Cary Joji Fukunaga’s Sin Nombre bests its Disneyfied cousin Slumdog Millionaire in nearly every way. Whereas Danny Boyle’s film is frenetically shot, frantically paced, and emotionally ineffective, Nombre is often patient, taking its time to develop its character and give its audience a chance to have more of an investment in them. Both are essentially adventure stories; one set in the bustling metropolitan city of Mumbai (Slumdog), and the other a high-stakes, on-the-run thriller navigating the treacherous landscape of rural Mexico (Nombre). Both directors are enslaved to the predictable narrative formulas of their native countries, and both rely on aesthetic crutches (the relentless musical score never lets up in either film). But where Boyle gives in to the tantalizing prospect of being a crowd-pleaser, Fukunaga’s feature is willing to take risks, and the director shocks his audience in ways that usually feel organic and unforced.

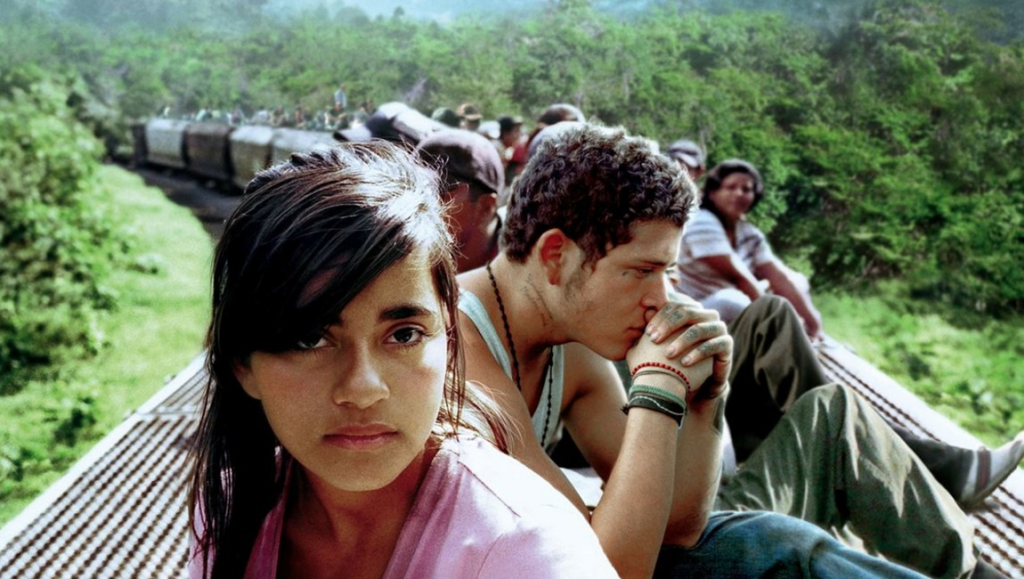

The narrative is split between two central characters: Mexican gang member El Caspar, played by compelling newcomer Édgar Flores, and Sayra (Paulina Gaitán), a young Honduran girl emigrating through Mexico with her father and uncle. There’s also “El Smiley” (Kristian Ferrer), a new inductee into Caspar’s gang who’s later charged with killing his friend. As Caspar’s life is falling apart, Sayra and her family pass through his hometown on their rough journey north. Following a series of unfortunate events, both end up riding on the roof of the same train, and later find themselves on the run from Caspar’s bloodthirsty gang leader, El Sol (Luis Fernando Peña). Sayra and Caspar make a mad dash for the freedom of the border, and Fukunaga ably keeps the tension mounting until the film’s final, devastating moments.

Cinematographer Adriano Goldman (“City of Men”) deserves the lion’s share of credit: his lensing is evocative and artful without calling too much attention to itself; the half-naked, tattooed bodies of the El Mara gang are given a sun-baked hue, and gliding shots during the various chase sequences recall the urgent set pieces of Slumdog Millionaire, without ever feeling as gimmicky or gaudy as that film. As the director and writer of Sin Nombre, Fukunaga deserves about as much praise as he does criticism. He doesn’t explore the culture of the El Mara very deeply; unlike David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises, for instance, no meaning is given for the gang members’ tattoos, nor much of anything else that characterizes them. And, although we come to care for Caspar and Sayra as individuals, their emotional connection to each other isn’t as developed as it could have been, thanks to a slightly rushed third act. After completing a similar film, 2003’s Rio De Janeiro gangster flick City of God, Brazilian filmmaker Fernando Meirelles went on to make some of the most grossly overrated Hollywood fare of the decade (The Constant Gardener, anyone?). Although Sin Nombre hasn’t yet received the critical plaudits that Meirelles’ film did, he’s in a similar situation as a filmmaker. Fukunaga’s debut displays enough artistic merit and understanding of the culture he’s portraying to outweigh its plot contrivances and ill-advised aesthetic choices. But it’s where Fukunaga goes from here that will determine his strength as a filmmaker.

Comments are closed.