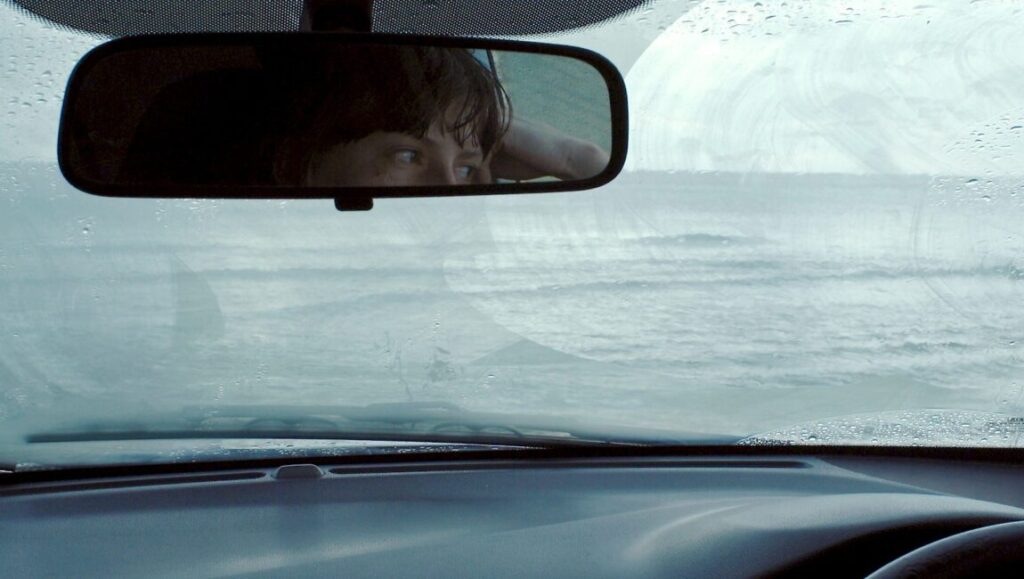

The narrative framework of Helena Wittmann’s Drift revolves around two women, each going their own separate ways after spending some time together in northern Germany. One of the women intends to return home to Argentina; the other, who Wittmann’s film spends most of its time with, sails out to sea. In the early sections of Drift, even when the women are together, neither rarely inhabit the frame at all — and even more rarely do they share it. Drift more often consists of wide, static shots of landscapes; and these, taken as a whole, seem to comprise an abstract narrative in and of themselves. The human part of the film, then, becomes more of a lens through which these landscape shots can be read: repeated images of waves crashing out in the middle of the Atlantic take on an affective meaning that they otherwise wouldn’t have. In fact, for about thirty minutes in the middle of Drift, the ocean is all that’s seen; an image of the sailing woman dissolves into a shot of the ocean, and the woman then remains offscreen until her ship makes landfall. This is the film’s best section, free as it is from the burden of narrative momentum. The slow montage of the ocean in its many states — in the day, at night, empty, full of fish — becomes hypnotic, and natural sounds of the sea give way to a pulsating score.

It’s not the structuralist experiment that matters here, but rather the application of that language to an affect.

When the sailing woman returns to land, she video-chats with the friend from Germany, in effect ‘digitally’ manipulating the distance that’s been put between them through the geography of the film. In this sequence, Wittmann creates an obvious homage to Michael Snow’s Wavelength, slowly zooming across the room towards a photograph of the ocean on the window. Wittmann’s zoom is much faster than Snow’s, and fits more neatly into a preexisting framework, rather than creating its own through the camera movement. It’s not the structuralist experiment that matters here, though, but rather the application of that language to an affect. When the camera reaches the photograph, it is closing the temporal and geographical space in much the same way that the Skype chat is closing the distance between the women. This is a softer structuralism than its reference point, relying less on intellectual rigor than emotional inference in order to achieve its ends. To watch Drift is to contemplate the spaces people cross in their minutiae — and at the film’s best, Wittmann finds common beauty and luxuriates in it, creating a meditative and engaging experience unlike much else.

You can currently stream Helena Wittmann’s Drift on Mubi.

Comments are closed.