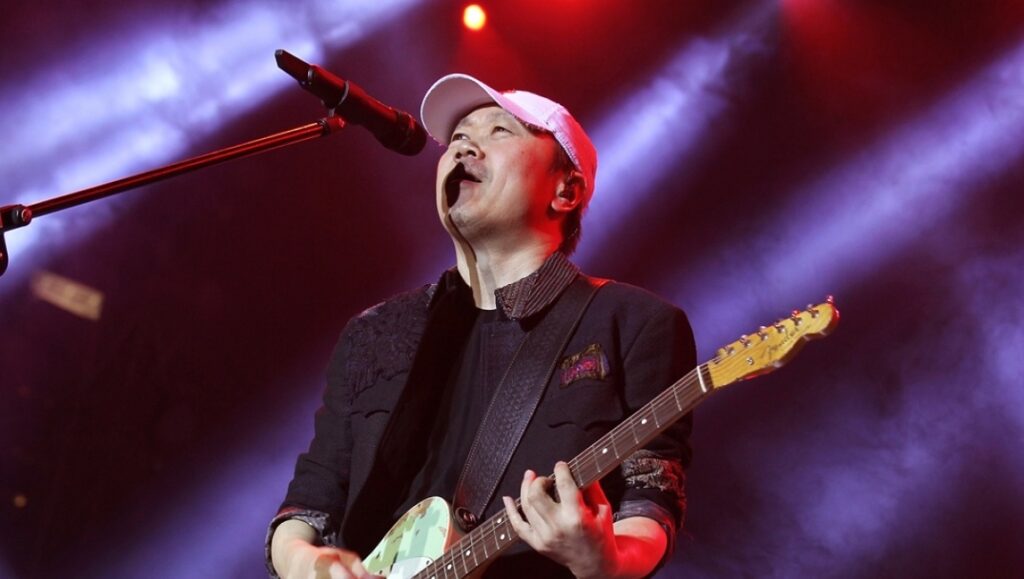

Was it when Elvis first suggestively gyrated his hips on national television? The first time a fan let out a piercing, adulatory scream as the Beatles sauntered by? Or was it further back than all that — the moment that Sister Rosetta Thorpe first picked up a guitar? There’s no true consensus as to when rock ’n’ roll really started — not in the West, anyway. In the People’s Republic of China, however, there’s a much smaller window of time during which one could pinpoint rock’s rise: The Party’s suppression of western culture through the formative years of popular music’s development makes it hard to imagine a Chinese rock (or yaogun, as it’s called) that could exist much before 1982, the year when the country underwent massive economic reforms. And when it comes to this 1980s period, there was no more important figure in Chinese music than Cui Jian, a man nicknamed “The Father of Chinese Rock.” Ethnically Korean, Cui comes from a musical background (his father was a professional trumpeter). He joined the Beijing Philharmonic Orchestra when he was still a teen, but when the classic rock of the West started to filter into the Chinese consciousness, Cui was an early adopter, forming one of the first bands to play western pop in China: ADO, with Hungarian bassist Kassai Balazs, Madagascan guitarist Eddie Randriamampionona, saxophonist Liu Yuan, and percussionist Zhang Yongguang. However, it wasn’t until pursuing a solo career (albeit with mostly the same band) that Cui became a major star. More specifically, it was in 1986, at a commemorative concert at Beijing’s Workers’ Stadium, when Cui donned peasant clothes and performed “Nothing to My Name” — a performance that is now widely regarded as, and remembered for, the debut of ‘China’s first rock song.’

A voice that ubiquitous can’t really be silenced — and as increasingly eroded resistance to the popular music Cui pioneered can attests, Rock ’n’ Roll on the New Long March did help to bring about at least one revolution in China.

The recording of “Nothing to My Name” from Cui Jian’s debut album, 1989’s Rock ’n’ Roll on the New Long March, begins slow and spare, with a sustained synthesizer chord, light percussion, and circular strumming. It’s a love song (“I want to give you my dreams”), but for Chinese youths in the 1980s, emboldened by the rolling-back of Maoism, Cui’s lyrics had political intent. As Cui sings, “But you always laugh at me for having nothing,” multi-tracked vocals, snare with generous reverb, and dizi — a high, whining Chinese flute — bolster the mix. The composition of “Nothing to My Name,” then — the gradual accumulation — becomes integral to its empowering message, and even more so as the song’s tempo quickens and Cui barrels through the final, ecstatic verses, following an atypical, searing solo from Liu Yuan, played on the traditional suona. The lyrics (“The ground beneath my feet is moving”) also proved to be prescient: “Nothing to My Name” was adopted as the anthem of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. For many, this is Cui’s greatest legacy, one essentially of defeat — a time capsule for a fleeting moment when China believed in freedom. In the wake of Tiananmen, Cui’s career struggled; he was barred from performing in China, and his new music was monitored closely by authorities. But there’s another Cui Jian narrative, and this album provides its foundation. My own first experience with Chinese rock, during the years I lived in China, was at a small bar: A man with an acoustic guitar, perched on a stool, strummed the lilting chords of Cui’s “Greenhouse Girl.” The song’s melody has never left me — and as it turns out, I’m not alone. While the Chinese government successfully prevented Cui from performing at any large venues for almost two decades (his ban was finally lifted in 2005), all over China, the indelible melodies of “Nothing to My Name,” “Greenhouse Girl,” “No More Disguises,” and many of his later songs are widely recognized. A voice that ubiquitous can’t really be silenced — and as increasingly eroded resistance to the popular music Cui pioneered can attest, Rock ’n’ Roll on the New Long March did help bring about at least one revolution in China.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.