable Swift to craft smaller statements, songs she’s probably content with not pushing as singles: Dixie Chicks-featuring slow-burn “Soon You’ll Get Better,” or the quirky steel drum-accented “It’s Nice to Have a Friend.” Swift’s last two albums (especially 1989) chained themselves to tunnel-visioned efforts of aesthetic positioning and commercial dominance, which is basically to say that they were singles albums aimed at making Swift the center of the pop zeitgeist. Lover doesn’t sound nearly as burdened by any particular expectations, and yet it casually runs through through some of Swift’s best songs to date: a direct, astute dismantling of sexism, “The Man” knocks like “Style” but with substance, and a sultry, horny (“the altar is my hips”) Taylor croons over smooth jazz saxophone on “False God.” To be fair, Lover does benefit from groundwork laid by Swift’s last two albums: even as the set ping-pongs between various pop genres and idiosyncratic production choices, nothing here feels outside of the artist’s wheelhouse, largely because of the range that Swift has established for herself at this point. In fact, think of Lover as Taylor Swift’s own pop music refinery: she may have already staked her claim on much of the aesthetic elements and lyrical preoccupations that she’s working with here, but this album cultivates them. SCM

4. The glorious triumph that was David Berman’s return to the public eye this past summer took a fast turn towards tragedy when the beloved musician took his own life less than a month after the release of his new album, Purple Mountains. Known primarily as the frontman for esteemed indie rock outfit Silver Jews, Berman’s struggles with addiction and depression have been well-documented. But when he started giving interviews in anticipation of his first new record in a decade, it seemed like things were looking up. “David Berman is Alive and Living in Chicago,” read the headline on a profile for The Ringer, and the celebratory tone of that proclamation is balanced only by the sourness of what followed. This uncomfortable duality characterizes much of the experience of actually listening to Purple Mountains as well; what first seemed a bountiful re-opening of a lost future quickly became a painful and definite close. Reading the album as a goodbye letter (not unlike the way many approached David Bowie’s Blackstar) feels perverse, but it can be hard not to take it as such. “Nights That Won’t Happen” was written in response to the recent death of his mother, but when Berman declares that “the dead know what they’re doing when they leave this world behind,” it’s as if he’s assuring listeners that his “suffering” is finally “done.” Ultimately, however, his intent in writing these songs is not so important; the reason that they resonate so profoundly is because they display the same poetic insight and vulnerability that defines Berman’s career — as time wears on it becomes more and more clear that Purple Mountains is as strong as anything in his catalog. And while revisiting his music can be severely upsetting in the wake of his passing, there remains a genuine comfort in knowing that it will always be here. It’s a feeling summed up beautifully by Berman himself on the gorgeous “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan”: “Songs build little rooms in time / And housed within the song’s design Is the ghost the host has left behind / To greet and sweep the guest inside / Stoke the fire and sing his lines.” BN

3. Ghosteen is an album of hauntings, both in its feet-fully-planted confrontation of unraveling grief and in its shifting depiction of the messy impenetrability and capriciousness of one’s mind under such circumstances. This latest record from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds is emotionally girded by the death of the singer’s son in 2015, his familiar ruminations on mortality underscored by a newfound mistrust in his own ability to cognize experience. Across eleven exorcistic tracks, Cave alternates between exercising faithfulness and lapsing into faithlessness; he is, by turns, re-formed and riven. Ghosteen is an elegy and a prayer, and Cave’s usual, disparate sonic components are here distilled into something more symphonious than before. Spectral harmonies and synthetic textures imbue this album with a sense of perpetuity, each orchestral lament flowing into the next, a piano’s melancholic twinkling establishing melody beneath the whelming, ethereal gauze. The singer’s recognizable and guttural baritone is frequently upset by his abraded falsetto throughout Ghosteen, and both work to enrich the text being orated — establishing Cave’s voice as that of a man warring, in real time, for possession of the self. Familiar Cave imagery abounds: the horse as symbol of utopic, unbridled freedom, but often under threat, and the train as the mechanistic force of inevitable movement toward the future (the most most affecting application of both can be found on album highlight “Bright Horses”). But like all else on Ghosteen, these reference points bear the additional immensity of Cave’s loss. This burden manifests, beautifully, in contradictory ways, even on the same track: “Ghosteen Speaks” imagines a funereal scene as witnessed by the titular Ghosteen, a clear analog for Cave’s son (and, here, a cathartic expression for the singer), who alternately finds comfort (“I think they’re singing to be free / I think my friends have gathered here for me”) while also struggling against cleansing platitudes (“I try to forget to remember that nothing is something / Where something is meant to be”). It’s firmly within this psychological tension that Cave bookends Ghosteen. Album opener, “Spinning Song,” is a dark-inflected fairytale dirge that ends with a sturdy-voiced repetition (“I love you”) before Cave brokenly wails, “Peace will come in time…a time will come for us.” On “Hollywood,” Ghosteen’s 14-minute send-off and a wounded riff on a Buddhist parable of loss, Cave’s voice builds from a controlled bass to trebled crescendo: “It’s a long way to find peace of mind…And I’m just waiting now for my time to come.” Luke Gorham

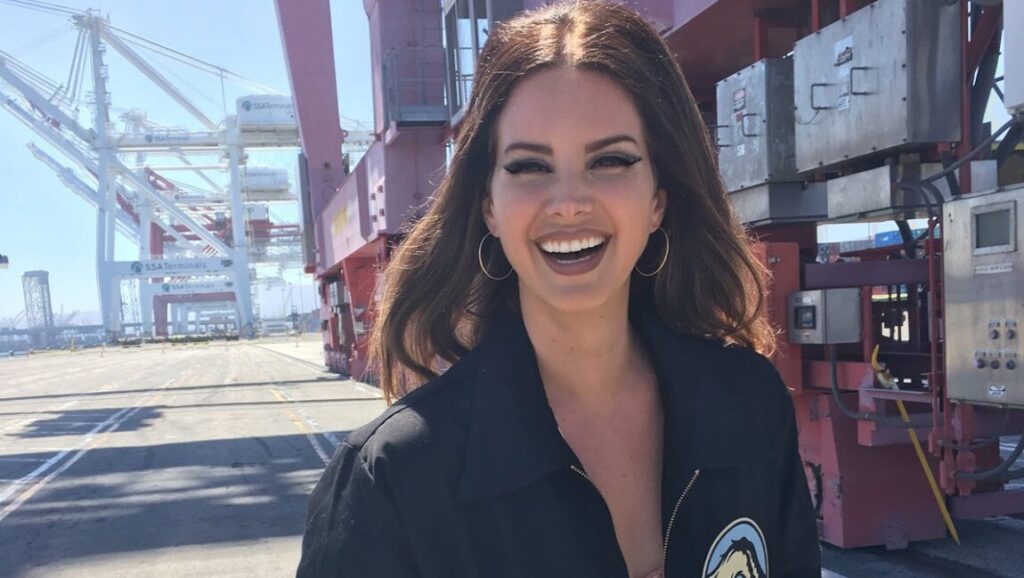

2. Lana Del Rey has always loved putting broken things back together again, and on Norman Fucking Rockwell!, her romance and message of resilience seems addressed to America itself. Collaborating with Pop Midas Jack Antonoff, Lana’s latest is her new peak — as a poet, an intellectual, and a self-aware American. Tapping into the history of her nation, Lana creates a subdued singer-songwriter album that captures our present moment, something akin to Laurel Canyon masterworks by the likes of Joni Mitchell and Carole King. Now, as Lana looks around, she struggles to find rebels and revolutionaries. “Kanye’s blond and gone,” she laments on “The Greatest,” an anthemic eulogy to American culture, seemingly meant to be sung on top of dive bar tables. The album’s title track finds a “man child” poet succumbing to narcissism, boring everyone around him. The situation is bleak: on “California,” a lover — surely some All-American combination of Elvis, Miles Davis, and Father John Misty — has fled the country. Naturally, Lana turns back time to look for genius, finding Sylvia Plath, the Beach Boys, Sublime, and Crosby, Stills and Nash as sources of inspiration. Lana also looks back through her own career, touching an abundance of self-references, and refurbishing “The Next Best American Record,” a track that was originally intended for Lust for Life. The latter move proves especially appropriate — because, by all measures, this is that record. Norman Fucking Rockwell! is art that sounds like it’s coming out of a cultural movement, a new school of thinking and art-making, shared among like-minded individuals that’ll help define the crossroads we’ve found ourselves at as a nation. This is a collection of songs that feel big enough to last forever. In America, there’s a contemporary perception that, when an artist’s personal life is shrouded in their art, it can feel like they’re not giving away enough of themselves. But you can’t say that of Lana. She’s a complicated woman who has dug deep, sacrificing herself as a scapegoat for aesthetics and exposing the flaws inherent in the American psyche. We feel like we don’t know Lana yet only in the sense that there seems to be so much more for her to say, not at all because what she’s said feels phony. A surprise release like “Looking for America,” which was written and recorded a day after the El Paso and Daytona shootings, shows a consistently thoughtful artist who’s still trying to figure out her place in a world where confusion reigns. After all, writing a great story is always personal, and Lana is telling the story of America in real-time. TS

1. 100 Gecs makes music that dares the listener to hide behind snobbery. Every song is designed to make your parents scoff, as if Gecs masterminds Dylan Brady and Laura Les exhumed the corpses of every embarrassing pop music trend of the collective millennial youth and stitched them together into a shrieking, vengeful freak femme Frankenstein. The duo’s 2019 collection of tunes comes with an appropriately high voltage title (1000 Gecs) and comprises 10 tracks in 23 minutes; it’s the punkiest record released, since, like, Yeezus. And as was the case with Mr. West’s opus, 1000 Gecs is an exercise in leaning in to outsized pop persona and bathing in the simulacrum of contemporaneous culture. But whereas West (and just about any and every rapper) luxuriates in self-referentialism, Gecs buries the self amidst their sonic reference points, asserting pop culture curation as personality. This is to say that Gecs are their music; there is no need to delve deeper into who they are, for they have spewed it all out into a digital file. The video for album single “Money Machine” purposefully obscures Brady and Les’s faces via digital effects, and some glam metal-esque (or Willow Smith-esque) hair whipping. Even the album cover only shows the pair’s backs to the camera, the figures leaning towards a bush — like that Homer Simpson gif in reverse. This isn’t a confrontational choice, but an act of solidarity between artist and audience, an invitation to indulge, with them, in everything we were told not to like. Indeed, the Gecs project seems eager to decentralize musical auteurism — but Brady and Les’s music never reads as preachy or condescending. There is no irony here, no smirks; ‘uncoolness’ is a merit, not just a new pose. Gecs borrow the syntax of rap music, while swapping in their own gonzo boasts and threats, a very literal display of the mental processes that allow us to see ourselves in the music of others. One could imagine how this approach might result in tasteless parody. But Gecs are already starting from a place of “tastelessness,” a position that allows them to engage their imagination in daringly dumb ways. One song will sound like Sleigh Bells, before the distorted vocals morph into death metal pig squeals; another will fuse trap, cartoonish Ariel Pink melodies, and Deadmau5-style dubstep. The duo update Reel Big Fish via Fred Figglehorn-sounding vocals and the guitar riff from the song Matt Damon sang in Eurotrip. Each component on 1000 Gecs seems crafted to provoke a wave of queasy recognition that, eventually, blossoms into joy. It’s a compilation of songs that feel like cruising through an iTunes library, in the era of the 99 cent single. Gecs understand that the nostalgia machine is moving faster than ever, and they’re not looking to disrupt it — they’re figuring out how to steer. MGM

Comments are closed.