Ostensibly beyond Abbas Kiarostami’s typical terrain—particularly because of its complete lack of optimism—The Report feels like a puzzle piece from another game, if only at first. With the exception of its well-known domestic abuse scene, this cold, embittered “report” on Iranian life circa 1977 is less interested in overt depravity than it is in the revelatory comments and gestures of periphery characters, which signify a deeper intersection of attitudes and morals (this also reminds the viewer that they are, indeed, watching a Kiarostami film). The Report almost plays out like an eerie premonition of the riots against the corrupt Shah—which turned into the 1979 Revolution, forever changing the country’s social structure. Given the more light-hearted nature of Kiarostami’s previous work, production context is absolutely necessary to understand how such a grim outlook on life crystallized into his second true feature-length film. The country was in great political upheaval and Kiarostami himself faced several personal dilemmas at the time (including divorce).

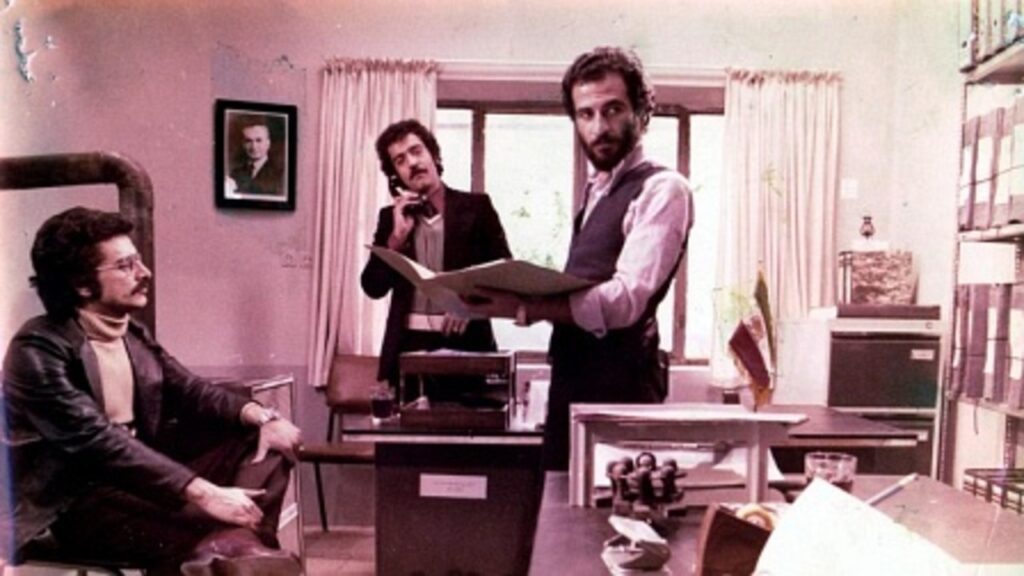

The Report‘s protagonist, Mr. Firukhzai, is the least likable in Kiarostami’s oeuvre, a contemptible tax investigator who procures bribes from the citizens he’s supposed to serve, uses his knowledge of property law to prevent eviction from his home, and physically and emotionally abuses his wife. It’s a little disheartening to hear Kiarostami describe The Report as a “self-portrait,” though of course that would place too much literal importance on the reflection of an author’s life in his art. Like many Kiarostami characters, Firukhzai has an air of moral ambiguity tested repeatedly in the film; unlike others, his solutions to problems are never redeemable. There are no uplifting touches to be found here. Kiarostami seems as coldly removed from the film as Firukhzai is from his wife (and the viewer), and that is perhaps why The Report is one of Kiarostami’s least enjoyable features. It’s not that characters are completely inhumane; rather, their apathy and pride are testaments to the desperation that hung heavy in Tehran’s polluted air. The idea of using creativity to solve difficult problems—a theme in many of Kiarostami’s works—became impossible in the late ’70s: Political tensions were at an all-time high, and so too was censorship. Iran’s downward spiral of demoralization was reflected in many (unsurprisingly censored) new-wave films that showed no restraint in their harsh criticisms of every aspect of Iranian society.

Unlike most Kiarostami films of this period, the protagonists of The Report are adults, the themes are neither philosophical nor playful, and certain scenes are quite painful to watch, including a scene in which Firukhzai physically assaults his wife.

The Report is a ruthless social criticism, and while many filmmakers had deconstructed the most frustrating and hypocritical aspects of Iranian life, Kiarostami’s participation in this type of filmmaking had until the time of the film’s release been largely absent. The director had operated almost entirely outside of the Iranian New Wave movement, for, as an employee of Kanun—the government cultural institution that created educational works for children and adolescents—the nature of his work was severely confined. In a sense, Kiarostami was restricted from demonstrating outright dissent, though part of his genius was born from these restrictions, which taught him how to weave in subtle social critiques. Kiarostami hasn’t entirely abandoned this style of filmmaking, either; while his own works became more philosophical later on, he did pen Jafar Panahi’s sombre Crimson Gold.

Unlike most Kiarostami films of this period, the protagonists of The Report are adults, the themes are neither philosophical nor playful, and certain scenes are quite painful to watch, including a scene in which Firukhzai physically assaults his wife. The viewer is spared the visual depiction of this assault, but the sounds of their screams, his abuse, and the increasingly shrill cries of the child almost make it more disturbing. While the row technically functions as the film’s climax, it arrives so loosely and quickly that it feels less like a structured plot point than a regular occurrence in the household—what’s shocking is not its unexpectedness but its absolute normality. Many critics argue over the scene’s supposed graphic nature and its necessity, especially in a Kiarostami film. Yet the ending does somewhat justify its inclusion. When Firukhzai finds his wife unconscious after overdosing on sleeping pills, he rushes her to a hospital, only to find an indifferent staff confident she will survive (without the need of a doctor’s examination). When the nurse scolds him for physical abuse, she adopts a tone that is neither serious nor glib, merely tired—as if she’s seen this too many times to continue caring. This bleak denouement doesn’t entirely neutralize the abuse; perhaps in a better Kiarostami film, it would only be hinted at rather than be made explicit. However, its inclusion does make the fairly quiet ending seem that much more harrowing and awful, especially Firukhzai’s equally indifferent reaction to the staff.

There are other scenes which demonstrate questionable social attitudes, though none like the ending. One still vital scene early on employs a standard Kiarostami device—using the nature of character interactions to symbolize something much larger. Firukhzai becomes agitated by his elderly office servant, whose glass he accidentally broke. The servant demands twice the amount for a normal glass, claiming it was supposedly “unbreakable.” Their petty dispute is not only absurd, it also represents the older generation’s blind acceptance of religious and political beliefs, which the cosmopolitan, young-adult population refuses to take at face value. At first, the battered servant seems like the more reasonable one, for he is simply asking for more money because the glass was more expensive, yet his silence over the fact that the glass was indeed breakable depicts a broader unwillingness to accept the fallibility of one’s beliefs. The Report may be one of the least polished of Kiarostami’s works, but still worth highly recommending, if one ever gets the chance to see it (distribution has been scarce). The film is a fascinating historical record of a culture in tumultuous transition. Kiarostami’s venture into new wave cinema shows us what his work may have looked like had the Islamic Republic not forced his return to Kanun, which offered one of the few remaining creative opportunities inside the country after the revolution.

Comments are closed.