Abbas Kiarostami has never been shy of image manipulation in his documentary films. One almost hesitates to call Close Up a documentary, for instance, because of this manipulation, since no one can truly understand how much has been restaged or “acted” and how much should be taken as truth. Certain dubious scenes in Close Up—namely, Sabzian’s trial—pose more philosophical questions about the entire cinematic exercise than they answer, which is partially why the film is ultimately rewarding. Kiarostami’s post-Revolution preoccupation with the treatment of children in Iran inspired him to make the deeply spiritual Where Is the Friend’s Home? and the less substantial A Suit for Wedding and First Graders, all of which examine the environments in which children face everyday abuse. But none are as devastating as Homework. In this documentary investigation, Kiarostami examines the burden of homework, a problem mostly obscured by its private nature. For most viewers, the idea of doing schoolwork at home is an innocuous if not annoying task. But in Iranian society in the 1980s, Kiarostami argues, homework is much more than a chore: It is a whipping post that provides parents and teachers with a convenient excuse to mistreat children. Homework is the yoke that ties kids’ public existence in school to their private lives at home, and it reveals much more about parent-child and teacher-student relationships than a child’s cognitive abilities in spelling or equations.

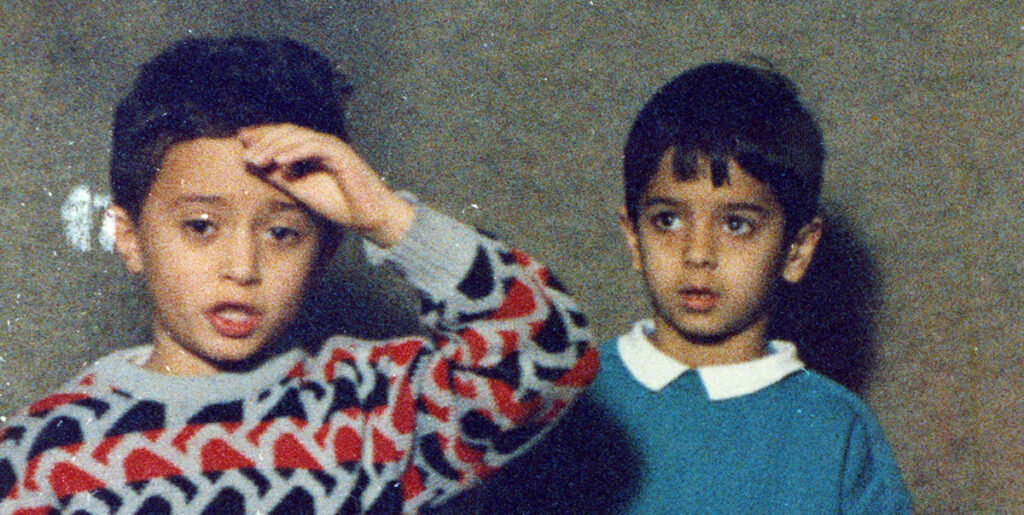

To conduct his research, Kiarostami kept things simple and picked one school of young males. Kiarostami says he surveyed 800 students, parents and teachers, in order to unearth the difficulties children experience in completing their assignments. The project is a personal one; its predecessor can be found in its fiction equivalent, First Graders. Kiarostami was given the tremendous responsibility of taking care of his two sons after separating from his wife, and he experienced difficulty helping them with their assignments. He was curious if this problem was unique, and within minutes of watching the film it becomes fairly obvious that the director is not alone—many parents struggle to assist their kids with their homework, and for very diverse reasons.

What emerges from this hour-long doc, consisting mostly of interviews with kids, is that the role of Iranian children is one of a scapegoat for any and all household problems. Homework is not as manipulated as Close Up; its structure is too simple, its purpose too straightforward. But because it is difficult to accept Kiarostami’s interviews at face value, trying to discern what is being manipulated in this film offers no real value in its analysis or criticism. We know from the beginning that there is enough child abuse occurring among the students to warrant an exposé that focuses only on the most troubled victims (Kiarostami says that he picked the least academically inclined children, but of course there is a high correlation between the at-risk kids and the ones at the bottom of their class). There are repeated shots of the camera operator focusing a lens (without any onscreen sound) that were obviously thrown in after shooting. Kiarostami can be heard mostly off-camera asking questions and his physical presence is shown a few times. None of this is problematic or deceptive or even interesting, really, in the overall scheme of things. What is more important is the clear deterioration of the interviews as the film contrasts the best-mannered students with the most troubled, particularly the last child, whose extreme anxiety is not only disconcerting to watch, it makes one wish there had been some pathway for intervention. The child is terrified of the film crew and demands his friend accompany him in the room—for no reason, he claims. When his friend is interviewed separately, he says the other boy was scared to be in a room with adult strangers because he assumed they were going to close the door and beat him with a ruler. Because there is no observable cause for his panic, one senses that the child’s look of terror and his pleas for mercy are behavioral—more telling of his family situation. (Kiarostami does interview his father, albeit quite delicately, because a subtle and restrained approach discloses much more about the father’s half-hearted lies than straight-up interrogation.)

What emerges from this hour-long doc, consisting mostly of interviews with kids, is that the role of Iranian children is that of a scapegoat for any and all household problems.

There are a few noticeable trends among the children’s answers that divulge the systematic communication strategies they have been taught in order to survive in the classroom and at home. One comedic (though tragic) pattern emerges when every student righteously affirms their preference of homework over cartoons. In at least one case, Kiarostami does not even need to pose the question; the child immediately denounces cartoons over the value of “learning” derived from homework. Said homework is found to be perplexingly difficult, heavy in load, and more often than not composed of busy-work drills. Because teachers demand that students essentially teach themselves at home, homework absolutely requires the supervision of an older family member. Frequently, adults are too busy, illiterate or negligent to live up to this responsibility and are unsure how to help their children succeed. But the real contradiction lies in discipline and reward. Instead of acknowledging the hardships placed on children in completing their homework (they are physically punished at school if their homework is incomplete), many parents are quick to blame their kids for not acing every single test. Kiarostami asks most of the children about punishment, and while many are too shy initially, they almost always open up about who punishes them , the objects used in the beating, and its frequency. Many of them don’t understand what the word “praise” even means.

These children have been taught to lie, but they are too young to understand nuance to effectively pull off deception. The gravity of their situation becomes clear in a short period of time. In his fiction films, Kiarostami is capable of weaving the god-awful truths with the many lies of his proud characters, but in Homework reality does the job for him. This does not make him lazy; the strategy communicates alarming real-life examples and demonstrates his strength in using different techniques to indirectly unearth the devastating results of questionable social behaviors in Iranian children. Many of his films do not feature the most uplifting of themes, and a few are downright depressing, but real-life circumstances mark Homework as next-level devastation in Kiarostami’s oeuvre.

Comments are closed.