Just as Woody Allen keeps demonstrating a preference for leaving behind a depressing legacy of quantity over quality, that other favorite Great American Director, Clint Eastwood, also seems intent on putting out as many movies as he possibly can before he heads for the hereafter. The strategy paid off in spades around the first half of the last decade when, after producing over five years of misfires like Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and Blood Work, the filmmaker reasserted his formalist and dramatic chops, first with the operatic police saga Mystic River in 2003, and then with his Best Picture winner, Million Dollar Baby. For a minute there, it looked like Eastwood had returned to the glory days of his mid-’90s artistic high, recreating his muscular/melancholy diptych of A Perfect World and The Bridges of Madison County.

Eastwood would manage to triumph with more career-defining (if not greatest) work, the Iwo Jima twosome Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, then spend the next few years, like Allen, pumping out a string of duds, including last year’s ham-fisted Obama allegory Invictus and the hysterical cluster-fuck that is Changeling. The most frustrating thing about these last two films is that, unlike the Iwo Jima block, you can’t really blame their flaws on Clint’s screenwriters; Invictus climaxes in one long sports cliché that grossly undercuts its attempted emphasis on communal catharsis, and Changeling is a wretched cocktail of tonal fissures, narrative digressions, moral inconsistencies, and didactic tedium. One should be excused for having lowered expectations coming into Eastwood’s latest, especially considering reports that Hereafter was a Peter Morgan-scripted supernatural romance mosaic, with plot descriptions that sounded like some ungodly fusion of Phenomena and Crash.

But here’s the thing about both Eastwood and Allen: For all the maddeningly dumb techniques in their respective arsenals, there are certain motifs and recurring themes that endear them to us, and there’s an appeal to that which not even volumes of auteur theory could entirely unpack. Hereafter drops the dense plotting of Changeling and the sandwich-board politics of Invictus to expose the resonant, character-to-character dynamics that have been the hallmark of his best films over the last decade-plus. The director hasn’t been this tender and non-confrontational since The Bridges of Madison County, and while some will find this script’s relative uneventfulness (the main action takes place in the first reel, followed by a lot of moping) to be the movie’s greatest failing, there are few filmmakers who do somber reflection and melancholy like Clint. Hereafter is sentimental to a fault and, as is almost always the case, Eastwood is working with severely sub-par material, but he invests it with such world-weary humanism that it cuts deeper than it really has any right to.

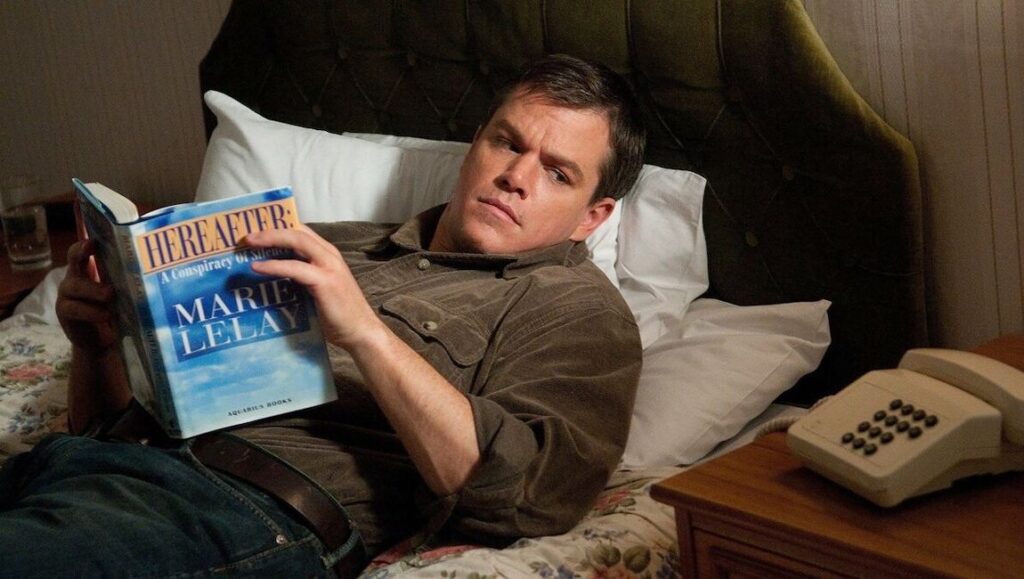

Hereafter is essentially a treatise on accepting death, one that deals in three parallel stories of grieving and catharsis. Matt Damon’s section gets the lion’s share of attention, but his thread, about a San Francisco psychic who forsakes his lucrative gift upon realizing it’s ruining his life, shares equal time with the other two. The least successful of these is built around French TV journalist Marie (Cécile de France), who survives a near-death experience during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami while on vacation with her producer boyfriend (Thierry Neuvic), and becomes obsessed with leveraging her celebrity into a book deal while hoping to meet others who may have seen the same divine images that she did. This thread is more remote and privileged than the other two, and de France is so wooden that the emotional momentum Eastwood hopes to generate in her narrative never quite materializes. More successful is the third panel, which finds eight-year-old Marcus mourning the untimely passing of his twin brother, Jason (played by real-life identicals Frankie and George McLaren), and searching for a medium who can open a line of contact between them. Unsurprisingly, these threads eventually converge in a series of transcendental encounters that say as much about the human condition as the communal pity party that closes Crash. But what Eastwood does to get there stays with you.

Offsetting supernatural hokum — recurring graphics that resemble something out of TV’s Medium, if not Casper the Friendly Ghost — Eastwood’s greatest conceptual bid posits that the titular “hereafter” refers to a purgatory state in which the lonely wait until they’re ready to pass on into their next “life.” Think of Hereafter as the last season of Lost, in miniature, while never explicitly spelling out that series’ leaden conclusion. It’s a concept that gradually reveals itself through visual motifs (all three principals are, at some point, shot against a looming sky), and the shades of melancholy the filmmaker evinces. Damon seems perfectly in sync with this, turning in his most somber and reserved performance while mostly sidestepping histrionics. It’s the second time he’s elevated an Eastwood picture; he more or less nailed his role in Invictus. This isn’t really awards-caliber acting, but it’s the kind of performance that lends to the tonal strengths of Eastwood’s aesthetic. Equally memorable is Bryce Dallas Howard as the Damon character’s short-lived love interest. She doesn’t have a particularly lengthy amount of screen time, but she does figure prominently into the film’s most wrecking ball-emotional sequence.

It’s good to see Eastwood returning to this more intimate mode, and it’s refreshing to see a film of a spiritual nature that largely avoids the topic of religion. But not even the most staunch Eastwood defender can deny that Hereafter is compromised. It’s failed by a frequently inept screenplay, especially in its last act, and by plainly generic dialogue (not once but twice does Damon’s character espouse the angst-ridden cliché, “It’s not a gift, it’s a curse!”). Not even with a reliably strong score and evocative use of shadow and contrast can the director make his roundelay narrative as engaging as it needs to be. The good news? Perhaps it’s too early to put Clint’s trajectory of decline into the same class as Woody’s. While the latter has alternated between the same two templates for decades, Eastwood continues to actively pursue diverse material, bringing a distinctive directorial identity to everything he’s involved in. There’s been a few good ones and recently quite a lot of bad ones, and if Hereafter isn’t quite applicable to the former category, it also doesn’t deserve to be grouped with the dregs of Clint’s filmography either. Instead, it lies somewhere in between. Which would seem appropriate.

Comments are closed.