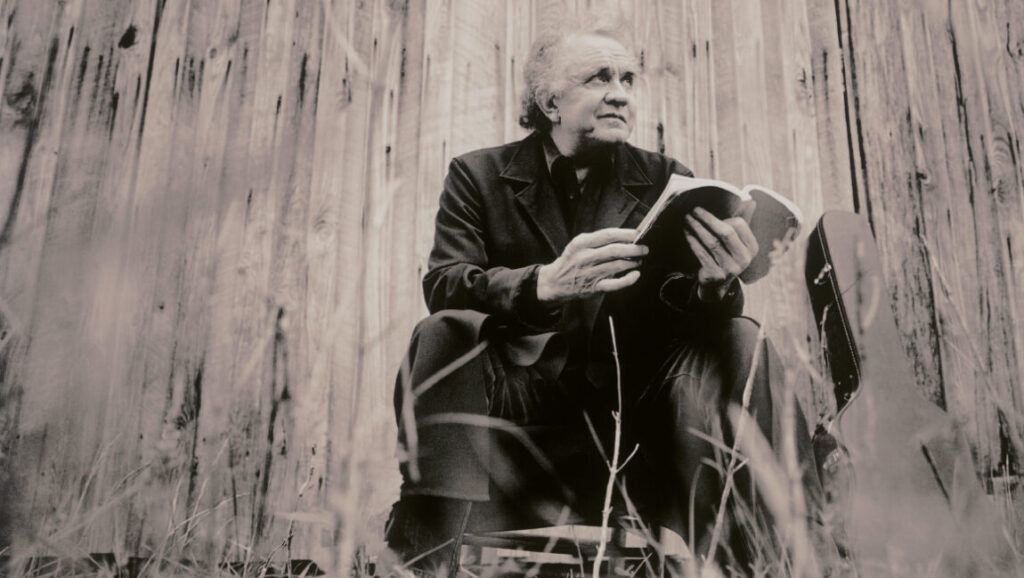

Nobody denies that Johnny Cash was a legend; his mythos looms large in Ken Burns’s Country Music documentary, as good a bellwether as any for how Cash remains one of the genre’s defining personalities. On what foundation does his legacy truly rest, though? For decades, the Man in Black was distinguished by his pitiless outlaw persona, his hell-raising origin story, and the addictive Tennessee two-step he perfected in early sessions for Sun Records and beyond. All of that remains an immutable part of Johnny Cash lore, yet for younger generations, the bulk of Cash’s reputation rests on 1994’s American Recordings, the first in what would become a series of austere collaborations with producer Rick Rubin. The album’s backstory has itself become a kind of cliche; on the downward slope of his commercial and creative prime, and all but forgotten by country radio, Cash holed up in his rustic cabin with nothing more than an acoustic guitar and some simple recording equipment. Rubin may or may not have influenced Cash’s selection of material, but the great reducer doesn’t leave fingerprints anywhere on the recordings themselves, stark and simple and unadorned. If that backstory has been told to death, the album’s influence probably can’t be extolled quite enough: American Recordings may not have invented the back-to-basics ethos, but it certainly embodies it, and it casts a shadow over bedroom indie pop, the less-is-more approach of alt-country, even the unvarnished roots music productions of Joe Henry and T-Bone Burnett.

Very much intentional in its own myth-making: A number of songs look back on wasted youth and hard living, surveying the past with equal parts rue and self-assurance.

At the time of its release, American Recordings ratified Cash’s image as someone who did things on his own terms, devoted to the song and unwilling to compromise to commercial interests; he’d long been abandoned by the country mainstream, but now shrugged his shoulders and acted like he didn’t give a fuck, a gesture that defined him for a new generation of fans in much the same way his Folsom Prison set personified him earlier on. Cash and Rubin would go on to make additional albums in their American Recordings series, some of them literally recorded from the singer’s deathbed; all of the albums have their moments, even some of the death-fetishizing later editions, but none are as faultless as this first volume, which finds Cash still on’ry, authoritative, and in robust voice. He opens the album with “Delia’s Gone,” a traditional murder ballad that’s been recorded ad nauseam but has rarely sounded as hardscrabble or as unsparing as it does here. Cash takes a transformative approach to songs by iconoclasts like Leonard Cohen (“Bird on a Wire”) and Tom Waits (“Down There by the Train”), sanding away artier edges into straight-laced cowboy poetry. By no means is this black-and-white recording devoid of liveliness or humor, either; the straight-man reading of Loudon Wainwright’s “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry” is a deadpan masterpiece, and there’s obvious relish in how Cash takes the contours of “Tennessee Stud.” American Recordings is an album that’s very much intentional in its own myth-making: A number of songs look back on wasted youth and hard living, surveying the past with equal parts rue and self-assurance. The pinnacle is “The Beast in Me,” a moment of sobering introspection penned for Cash by his one-time son-in-law, Nick Lowe; a song that peels back the tall tales and finds behind them a man of endlessly relatable regret and contrition.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.