Rule 34

At its core, the intellectual thesis of Julia Murat’s intelligent if inconclusive film belies a more emotional investment. As its title might imply, Rule 34 denotes both the anarchic signification of the eponymous Internet maxim as well as the ambiguous sexual and social politics that have informed — and in turn been influenced by — said maxim: “If it exists, there is porn of it. No exceptions.” Recently crowned the winner of the Locarno Film Festival’s Golden Leopard, Rule 34 follows closely, artistically speaking, in the footsteps of its predecessors; its quiet tableaux of human faces, reverent framing of bodies, and unflinching dissection of relationships of power find significant resonance in the painterly phantasmagoria of 2019’s Vitalina Varela or in the abject, existential portraits of 2017’s Mrs. Fang. But Rule 34, unlike those works, is also remarkably contemporary. Its subject matter proves more urgent than apparent, and also less explicitly edgy than expected. Rather than train her eye upon the Rule 34 website proper (typically synonymous with graphic and pornographic representations of animated characters), Murat examines the private and public lives of Simone (Sol Miranda), a 23-year-old Brazilian female law student, and showcases their discomfiting parallels with increasing intensity.

Simone studies the law and its application by day, and doubles as a camgirl at night. Her everyday existence is bookended by visits from her fellow students (who are also possibly her casual lovers), video calls with a friend and BDSM practitioner, and streaming sessions via Chaturbate. There’s a comfortable narrative rhythm that Rule 34 quickly settles into, streamlining her political development in tandem with the more personal and physical aspects of her life. Over time, the politics of her day job weigh on her, as she — and those she converses with — begin to raise thorny and deeply insoluble questions about human ethics and agency. While training to enter the service as a public defender, Simone confronts not just the dilemma between sexual prurience and prudence, but also the disjunct between the hypothetical and the actual: before the figures of women (housewives, mostly) abused physically and psychologically by their husbands, the law appears to hold little substantive ground. In light of this inadequacy, she finds herself delving into the darker corners of online discourse, scouring web pages for both sadomasochistic rhetoric and realization.

Here, perhaps, a qualification is necessary: Rule 34, in contrast to Murat’s previous feature Pendular, is structured more conventionally, and the crux of its themes concern well-trod ground on the ethics of spectatorship and consent. There’s something to be said about this accessibility, whose centering of ideas alongside experiences makes for a discussion on gendered violence somewhat familiar to the viewers of Daniel Goldhaber’s Cam or Ninja Thyberg’s Pleasure. But conventions aside, Murat trades the comfort of didacticism for the pleasures of the phenomenological, as empowerment and emaciation overlap in Rule 34 via Simone’s partaking in more and more dangerous games of sexual humiliation. The flesh, here, may be disappointingly tame for the brashly expectant (explicit and therefore authentic text messages, sequences of asphyxiation and domination rendered fluidly sensual, etc.), but the bones will rattle for those attentive enough to visualize and empathize with Simone’s uniquely brittle perspective as human, woman, public servant, and private lover. How should one be political in the age where porn and apoliticism take no exceptions? Though it provides few novel answers, Rule 34 develops its negatives piercingly, and with a glimmer of hope.

Writer: Morris Yang

Fairytale

It’s possible to make the claim that, from a certain point in his career, the works of veteran (and outcast) Russian filmmaker Alexander Sokurov have emplaced the notion of history as their main focal fascination, at least in a more explicit sense. History, in its grander discursive aspects (in terms of the corrupting effects of power, tyrannical decadence, or its socio-political panorama), is vividly present in his Tetralogy of Power (Moloch, Taurus, The Sun, and Faust), in Russian Ark and Francofonia (where the director also exhibits art and culture as the true antitheses and resistant forces against the maladies and tragedies of modern civilization), and even in the more personal realms of Mother and Son, Father and Son, and Alexandra (where the familial contexts both reveal their own small-scaled (hi)stories and are situated within broader narratives). Thus, his most recent film (after seven years), Fairytale, once again invites viewers into this familiar domain, but with fresher artistic vision and aesthetic innovation than what we’ve seen before.

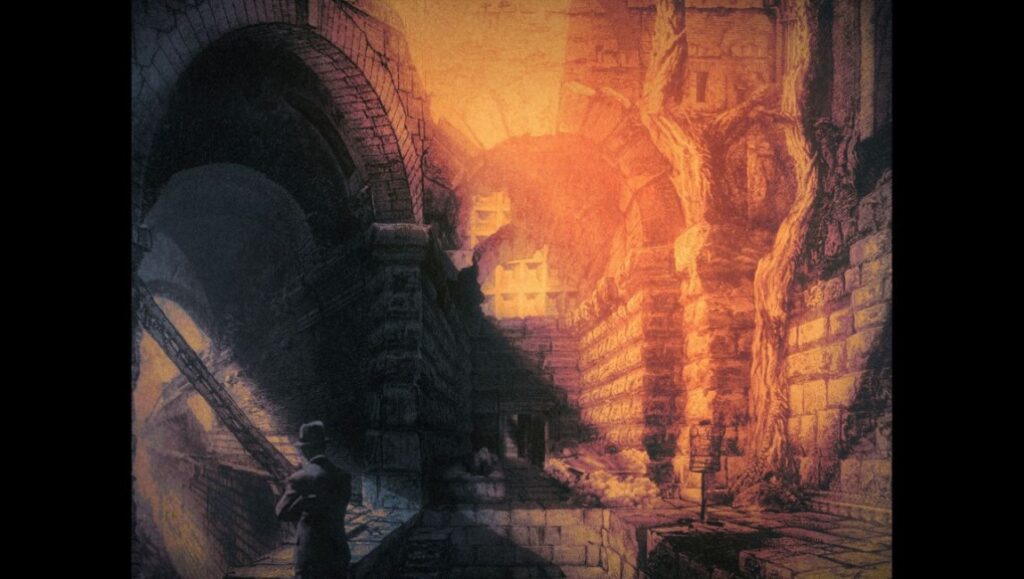

Opening with the ominous chirping of birds and thundering explosions in the sky, Fairytale reveals its comically absurdist tone and atmosphere through the juxtaposition of a biblical quote — “You strangled Satan, passion bearer, with the godly strings of your suffering” — with an encounter between the Communist dictator Joseph Stalin (newly awoken on his deathbed) and Jesus Christ. Much of this absurdism is somewhat reminiscent of Jan Švankmajer, although Sokurov’s dark, fable-like satire (which one may regard as an essayistic mockumentary) incorporates a very peculiar and novel technique of synthesizing deep faked archival footage with a series of animations into a dreamlike, chimerical collage of charcoal. Set in a purgatorial space in which the infernal quartet of Second World War dictators (Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, and Churchill) appears as if resurrected in death, Sokurov reanimates their bygone ghosts to remind us of the vanities and horrors of the 20th century; that while they may be invisible, they still persist and haunt the present. Within this temporal and spatial dead zone, the men of power and tyranny meander, carelessly and with a sense of glorious self-satisfaction, through a phantasmagoric landscape of ruins and corpses. The infamous foursome, engaged endlessly in conversation (or, more accurately, a hallucinatory and lyrical blend of riposte and soliloquy), are playfully reimagined as still entangled in reality, in their futile ideals and egos, manifesting their high hopes for a future now past. They talk excessively, sneakily mock and insult one another, admire their inglorious achievements, and — most comically — overlap, multiplying corporeally and mirroring one another through various versions of themselves.

The overlapping monologues and dialogues, the free-floating streams of monochromatic and expressionist images, the repetitive actions and gestures, the ambiance of poetic surrealism, the eerily gloomy beauty; all these contribute to Fairytale’s misty, post-apocalyptic wasteland in a way that deliberately stops time and stifles life. Sokurov’s aesthetic and thematic strategies, underscored in the central motif of repetition, help cement in the film’s circular and agonizingly slow-paced montage an undivine comedy of eternal, irredeemable damnation. The film’s deliberately atemporal and non-spatial milieu reunites its eternal inhabitants in a seemingly (and admittedly painfully) aimless conflagration of eccentricity, but — even as a minor riff, compared to the enormity of the filmmaker’s oeuvre — it still provides, through its epic and visual virtuosity (one of the most notable scenes is when we see a flood of masses/victims march in distorted images to orchestral music), plenty to muse over. As a multilayered and crucially complementary work to Sokurov’s previous output, Fairytale reconsiders the ever-present horizons of humanity’s past, and somberly suggests that these once-vistas may still be malevolently reincarnated for the future.

Writer: Ayeen Forootan

Love Dog

Slow cinema miserabilism — right up there with elevated horror and anything written by Steven Knight (Serenity gloriously excepted) — is among the most irksome modes of filmmaking from the past half a decade, and has become a frustratingly pervasive festival circuit mainstay. By and large, films that fall under this umbrella tend to be fungible products — anonymous documents constructed of signposts for built-in audiences to spot and rain down empty praise upon accordingly. Of course, slow cinema has birthed some of the millennium’s most essential cinematic voices, but the vast influence cast by such luminaries — and the very serious and programmatic nature of international film festival slates — means waves of ill-equipped directors and their vapid aping have increasingly made a sport of cribbing superficial texture while porting over nothing of their touchstones’ substance.

It’s always a welcome surprise, then, to come across something like Bianca Lucas’ Love Dog. The logline is simple: John (John Dicks, in his debut) has returned to his hometown after the death of his girlfriend. It seems he has no real plans other than to be here and not be there, and articulates no clear designs throughout the film either. Rather, his existence over these weeks (or perhaps months; time is slippery here) is one predicated on distraction and avoidance. He’s a man obviously suffocating in grief, but he refuses to let it touch him: there’s a centerpiece scene of absolutely crushing emotional negation, wherein even the briefest intimacy — a hand resting on the titular dog’s paw while lying on the floor together — cracks a fault line through his placid façade. Instead, he mostly gets drunk and cycles through a sea of strangers on Chatroulette, an attempt to cast himself out of his own battered psyche and into the twisted sideshow of Internet “connection.”

That synopsis isn’t an uncommon one, especially in the world of low-budget indie cinema, but Lucas, who was trained at the Bela Tarr-directed Sarajevo Film Academy’s Film Factory, is too savvy to trade in cheap emotionalism or a bland redemption tale. The director pushes slow cinema’s observational quality even further toward the documentary form, locating John within an empty home and allowing his presence, his fractured interiority, to spill out, filling this space with his own hauntings. Lucas shoots much of the film in tight close-up, often in profile, littering in plenty of over-the-shoulder shots while John is in motion, while elsewhere framing him within doorways or centering him in open, empty rooms. John moves between dangerous energy and controlled resignation, at any moment seemingly see-sawing between recovery and surrender, the viewer fixed as an immediate voyeur to his polarities of mood. It can often feel as if the entire frame becomes the man, the world, too: radio snippets alluding to Covid (though not by name) barely register, and certainly hold no threat. But it’s when John isn’t alone that Love Dog lands some of its most moving moments. Acting as a counterpoint to his anonymous Internet engagement, John is sometimes almost cast as documentarian, delivered in a few standout sequences where he ingratiates himself into the hopes and pasts of strangers (and friends) he encounters — most notably, a young woman who wants to appear on The Voice — a respite from suffering’s isolating forces.

It’s in these details that Lucas’ impressive feature moves beyond the bounds of generically dire arthouse fare. John isn’t a canvas upon which the director paints any empty pretensions, but a character vibrating with wounded humanity. Lucas understands how grief can be an anchor, and examines what it can look like when one moored in this way begins to fold in on themself. Information is patiently doled out, often as a direct reflection of John’s moments of slippage: even the flashbacks, which are brief and oblique, lack any diegetic sound, a partial intrusion on a mind alternately craving and willing itself against their presence. Love Dog doesn’t quite stick the landing — there’s a heavy-handed and unnecessary metaphor in the film’s final moments that muddies the restrained tenor Lucas executes for most of the runtime — and she is admittedly refashioning some shopworn parts to construct the film’s narrative. But those are minor quibbles for a film this delicate, one that so understands the menacing clamor of silence and calm in a broken soul. There is no huff here, there is no bluster, there is no combustion. Love Dog simply, and with great compassion, documents the first tentative steps of an ascent from the hell of one’s own despair.

Writer: Luke Gorham

Matter Out of Place

Early on in Nikolaus Geyrhalter‘s new film Matter Out of Place, a man investigating an unearthed landfill site utters the phrase “out of sight, out of mind.” He’s referring specifically to our society’s propensity for burying its unwanted detritus, but it’s also a useful summation for Geyrhalter’s entire modus operandi. The Austrian filmmaker has built his career on showing viewers those things which typically remain hidden, the corners of the world where assorted “others” do the dirty work of fueling developed nation’s appetites — literally in the case of 2005’s Our Daily Bread, or more broadly metaphorical, as in 2019’s Earth. Here, Geyrhalter has turned his camera to the tons of junk accumulating all over the world, the remains of our collective unfettered consumption, tracing a winding journey from collection to transportation to disposal. Filmed on and off over the course of four years (in part due to Covid disruptions) on several continents, Geyrhalter’s now familiar fixed-camera, tableaux-style compositions attempt to take in the full enormity of our waste. It is eye-opening, to say the least.

An opening title card informs us that “matter out of place,” or “moop,” refers to “any object or impact not native to the immediate environment.” Shots of a beautiful, snow-capped mountain range reveal upon closer inspection acres of plastic garbage scattered around the edges of a river bed. Next, we cut to an excavator digging up a spot in a large, flat field. After several scoops of turf and dirt, the machine begins pulling up scrap metal and old tires, amongst other bulky waste. Two men converse, some of the only audible dialogue in the film, discussing the various waste sites scattered around where garbage was buried and then covered up. This process of consume-discard-hide is essentially Geyrhalter’s thesis, and the remainder of the film largely eschews broader contextualizing, instead allowing long sequences to play out in images sans commentary. As is typical for Geyrhalter, there are no title cards identifying specific locations, although one can occasionally glean an identifying landmark or catch some of whatever language is being spoken. From Switzerland and Austria to Albania and Nepal, Geyrhalter watches garbage get collected, then disposed of in various ways.

One section finds a man going door to door receiving trash from a neighborhood and stacking it up on a push cart. The cart is eventually emptied into a truck, which then joins a huge convoy that makes its way through muddy, winding roads to a huge landfill, where the trucks take turns dropping their cargo. Another sequence follows a similar trajectory, except now at a posh ski resort in the Swiss mountains. Several scenes feature mind-boggling feats of large-scale engineering, like huge incinerators found in Austria, or a massive concrete structure that allows garbage trucks to dump waste directly into its gaping maws that funnel trash directly into a landfill. The main trajectory of the film, its organizing principle, is this movement of garbage away from those who are creating it to far-flung locations removed from daily life. Indeed the film ends with men sweeping the desert, part of The Burning Man Festival’s “leave no trace” policy of cleaning up after the event is over. They’ve successfully cleaned the concert grounds, but the entire film has been spent showing viewers exactly where the garbage these people have collected is going. Ultimately, we are just shifting piles of disgusting shit from one place to another. Geyrhalter knows very well that “out of sight, out of mind” is destroying the world, and he wants to make us look at it.

There’s a kind of hypnotic, monotone quality to Geyrhalter’s work. He tends to hold shots for long intervals, allowing an action to transpire in real-time from beginning to end (in this case, many scenes of garbage trucks unloading in various locales). It’s never boring, not exactly; instead, it speaks to the enormity that he is trying to capture, these frequently beautiful landscapes that have somehow been ruptured or otherwise upended by humans. Geyrhalter isn’t an essayist, nor is he lecturing, but there is a political point of view in his films. We might find a kind of fascination or even an odd beauty in all this decay, but it all adds up to something so unfathomable that no camera can adequately record it. Ultimately, Matter Out of Place becomes an essential part of a loose trilogy alongside Our Daily Bread and Earth. Each captures one aspect of humankind’s constant pillaging of natural resources, irrevocably altering the land as we skip toward our collective demise.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Before I Change My Mind

The needle-eye gateway of the coming-of-age film is a near-obligatory rite of passage for the “emerging” Canadian director. Accordingly, Trevor Anderson sets his debut feature, after over a decade of shorts, in his own nostalgic rearview of 1987, and the restlessly titled Before I Change My Mind begins with a hacky pariah opening somewhere adjacent to the John Hughes of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. It’s to the film’s credit, then, that this is a feint. The nostalgia is tempered by specifics: protagonist Robin (Vaughan Murrae) lives in a barely furnished post-divorce (or worse) home where they appear to have two choices of activity: lying on a bedroom floor or sitting in a living room; the euphoric high-point of the school year is a band trip to West Edmonton Mall that ends with Robin and a friend lost, sitting on the ground next to a vending machine; and neither Robin nor their closeted crush Carter resolve neatly into victims or perpetrators of cruelty.

This isn’t to say Before I Change My Mind is accomplished, exactly. Anderson has previously said he wants to avoid the two poles of “trauma porn” and “inspiration porn” in his work, and the film seems to be overly conscious of these points, avoiding exploitive extremes while still remaining in an easily parsable narrative mode. Most overtly, like many a mainstream American comedy of the 2010s, space is made for a staged revisionist response to what high school ought to have been like if the social order was rearranged: Anderson himself appears as a drama director, cool, wise, and with a slightly self-consciously inflated ego. His play within the world of the film, a camp musical dubbed Mary Magdalene: Video Star, provides an extracurricular magnet for the outcast ensemble of the film to gather around and feel safe within, no mean feat in late-’80s Edmonton, Alberta. It also allows a stage for the musical desires of the director to briefly play out, even as the rest of the film is safely within the bounds of the adolescent genre.

Perhaps the most notable feature of Anderson’s film, then, is how it positions Robin. Despite their appearance as a sympathetic protagonist, we are not given a strong external perspective (like their father or a teacher), nor, aside from some brief, apparently searing-to-the-touch VHS-filtered flash-memories of their mother, an internal one. It would be too much to even say that Robin is estranged from their subjectivity: instead, Anderson might be viewed in contrast to a filmmaker like Stephen Cone, who has similarly worked with unproven actors and complex, ensemble-driven narratives. Where Cone thrives on diffuse immersion into the evangelical milieus of heavily guarded suburban families, and stumbles whenever he inserts stakes-raising plot developments, Anderson seems to have little interest in demanding much from his actors, and keeps things unbalanced by allowing plot elements to build in conventional ways, as long as they don’t resolve in the same fashion. Robin is only as meaningful as their plot — their hidden experience and backstory are not this film’s concerns.

This can also be seen with Robin’s father, played by Winnipeg filmmaker Matthew Rankin (The Twentieth Century), whose narrative only incidentally overlaps with Robin’s. In a TV plot, his dating misadventures would echo or contrast Robin’s, and dovetail or at least meet up in the end — none of this is the case. Anderson seems to want to afford each of his characters a kind of egalitarian autonomy, though not strictly. The strongest of the child actors in the film, Lacey Oake (who plays the star of the stage pageant, Izzy) brings the film closest to the lesson-based middle-ground the coming-of-age drama often gravitates toward. She is poised and, when Carter violently lashes out, or Robin is overwhelmed and shuts down, knows the right things to say and do. In this way, Anderson ultimately shapes Before I Change My Mind’s narrative to be messy without being overly provocative; it exists in an intentionally compromised state, where all of its pieces show signs of volatility, but the desired output is, like Robin’s art sketches, a kind of loving caricature to be invested with enormous meaning, regardless of the finer details of the form it takes.

Writer: Michael Scoular

It Is Night in America

Ana Vaz’s meditative documentary on the conundrum of wildlife habitation, as considered through the intensified processes of urbanization, is a more frustrating exercise in atmosphere than an attuned critique. It is Night in America appears, at first, to be a beautiful, elegiac estrangement: a cityscape observed from a rooftop, panning crudely in an extreme wide shot to the right as perhaps a nod to Akerman’s final shot in her making-of documentary, The Eighties. Initially disquieting and patient, the anonymity of apartments and skyscrapers pulsating on 16mm — texture oozing from the celluloid and coloring the shadows — the film instead hurriedly abandons its formal vocation to insist upon rigid perspective. The opening extreme wide shot cuts to a close-up, the panning intensifying in speed; the buildings are abstracted into blurs. Now, those images of alienation are screaming for attention, and any nuance quickly dissipates, never to return. During the film’s remaining runtime, Vaz posits a juxtaposition: the city in its autonomous isolation vs. animals in captivity. Voiceover is even incorporated to underline this already obvious dichotomy, inundating the work with interpassive postulation.

Vaz ogles the animals, a telephoto lens aimed intrusively upon their confusion and solitude, seeking to extrapolate nothing more than atmospherics, aided by the pairing of her use of celluloid and an operatic brass score. The question, then, is why does the film seek to extract poeticism from these circumstances? The animals cannot consent to their representation, and yet their displacement is still made spectacle of — given its ostensible thesis, is this not a matter of ethics that the work should be contending with? We have such power in the wielding of the image and we ask so persistently what that might be indicative of as we abscond with the impressions of human beings, but are those questions of ethics and morality not to also be considered when leering at the removed agencies of animals? While the footage of the city is fragile and decorative, while the orchestration of the score itself is effectively portentous, the gross aestheticism and self-insistence on what the film is about tarnishes what has the capacity to be a reflexive dual critique of compliant gazes and urban sprawl.

Writer: Zachary Goldkind

The Adventures of Gigi the Law

There’s a relaxed tone to Alessandro Comodin’s The Adventures of Gigi the Law — one that’s so lackadaisical the film often threatens to stall whenever there’s a moment of inactivity, which constitutes about 90% of the motion picture’s runtime. Take your pick for the film’s most thrilling set piece: perhaps it’s when our belligerent central protagonist, police officer Pier Luigi Mecchia, gets in a verbal altercation with his next door neighbor about trimming his overgrown trees, and then later enters into another passive-aggressive argument with him that same day — or maybe that actually occurs later that week, as the film never establishes a clear, linear temporality in relation with its character’s actions — wherein Gigi, at first, offers to cut them down, right before immediately doubling back on his word and, sometime later, publicly smears his good name. Or maybe the most tantalizing moments comes when Luigi is first introduced to a young new dispatcher named Paola who provides him with step-by-step directions to a domestic dispute that ends up being a false alarm? Even when something “exciting” finally happens — a little girl throws herself under an oncoming train — there’s a stark monotony to the way people react and process the world around them, or at least in regards to this specific cultural and sociopolitical region (northern Italy). The unnamed girl’s death is never resolved, nor are the countless other faceless suicides that follow in the aftermath; Luigi, through it all, keeps on driving around town, spewing the same old lame double-entendres, acting like everything is okay when it very clearly isn’t.

While there’s a strong thematic throughline within this rather carefully structured docudrama, one that reflects a clear personal understanding of these modest people and their wistful way of life — Luigi is Comodin’s real-life uncle, who serves in the same village Comodin was raised in — it’s hard to ever truly embrace or pin down just what exactly the film is going for on a tonal level. There’s a slightly romantic tinge to Luigi’s outlook on life, but one that’s constantly challenged and even mocked; he’s openly told how little his fellow colleagues like him, yet he’s still granted a heroic ending and girlfriend half his age (it may/may not all be a dream, but those thinly-conceived stakes have little functionality outside of pure narrative contrivance). A general sense of ambivalence takes hold, which fits the film’s temperament far better than any of the other genre-adjacent non-starters that are attempted before; Luigi keeps going because that’s all he really can do to make sense of it all. So drive around he does; in fact, it’s all he ever seems to do! He swaggers about in his beat-up police cruiser, always shot at medium-length in long, unbroken takes that simultaneously document the desolate Italian countryside his fellow citizens inhabit; in a sense, you can call this a stealth landscape film, one with a lot more movement than most. But even a label as fluid as that one doesn’t really do The Adventures of Gigi the Law much justice, as it comfortably exists outside of the strict borders of such easy classification. For those willing to take the ride, there are few adventures from this year that will seem this equally (and paradoxically) tedious and tantalizing.

Writer: Paul Attard

Comments are closed.