SoundCloud junkies Paul Attard and Joe Biglin run down some rap releases from the months of December and January in the latest What Would Meek Do?. This sixth official issue (after a special edition of the column last month) features takes on a number of embattled artists: Kodak Black, who has had allegations of sexual assault brought against him in recent months; 21 Savage, who had a fraught run-in with ICE in February and since then has been arrested on felony theft charges; and YWN Melly, who’s facing two counts of first-degree murder, and a potential sentence of life in prison. Two out of three of these rappers turn in possibly their best works in the shadow of these controversies; the third one, well… On the other hand, both Biglin Fave™ SBN3 and Attard’s fellow Detroiter Saba Baby have clean rap sheets (that we know of) — even though the latter raps disturbingly about Bill Cosby and R. Kelly. Lastly, our Kicking the Canon pick for this month goes back to the source of this thing we call a “rap project” — with Run-D.M.C.’s 1984, self-titled landmark debut album.

What’s changed for 21 Savage since the release of his debut commercial project, Issa Album? Well, as he puts it on the opening track of I Am > I Was, “a lot.” For one thing, Savage has become a much more technically impressive rapper, stringing together his frightening taunts with a newfound cunning and improved wordplay, lending a prototypical song like “Gun Smoke” an especially menacing delinquency: “Started with a deuce deuce, turned it to a .38 / Then I got a Glock 9, turned it to an AK.” The track “Good Day” samples Three 6 Mafia and interpolates Ice Cube, laying the sonic foundation for a terrifying, modern vision of the trapper lifestyle (“Murder with the .45, murder with the nine / murdering that bitch, put that dick up in her spine”) and throughout I Am > I Was, Savage relies less on his deadpan delivery than he has on past projects, opening up his vocal range and proving as much adept at melodic headache ballads (“Ball W/O U”) as he is whispered bangers (“ASMR”). Maybe the biggest revelation here, though, is that the Slaughter King is growing up: he pens a song to his momma, the only person he displays much admiration for, and has features from ‘serious’ and ‘conscious’ rappers like J. Cole and Childish Gambino — both of whom actually fit here, especially (and shockingly) Cole, who, on “A Lot,” has a verse about liars and cheats in the rap game that’s uncharacteristically sharp. But Savage also gets his younger cousin, Yung Nudy, on closing track “4L”, where the two indulge in one more round of depravity. The message here is clear — it’s right there in the title. 21 proves that he’s better than he once was, while at the same time still proudly proclaiming that he’s “a young trap ass, strapped-ass, no time for the yap ass / Get a n***a clapped ass, Zone 6, ride around with it in my lap ass / Leave your man’s brain in your motherfuckin’ lap ass n***a.” Paul Attard

What’s changed for 21 Savage since the release of his debut commercial project, Issa Album? Well, as he puts it on the opening track of I Am > I Was, “a lot.” For one thing, Savage has become a much more technically impressive rapper, stringing together his frightening taunts with a newfound cunning and improved wordplay, lending a prototypical song like “Gun Smoke” an especially menacing delinquency: “Started with a deuce deuce, turned it to a .38 / Then I got a Glock 9, turned it to an AK.” The track “Good Day” samples Three 6 Mafia and interpolates Ice Cube, laying the sonic foundation for a terrifying, modern vision of the trapper lifestyle (“Murder with the .45, murder with the nine / murdering that bitch, put that dick up in her spine”) and throughout I Am > I Was, Savage relies less on his deadpan delivery than he has on past projects, opening up his vocal range and proving as much adept at melodic headache ballads (“Ball W/O U”) as he is whispered bangers (“ASMR”). Maybe the biggest revelation here, though, is that the Slaughter King is growing up: he pens a song to his momma, the only person he displays much admiration for, and has features from ‘serious’ and ‘conscious’ rappers like J. Cole and Childish Gambino — both of whom actually fit here, especially (and shockingly) Cole, who, on “A Lot,” has a verse about liars and cheats in the rap game that’s uncharacteristically sharp. But Savage also gets his younger cousin, Yung Nudy, on closing track “4L”, where the two indulge in one more round of depravity. The message here is clear — it’s right there in the title. 21 proves that he’s better than he once was, while at the same time still proudly proclaiming that he’s “a young trap ass, strapped-ass, no time for the yap ass / Get a n***a clapped ass, Zone 6, ride around with it in my lap ass / Leave your man’s brain in your motherfuckin’ lap ass n***a.” Paul Attard

Kodak Black’s “Moshpit” ends with the couplet “Fuck a protest / Let’s start a mosh pit in here.” At face value, this seems a bit silly; but what by all indication should be a paint-by-numbers, dumb-fun Juice WRLD collab actually uses its playful, xylophone-led melody, and heightened feelings of juvenilia, to hide an undercurrent of existential political dread. The same can be said of many songs on Kodak’s Dying to Live: the album tracks the social media-broadcasted struggle of Kodak’s own life, post-incarceration, against the systemically-perpetuated feelings of powerless despair that loom over so much of black America (it should be noted, though, that Kodak currently awaits trial in April for a charge of sexual assault stemming from 2016, necessarily complicating the vision of injustice that’s presented here). “Free all my ni**as who stuck in the box / Locked up and watching the clock,” from the track “Calling my Spirit,” might sound like a standard sentiment for any rags-to-riches rapper to espouse, but it’s all too easy to forget that Kodak has been a rapper derided by the media as someone ‘dumbing-down rap music.’ Kodak’s foray into politics never goes full-on Kendrick, either, in that he doesn’t shy away from the marble-mouthed mumble rap he’s known for — in fact, he doubles down. The glitch-pop of “Transgression” finds Kodak letting his words messily tumble over the descending beat: “I did everything the streets told me was cool to do / Now I’d rather prove it to myself before I prove it to you.” But there’s a newfound sense of urgency here — the impression that an embattled Kodak is summoning these words as a means of defense against the criminal justice system. Dying to Live’s opening track, “Testimony,” lays out similar intentions right in its title, but the song has two purposes: it’s both Kodak’s response to his legal troubles and a religious invocation of past sins — a confessional, a way toward healing. In fact, Kodak’s work here overall — his versatile melodies, his poignant storytelling, and his virtuoso use of voice-as-instrument — conflates political and spiritual struggle. And while a stretch of Dying to Live does tone down the politics side (absurdist sex banger “Gnarly” and the cheesy, steel drum-led “Zeze,” both certified radio hits), this section reinforces the strains of humor and joy that run through the album. Most endearing of all, though, is the sense of gratitude that Kodak displays here. On “Malcolm X.X.X.,” a tribute to the late, fellow Floridian XXXTentacion, samples of the civil rights icon explaining how the Islamic faith has been misunderstood by white America are juxtaposed against Kodak’s heartbreaking lament, a concept energized by the rapper running through his own personal aspirations. Throughout all this, though, Kodak never forgets where he comes from — and in particular, the concern for the material (chains, diamonds, designer) that seemingly got X killed. The song delivers a shock to the system, and serves as a strong denunciation of those who “ain’t [already] know” that Kodak “was intellectual.” Joe Biglin

Kodak Black’s “Moshpit” ends with the couplet “Fuck a protest / Let’s start a mosh pit in here.” At face value, this seems a bit silly; but what by all indication should be a paint-by-numbers, dumb-fun Juice WRLD collab actually uses its playful, xylophone-led melody, and heightened feelings of juvenilia, to hide an undercurrent of existential political dread. The same can be said of many songs on Kodak’s Dying to Live: the album tracks the social media-broadcasted struggle of Kodak’s own life, post-incarceration, against the systemically-perpetuated feelings of powerless despair that loom over so much of black America (it should be noted, though, that Kodak currently awaits trial in April for a charge of sexual assault stemming from 2016, necessarily complicating the vision of injustice that’s presented here). “Free all my ni**as who stuck in the box / Locked up and watching the clock,” from the track “Calling my Spirit,” might sound like a standard sentiment for any rags-to-riches rapper to espouse, but it’s all too easy to forget that Kodak has been a rapper derided by the media as someone ‘dumbing-down rap music.’ Kodak’s foray into politics never goes full-on Kendrick, either, in that he doesn’t shy away from the marble-mouthed mumble rap he’s known for — in fact, he doubles down. The glitch-pop of “Transgression” finds Kodak letting his words messily tumble over the descending beat: “I did everything the streets told me was cool to do / Now I’d rather prove it to myself before I prove it to you.” But there’s a newfound sense of urgency here — the impression that an embattled Kodak is summoning these words as a means of defense against the criminal justice system. Dying to Live’s opening track, “Testimony,” lays out similar intentions right in its title, but the song has two purposes: it’s both Kodak’s response to his legal troubles and a religious invocation of past sins — a confessional, a way toward healing. In fact, Kodak’s work here overall — his versatile melodies, his poignant storytelling, and his virtuoso use of voice-as-instrument — conflates political and spiritual struggle. And while a stretch of Dying to Live does tone down the politics side (absurdist sex banger “Gnarly” and the cheesy, steel drum-led “Zeze,” both certified radio hits), this section reinforces the strains of humor and joy that run through the album. Most endearing of all, though, is the sense of gratitude that Kodak displays here. On “Malcolm X.X.X.,” a tribute to the late, fellow Floridian XXXTentacion, samples of the civil rights icon explaining how the Islamic faith has been misunderstood by white America are juxtaposed against Kodak’s heartbreaking lament, a concept energized by the rapper running through his own personal aspirations. Throughout all this, though, Kodak never forgets where he comes from — and in particular, the concern for the material (chains, diamonds, designer) that seemingly got X killed. The song delivers a shock to the system, and serves as a strong denunciation of those who “ain’t [already] know” that Kodak “was intellectual.” Joe Biglin

Florida crooner YWN Melly is largely concerned with two things: romantic woes and murder. For every “Murder on my Mind” that the 19-year-old pens, he has a couple of banal love ballads in his back pocket. His delivery isn’t anything particularly original; Fetty Wap was doing this sorta mumble rap/canorous moan thing long before Melly turned his homicidal thoughts into a breakthrough. So just what does Melly bring to the table? What earned him attention on the internet, and what led to a Kanye West co-sign? Frankly, not much more than the occasionally inspired vocal melody, and some ludicrous lyrics (one of the most notable being his demand for “a Lambo with 18 passenger seats” on a diss song directed at PNC Bank). Melly’s second mixtape, We All Shine, is further proof that he still has a ways to go in terms of differentiating himself from the SoundCloud pack; the majority of these 16 tracks are instantly forgettable, with derivative trap production that finds Melly exploiting the exact same warbled choral approach on nearly every song. The only real saving grace comes at about the midway point, with “Mixed Personalities” — the previously alluded to Kanye West-featuring song. Here, playing off of West’s hook, Melly seems like a more interesting artist, switching up his vocal approach in tandem with the unstable emotional arc of the track. When Melly asserts that he will “take the bitch out to Bahamas, let the ho eat at Benihana,” he delivers the line with such frantic energy that one really has no clue whether or not to take it as a romantic gesture or a disturbing threat. That kind of complexity is sorely missed elsewhere here. Paul Attard

Florida crooner YWN Melly is largely concerned with two things: romantic woes and murder. For every “Murder on my Mind” that the 19-year-old pens, he has a couple of banal love ballads in his back pocket. His delivery isn’t anything particularly original; Fetty Wap was doing this sorta mumble rap/canorous moan thing long before Melly turned his homicidal thoughts into a breakthrough. So just what does Melly bring to the table? What earned him attention on the internet, and what led to a Kanye West co-sign? Frankly, not much more than the occasionally inspired vocal melody, and some ludicrous lyrics (one of the most notable being his demand for “a Lambo with 18 passenger seats” on a diss song directed at PNC Bank). Melly’s second mixtape, We All Shine, is further proof that he still has a ways to go in terms of differentiating himself from the SoundCloud pack; the majority of these 16 tracks are instantly forgettable, with derivative trap production that finds Melly exploiting the exact same warbled choral approach on nearly every song. The only real saving grace comes at about the midway point, with “Mixed Personalities” — the previously alluded to Kanye West-featuring song. Here, playing off of West’s hook, Melly seems like a more interesting artist, switching up his vocal approach in tandem with the unstable emotional arc of the track. When Melly asserts that he will “take the bitch out to Bahamas, let the ho eat at Benihana,” he delivers the line with such frantic energy that one really has no clue whether or not to take it as a romantic gesture or a disturbing threat. That kind of complexity is sorely missed elsewhere here. Paul Attard

Sifting through the cultural detritus of a coming-of-age at the turn of the millennium, SBN3’s It’s Not the 90s is, evidently, a sequel to last year’s 2000 on Everything. Soul Bro has expanded on his unique brand of dexterous rapping, rapturous sing-song hooks, and early-aughts fetishizing — while also slimming-down the runtime of this project as compared to the last one. Opener “Ecko Quicksilver” is a trumpet-led anthem that bursts right out of the gate, providing a summary of 2000 on Everything, replete with lighthearted aughts references, and delivered through the filter of a braggadocio typical of modern pop-rap, if slightly skewed (“my bank fatter than season 1 Josh Peck”). The first five tracks go on to establish this set’s aesthetic, which consists of playful wordplay couched in synths and tip-toeing beats. “Hollywood Video” finds SBN3 spitting like Playboi Carti, casually expanding his interest in vocal expression akin to the experimentation of contemporaneous SoundCloud rappers; the line “I get that moment like Kodak” in video game reference-leaden track “Totodile Freestyle” might as well shout-out our man Bill K. Kapri. “Aguilerian Preaching” marks the big shift in the set, taking the generally silly reference point of worship for Christina Aguilera to an absurdist degree, literally preaching the “good word” with utter sincerity (and deftly recalling Jim Morrison on “Horse Latitudes”). “Xtrinity” and “Rolling Letters Red” reiterate this appreciation (“Keep that Christina in your mind”), but it’s “Say La Vee” that proves the zenith of the project. This track features a looped sample of Ms. Aguilera in its instrumental, with a victorious repeated chant of “Say la vee / say la vee / say la vee” amplifying a sense of hope, as if answering the previous track’s downtrodden sentiment of “Your testament was what I knew but what I knew will bring the betterment / all these kids riddled with that Ritalin.” There’s a sense that SBN3 is alleviating childhood pain and confusion through his embrace of cultural artifacts from his youth; where 2000 on Everything’s hilarious, but often clashing, skits might have introduced a subtext of ironic detachment, the seamlessly arranged It’s Not the 90s reiterates the joy underlining both records. The final four tracks, then, constitute a victory lap — and its beats range from Disney soundtrack to Bop It samples. SBN3 redefines the old “One Man’s Trash” adage, but ever on-brand: “That shit’s not Nirvana, it’s The Simple Life.” Joe Biglin

Sifting through the cultural detritus of a coming-of-age at the turn of the millennium, SBN3’s It’s Not the 90s is, evidently, a sequel to last year’s 2000 on Everything. Soul Bro has expanded on his unique brand of dexterous rapping, rapturous sing-song hooks, and early-aughts fetishizing — while also slimming-down the runtime of this project as compared to the last one. Opener “Ecko Quicksilver” is a trumpet-led anthem that bursts right out of the gate, providing a summary of 2000 on Everything, replete with lighthearted aughts references, and delivered through the filter of a braggadocio typical of modern pop-rap, if slightly skewed (“my bank fatter than season 1 Josh Peck”). The first five tracks go on to establish this set’s aesthetic, which consists of playful wordplay couched in synths and tip-toeing beats. “Hollywood Video” finds SBN3 spitting like Playboi Carti, casually expanding his interest in vocal expression akin to the experimentation of contemporaneous SoundCloud rappers; the line “I get that moment like Kodak” in video game reference-leaden track “Totodile Freestyle” might as well shout-out our man Bill K. Kapri. “Aguilerian Preaching” marks the big shift in the set, taking the generally silly reference point of worship for Christina Aguilera to an absurdist degree, literally preaching the “good word” with utter sincerity (and deftly recalling Jim Morrison on “Horse Latitudes”). “Xtrinity” and “Rolling Letters Red” reiterate this appreciation (“Keep that Christina in your mind”), but it’s “Say La Vee” that proves the zenith of the project. This track features a looped sample of Ms. Aguilera in its instrumental, with a victorious repeated chant of “Say la vee / say la vee / say la vee” amplifying a sense of hope, as if answering the previous track’s downtrodden sentiment of “Your testament was what I knew but what I knew will bring the betterment / all these kids riddled with that Ritalin.” There’s a sense that SBN3 is alleviating childhood pain and confusion through his embrace of cultural artifacts from his youth; where 2000 on Everything’s hilarious, but often clashing, skits might have introduced a subtext of ironic detachment, the seamlessly arranged It’s Not the 90s reiterates the joy underlining both records. The final four tracks, then, constitute a victory lap — and its beats range from Disney soundtrack to Bop It samples. SBN3 redefines the old “One Man’s Trash” adage, but ever on-brand: “That shit’s not Nirvana, it’s The Simple Life.” Joe Biglin

There are so few worthy Detroit rap stars these days: You’ve got a complete and utter cornball in Big Sean, who has ambitions of being Kendrick Lamar but possess about a quarter of the talent; Tee Grizzley, whose output has yielded diminishing returns since surprise radio hit “First Day Out”; and of course Eminem, a man who has basically pissed away what little good faith he had left with his last few trash albums. Suffice to say, the city needs new blood — and so, enter Sada Baby, an eccentric (to put it mildly) smack talker from the East side of the city who’s as likely to spit some insane boast (pick your favorite from his latest mixtape, Bartier Bounty, but I’ll go with: “Pull up on your fam, dump my mag in your birthplace”) as he is to break out into some insane dance to out-stunt everyone in the room (“I will do a Harlem Shake with the Draco”). Sada’s appeal is his unpredictability; his rapping is exciting for just how reckless it can get, as he swerves through tracks of energetic bluster (“Skuba Says”), G-funk swagger (“On Gang”), and anger-fueled bravado (“Unkle Drew”). Unfortunately, the rapper’s also prone to missteps: he openly admits at one point that he “ain’t Meek Mill or Drake, nah / But I fuck with both of them,” a sentiment he takes too far when he tries to bite the 6 God’s flow on “Aunty Melody.” He also has a tendency for going a little bit too overboard sometimes, like his distasteful claim that he’s “gettin’ higher than Mac Miller” or that he should be called “Skuba R. Kelly” because his diamonds glisten like urine. But almost always, Sada Baby’s intense charisma and crazed delivery add up to an artist who demands attention. Paul Attard

There are so few worthy Detroit rap stars these days: You’ve got a complete and utter cornball in Big Sean, who has ambitions of being Kendrick Lamar but possess about a quarter of the talent; Tee Grizzley, whose output has yielded diminishing returns since surprise radio hit “First Day Out”; and of course Eminem, a man who has basically pissed away what little good faith he had left with his last few trash albums. Suffice to say, the city needs new blood — and so, enter Sada Baby, an eccentric (to put it mildly) smack talker from the East side of the city who’s as likely to spit some insane boast (pick your favorite from his latest mixtape, Bartier Bounty, but I’ll go with: “Pull up on your fam, dump my mag in your birthplace”) as he is to break out into some insane dance to out-stunt everyone in the room (“I will do a Harlem Shake with the Draco”). Sada’s appeal is his unpredictability; his rapping is exciting for just how reckless it can get, as he swerves through tracks of energetic bluster (“Skuba Says”), G-funk swagger (“On Gang”), and anger-fueled bravado (“Unkle Drew”). Unfortunately, the rapper’s also prone to missteps: he openly admits at one point that he “ain’t Meek Mill or Drake, nah / But I fuck with both of them,” a sentiment he takes too far when he tries to bite the 6 God’s flow on “Aunty Melody.” He also has a tendency for going a little bit too overboard sometimes, like his distasteful claim that he’s “gettin’ higher than Mac Miller” or that he should be called “Skuba R. Kelly” because his diamonds glisten like urine. But almost always, Sada Baby’s intense charisma and crazed delivery add up to an artist who demands attention. Paul Attard

Kicking the Canon | Album Selection

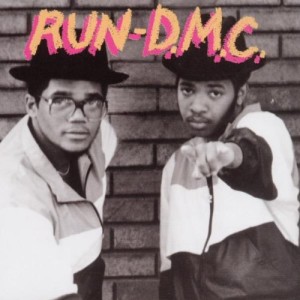

To distinguish between “old-school” hip-hop of the late 1970s and the “new school,” founded primarily by Run-DMC and LL Cool J, listen to Kurtis Blow’s 1980 cut “Hard Times.” Socially-conscious lyricism is underscored by smooth-groove funk; it’s party music, replete with a minute-long bongo solo serving as the bridge. On the other hand, the first track on Run-DMC’s eponymous debut album — also called “Hard Times” — begins with a percussive synth note. It stands as a paroxysm; a call to attention. But in point of fact, this “Hard Times” is a cover of the earlier one — and Joseph “Run” and older brother/manager Russell Simmons both worked for Blow. During that time, Russell was often credited as a co-writer, but little brother Joseph was known to trade bars with Blow, even despite being a high schooler. Combine all of this knowledge with the introduction of a Grandmaster Flash-idolizing Darryl “Easy D” McDaniels, teaching himself to spin records and writing hard-as-fuck lyrics (Russell didn’t approve), and the inimitable DJ Jazzy Jase (Jam Master Jay) — who’d dominate parties at Two-Fifth Park in Hollis, Queens, while rocking the flyest b-boy style — and you have the crew who followed that synth hit with a brand new sound. First, a simple kick drum foundation; then, snare claps, and a sample-or-ad-lib, in time to the drum track. Rick Rubin — founder of Def Jam, out of his NYU dorm room, and early adopter of Run-DMC — would go on to take this stripped down production as his signature sound, though he wouldn’t hear Run-D.M.C. until later. But for those who did hear the 1984 album at the time of its release, from the moment the duo screamed “HARD TIMES!,” that was the moment it became clear that hip-hop would never be the same. No longer a mere party novelty, rap music found its champions in this new school. And with this record, Run-DMC invented the hip-hop album.

To distinguish between “old-school” hip-hop of the late 1970s and the “new school,” founded primarily by Run-DMC and LL Cool J, listen to Kurtis Blow’s 1980 cut “Hard Times.” Socially-conscious lyricism is underscored by smooth-groove funk; it’s party music, replete with a minute-long bongo solo serving as the bridge. On the other hand, the first track on Run-DMC’s eponymous debut album — also called “Hard Times” — begins with a percussive synth note. It stands as a paroxysm; a call to attention. But in point of fact, this “Hard Times” is a cover of the earlier one — and Joseph “Run” and older brother/manager Russell Simmons both worked for Blow. During that time, Russell was often credited as a co-writer, but little brother Joseph was known to trade bars with Blow, even despite being a high schooler. Combine all of this knowledge with the introduction of a Grandmaster Flash-idolizing Darryl “Easy D” McDaniels, teaching himself to spin records and writing hard-as-fuck lyrics (Russell didn’t approve), and the inimitable DJ Jazzy Jase (Jam Master Jay) — who’d dominate parties at Two-Fifth Park in Hollis, Queens, while rocking the flyest b-boy style — and you have the crew who followed that synth hit with a brand new sound. First, a simple kick drum foundation; then, snare claps, and a sample-or-ad-lib, in time to the drum track. Rick Rubin — founder of Def Jam, out of his NYU dorm room, and early adopter of Run-DMC — would go on to take this stripped down production as his signature sound, though he wouldn’t hear Run-D.M.C. until later. But for those who did hear the 1984 album at the time of its release, from the moment the duo screamed “HARD TIMES!,” that was the moment it became clear that hip-hop would never be the same. No longer a mere party novelty, rap music found its champions in this new school. And with this record, Run-DMC invented the hip-hop album.

Slight alterations in ad-libs, like the inclusion of “home-boy” in the bar, “So watch out / Home-boy / Don’t let it catch you” on “Hard Times,” invoke the streets from which Simmons and McDaniels came. Run and DMC trade bars, mid-verse, sometimes alternating words — their upward inflection, and simple wordplay, sometimes being characterized as “cheesy,” but the intense bursts of energy resultant negate this criticism. A later bar, “Because I need that dollar every day of the week,” could be seen as the origin point for the get-the-money ethos that still defines so much of hip-hop to this ay, but that lyric actually comes from Blow’s original 1980 track — which means that, if this is an origin point, its power as such comes more from the specific synergy of Run-DMC’s vocals and instrumentals. The two ‘Kush Groove’ tracks, “Hollis Crew” and “Sucker M.C.s” — particularly the Run-led latter — prototyped all future rap cliches, and positively drip with disses-turned-brags (“I get DEAF as the others turn FAKE!”). The back-and-forth between MCs on “Hollis Crew” serves as a call-and-response; they finish each other’s sentences, or sentiments, and answer each other’s questions. It helps that, tonally, the two rappers compliment each other perfectly.

“Rock Box,” this LP’s masterpiece, finds Run taking ad-lib tradeoffs to extreme ends, all while soaring guitar riffs (played by session musician Eddie Martinez, who also features in the song’s video) solidify a watershed in rap that rocks-the-fuck-out. This genre fusion was never a gimmick for this duo — it was their core ethos. While they would go on to sample Aerosmith’s “Walk this Way,” two LPs down the line, every track here builds something out of nothing, skeletal beats transforming into all-time earworms. The immediacy of 1989’s Raising Hell won most over, but this debut has a rawness that connoisseurs of the modern rap sound (or modern punk rock, for that matter) can appreciate. “It’s Like That,” the game-changing 1983 single, is less a finger-wagging, Reagan-era PSA than a universal document of pain (“I go through life with my glasses blurred”). And the subsequent “Wake Up” strengthens and imbues the concept with the purposeful dispensation of reality: “It was a dream!” This wistfulness gets sublimated into the divinely silly “Monster Mash”-esque synths of “30 Days,” and eventually the album cools off with “Jay’s Game,” a melisma of vocal samples from the album (particularly from Jam Master Jay), before plunderphonics was a thing, and a simple flex of disc-scratching and beat chopping prowess. For those who think rap is all about one formula [beats + lyrics], as the genre is often reduced to, returning to Run-DMC is a humbling reminder that rap’s sound has continually evolved, from the time of its invention (by this trio). Joe Biglin

Comments are closed.