The 48th edition of New Directors/New Films runs March 27th – April 7th. Here’s our first dispatch. Included — very much intentionally — in our second and final dispatch from the fest is a film that isn’t actually playing the fest at all, at least not anymore. The exact reasons as to why that film isn’t playing (its screenings were canceled at the very last minute) are not the stuff of public knowledge at the time of this writing, but consider this: Qiu Sheng’s Suburban Birds is the fourth official selection at a major film festival to have its screenings cancelled, with only vague reasons given as to why, in less than two months time. All four of these films are Chinese productions — the others being Zhang Yimou’s One Second and Derek Tsang’s Better Days at the Berlinale, as well as the twofer of Lou Ye’s The Shadow Play and the accompanying Ma Ying Li film Behind the Dream: A Documentary on the Shadow Play (which we’ll count as one “selection,” to be nice), at the Hong Kong International Film Festival. This is a problem that we don’t want to be party to, so below you’ll find our take on Suburban Birds, a film that we hope others will have the opportunity to see soon. You’ll also find a film offering a further consideration of Chinese censorship (Zhu Shengze’s Present.Perfect), heavily geopolitical films from Serbia (Ognjen Glavonic’s The Load) and Singapore (Yeo Siew Hua’s A Land Imagined), a documentary about citizens taking up the slack of the government through the private sector (Luke Lorentzen’s Midnight Family), and finally, a “Duchampian” contemplation of what even constitutes art anymore (Peter Parlow’s The Plagiarists). ND/NF may have lost the battle, when it comes to Suburban Birds, but thanks to its always-adventurous, probing, and provocative programming, it sure isn’t losing the war.

Update (April 4, 2019): Suburban Birds screenings are back on at ND/NF this weekend, after the film received the proper certificate from Chinese authorities for its foreign release. Learn more over at IndieWire.

The enduring impulse to defamiliarize — that is, to (re-)present something as novel or new — is at the heart of Peter Parlow’s The Plagiarists. Directed from a script by Robin Schavoir and James N. Kienitz Wilkins, this 76-minute feature opens in programmatic, low-budget indie form: a pair of hipster intellectual-artist-types, Anna (Lucy Kaminsky) and her boyfriend Tyler (Eamon Monaghan), have some car trouble on their way back from a friend’s bougie, oft-Airbnb-ed vacation home. In short order, Clip (Michael “Clip” Payne), an older black man from around the neighborhood, offers them some help, and the couple soon find themselves in his home for the evening. As liquor and conversations start to flow, we learn that Anna is a budding novelist writing her first book, while Tyler is an aspiring filmmaker who works mainly as a DP on commercials. Those who might want to take this as a sly send-up of American indie filmmaking pretensions — both in front of and behind the camera — will find much to support that assessment. (Tyler namedrops Dogme 95 at one point, though he can’t remember whether it comes from Denmark or Norway.) And yet, with its particular attention to film/video formats (it was shot on an ‘80s TV-news camera), The Plagiarists reveals itself to be something more maddeningly, if also productively, contradictory. In particular, the film hinges on an extended, eloquent childhood reminiscence from Clip that, Anna discovers months later, was plagiarized in its entirety from Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård. “This is not about art!” Anna exclaims, visibly unsettled by this discovery. And yet it is. (It’s no accident that the snippet we hear of Anna’s novel — not a memoir, she emphasizes — relays the experiences of someone she’d met on a trip to New Guinea.) Bringing in a skein of talking points, including artistic (mis)representation and cultural appropriation, The Plagiarists explores the enduring, Duchampian question of what constitutes art, especially in a content-saturated environment where the notion of the “readymade” feels more fraught than ever. Appropriately, then, this film only becomes knottier — and thereby more interesting — the more one tries to untangle it. Lawrence Garcia

Zhu Shengze’s Present.Perfect. is preceded by information about the state of live-streaming in China, making clear its overwhelming popularity in the country — there were 422 million users (known as “anchors”) in 2017. On June 1st of that year, the Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China came into effect, leading to: data localization, stricter censorship laws, and requirements for anchors to use their real names. There’s a quote from the Cyberspace Administration of P.R. China that’s included in the film, explaining the apparent fear in the homogenization of the real world and the “virtual” world. It establishes what Zhu is trying to accomplish with Present.Perfect: to push back against any negativity surrounding live-streaming and make evident how these platforms are, in fact, providing unflinching portraits of the Chinese population. That many of the anchors are far from the “exemplary” people that a country may want as national representatives (one person has muscular dystrophy, another is a burn victim, one just likes to dance in public spaces) is intentional, with Zhu showing the importance of these streaming platforms in giving everyday people a voice, and exposing others to their lives and stories. This impact is largely felt with the film’s structure, starting with nondescript clips of construction and work life before easing into the “raw” liveblogging videos that Westerners could witness on Twitch IRL, Instagram Live, and the like. At two hours, though, Present.Perfect. is a film whose readily-understood message is outweighed by a novelty that wanes by the minute. While there’s more purpose to this film than, say, a Vine or TikTok compilation video, there’s certainly more enjoyment one can have when viewing actual live videos. Which is to say, there’s little reason to watch this film rather than simply visiting these platforms and experiencing the authenticity for oneself. There’s also less agency here than rifling through YouTube vlogs via the website’s recommendation system, as the act of moving from one video to the next on one’s own time is an act of participation in and of itself. Present.Perfect is thus an insightful film bogged down by its format: the “live” component of the subject matter proves contradictory in cinematic form, and the accessibility of live-streamed material renders the film nearly superfluous. Joshua Minsoo Kim

Zhu Shengze’s Present.Perfect. is preceded by information about the state of live-streaming in China, making clear its overwhelming popularity in the country — there were 422 million users (known as “anchors”) in 2017. On June 1st of that year, the Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China came into effect, leading to: data localization, stricter censorship laws, and requirements for anchors to use their real names. There’s a quote from the Cyberspace Administration of P.R. China that’s included in the film, explaining the apparent fear in the homogenization of the real world and the “virtual” world. It establishes what Zhu is trying to accomplish with Present.Perfect: to push back against any negativity surrounding live-streaming and make evident how these platforms are, in fact, providing unflinching portraits of the Chinese population. That many of the anchors are far from the “exemplary” people that a country may want as national representatives (one person has muscular dystrophy, another is a burn victim, one just likes to dance in public spaces) is intentional, with Zhu showing the importance of these streaming platforms in giving everyday people a voice, and exposing others to their lives and stories. This impact is largely felt with the film’s structure, starting with nondescript clips of construction and work life before easing into the “raw” liveblogging videos that Westerners could witness on Twitch IRL, Instagram Live, and the like. At two hours, though, Present.Perfect. is a film whose readily-understood message is outweighed by a novelty that wanes by the minute. While there’s more purpose to this film than, say, a Vine or TikTok compilation video, there’s certainly more enjoyment one can have when viewing actual live videos. Which is to say, there’s little reason to watch this film rather than simply visiting these platforms and experiencing the authenticity for oneself. There’s also less agency here than rifling through YouTube vlogs via the website’s recommendation system, as the act of moving from one video to the next on one’s own time is an act of participation in and of itself. Present.Perfect is thus an insightful film bogged down by its format: the “live” component of the subject matter proves contradictory in cinematic form, and the accessibility of live-streamed material renders the film nearly superfluous. Joshua Minsoo Kim

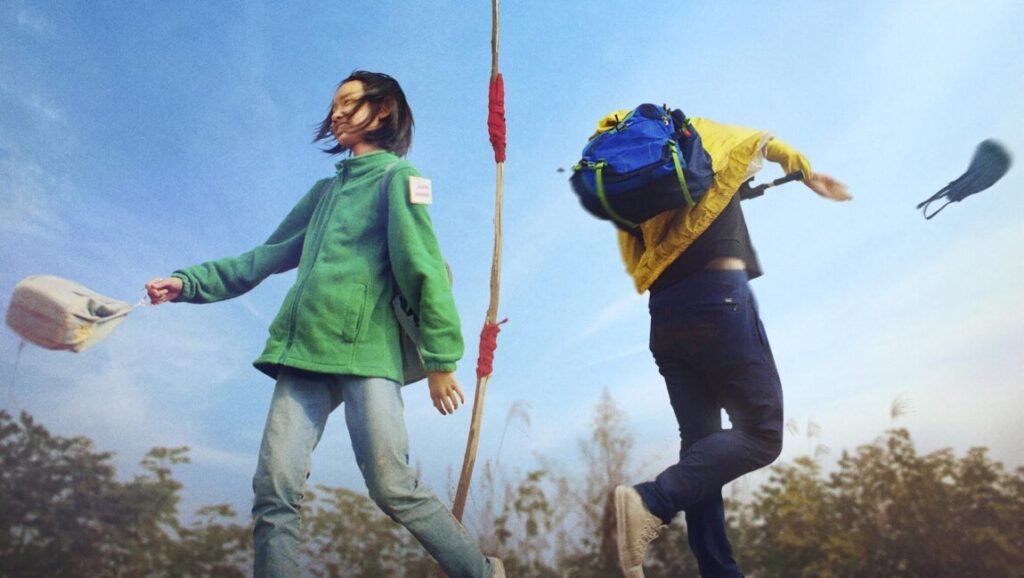

Suburban Birds opens with an iris shot, a formal gesture that likens it to Feng Xiaogang’s recent I Am Not Madame Bovary. Quickly, Qiu Sheng’s film reveals this to be the POV of a land surveyor looking through his theodolite. In its first half, the film is composed mostly of long takes, with constant, horizontal and lateral movements, and zooms, as the camera reacts to characters arriving, leaving, or pointing at something — naturally reminiscent of South Korean filmmaker Hong Sang-soo, especially those zooms. Qiu, a first-time director, does a commendable job precisely controlling the visual field of his film, while his narrative peels back layers of a story that revolves around an investigation of sinking terrain, and the evacuation that the problem causes. In this first half, the totalizing effect of the camera captivates the viewer when the plot doesn’t — but in the middle, things shift. A character starts reading a diary written by a child, and we see that story play-out. A group of school children go on outdoor excursions, chat amongst each other, and tentatively explore their romantic inclinations. Sadly, in this section of the film, the formal qualities of Suburban Birds aren’t nearly as jarring, nor exciting. Though even here, there’s something to the accomplishment of Qiu’s work with child actors, which resonates with a realism akin to some of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s films. As things continue to meander, Qiu’s ambitions expanding with each new passage of his film, these parts don’t quite add-up. Individual moments are clever and amusing, like birds singing referring back to an alarm on a smartphone, or the way the children ironically belt “We’re the Communist Little League of China.” But Suburban Birds is a bit too derivative to be wholly exciting in its own right. Jaime Grijalba

Serbian director Ognjen Glavonic‘s The Load is so minimal and austere that its title – nominally referring to the cargo carried in the truck driven by its protagonist, Vlada (Leon Lucev) – immediately takes on metaphorical meaning. The film’s basic setup — illicit material being transported over dangerous terrain — has been described as an oblique riff on Henri-Georges Cluzot’s 1953 thriller The Wages of Fear. However, Glavonic’s film is, almost perversely, an anti-thriller; long stretches offer little more than observation of the mostly taciturn Vlada grimly navigating the road. The film is set in 1999, during the Balkan wars, as NATO is conducting its bombing campaign against Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. In the midst of this war-torn atmosphere, Vlada is taken to a warehouse in Kosovo and assigned a truck with sealed cargo in the back, the contents of which he’s not allowed to ask about. He’s given strict instructions to go directly, without making stops of any kind, to the drop-off destination in Belgrade. While en route, Vlada immediately encounters a blocked bridge and is forced to make a detour, one which proves a literal manifestation of the film’s main structural conceit: the proceedings largely remain fixed on the protagonist, but veer away from him periodically, with panning shots which briefly follow secondary characters. It’s not until a very late scene that we can guess what Vlada’s been carrying, the clues along the way being so subtle that they’re easy to miss. In fact, the film withholds so much that the vague details Glavonic does offer can easily sail over the heads of viewers not familiar with the history of the 1990s Balkan wars, or the specific war crime referred to here (for that information, you’ll have to go to Glavonic’s 2016 documentary, Depth Two, which gives a fuller description of a context only hinted at in The Load). In the end, plenty of doubts are left as to whether this film has much to say of its own accord — especially as The Load tends to register more with a kind of muted admiration for the filmmaking, rather than elicit the sorrow and outrage that would be demanded of the subject it only alludes to. Christopher Bourne

Serbian director Ognjen Glavonic‘s The Load is so minimal and austere that its title – nominally referring to the cargo carried in the truck driven by its protagonist, Vlada (Leon Lucev) – immediately takes on metaphorical meaning. The film’s basic setup — illicit material being transported over dangerous terrain — has been described as an oblique riff on Henri-Georges Cluzot’s 1953 thriller The Wages of Fear. However, Glavonic’s film is, almost perversely, an anti-thriller; long stretches offer little more than observation of the mostly taciturn Vlada grimly navigating the road. The film is set in 1999, during the Balkan wars, as NATO is conducting its bombing campaign against Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. In the midst of this war-torn atmosphere, Vlada is taken to a warehouse in Kosovo and assigned a truck with sealed cargo in the back, the contents of which he’s not allowed to ask about. He’s given strict instructions to go directly, without making stops of any kind, to the drop-off destination in Belgrade. While en route, Vlada immediately encounters a blocked bridge and is forced to make a detour, one which proves a literal manifestation of the film’s main structural conceit: the proceedings largely remain fixed on the protagonist, but veer away from him periodically, with panning shots which briefly follow secondary characters. It’s not until a very late scene that we can guess what Vlada’s been carrying, the clues along the way being so subtle that they’re easy to miss. In fact, the film withholds so much that the vague details Glavonic does offer can easily sail over the heads of viewers not familiar with the history of the 1990s Balkan wars, or the specific war crime referred to here (for that information, you’ll have to go to Glavonic’s 2016 documentary, Depth Two, which gives a fuller description of a context only hinted at in The Load). In the end, plenty of doubts are left as to whether this film has much to say of its own accord — especially as The Load tends to register more with a kind of muted admiration for the filmmaking, rather than elicit the sorrow and outrage that would be demanded of the subject it only alludes to. Christopher Bourne

The titular ‘land’ that’s ‘imagined’ in Yeo Siew Hua’s Golden Leopard-winning debut film manifests in two different ways, one explicitly physical (the ever-expanding continent of Singapore, forged through migrant labor via land reclamation) and one virtual (the online-generated ‘worlds’ that serve as a home for a globalized community). This suggests that Yeo’s film is one that interacts with its central political allegory on a philosophical level, where concerns of continental proliferation include a strong emphasis on dehumanization — and for about half of its runtime, A Land Imagined attempts to formulate such a multi-faceted critique. The twisty neo-noir uses the disappearance of a Chinese worker, Wang (Liu Xiaoyi), as its framing device and thematic starting point. This seemingly random event that nobody pays much attention to comes to represent the harsh reality of many foreign laborers – if you were to suddenly vanish one day, you can easily be replaced by five other migratory hirelings. In flashbacks, we see Wang coping with his hopeless existence by frequenting the eLover Cybercafe, a 24-hour den of Counter-Strike tournaments and despair. It’s here where Yeo reaches for something profound, linking the two distant realms — one fiction and one reality, both constructed inorganically — together through the lens of endless development and a rapid abandonment of individuality. But this also proves to be where Yeo’s critique skews incoherent, as he throws an inspidly spiritual twist into his missing-person mystery that weakens A Land Imagined’s overarching commentary in favor of less ambitious genre conventions. Paul Attard

There are fewer than 45 government-funded emergency ambulances in Mexico City — far from the sufficient number of vehicles needed to provide for the capital city’s nine million residents. This inadequacy has resulted in private, family-run businesses providing the same service, one of which is operated by the Ochoa family. Luke Lorentzen’s Midnight Family follows the Ochoas and, in the process, underlines issues plaguing the country’s healthcare system. The situation is dire: it takes 40 minutes for a boy with a gunshot wound to get an ambulance. More than simply prove the need for timely healthcare provisions, though, Midnight Family points to how for-profit healthcare can be disastrous. When the Ochoas help a highschool girl physically abused by her boyfriend, the girl almost immediately asks a question regarding the cost of her care, serving as a grim reminder that emergency treatment is something people are willing to forgo due to the price tag. And when the girl’s family is unable to pay, the Ochoas work through another night without compensation. They’re happy to have helped someone, of course, but they’re upset with the outcome. An early scene depicts the family’s home life, and reveals their unstable financial situation, a threat made all the more evident from their language, the tone of their voices, and their actions throughout the film. As such, Midnight Family’s consistent tension relies on two crucial components: both the urgency that defines the life of an EMT and the urgent struggle to resolve financial instability. In one of the film’s most painful sequences, police officers threaten to arrest the Ochoas for “stealing” the ‘bodies’ in their ambulance, a twofold frustration given that this interrogation not only prolongs the trip to the hospital, but also means the family could lose-out on this much-needed money. Midnight Family is consequently at its most compelling when it makes inextricable a link between the Ochoas’ morals and the government’s failed healthcare system — everything seems broken, and everyone just wants to survive. JMK

Comments are closed.