Falling

The prospect of spending a couple hours with one of the most tremendously unpleasant movie characters you’re likely to ever encounter might not even be the first reason to check out of Viggo Mortensen’s Falling, but it’s certainly the most apparent. This clearly personal story, written and directed by and starring Mortensen, finds his character John grappling with the likely imminent death and deepening dementia of his father Willis, a loud, obnoxious, bigoted, abusive misogynist played in his twilight years by a terrific Lance Henriksen. You will not like this guy.

To its credit, Mortensen’s film makes no real effort to excuse Willis or sugarcoat his behavior with empty sentiment; there are precious few sunbeams of tenderness piercing through to help you feel bad for him. Instead, he relentlessly insults his gay son and son-in-law (Terry Chen), his daughter (Laura Linney), and his biological grandchildren (who appropriately despise him). His only slivers of warmth seem reserved for John’s young adopted daughter, Monica (Gabby Velis), and then only because she seems to regard him more as a curiosity than a threat. His relationship with Monica stands in stark contrast to the ones he shared with his own children in their youth, as evidenced by the increasingly ugly parenting work detailed, often impressionistically, in flashback.

Falling also makes no real effort here to pathologize Willis. He’s not someone who was formed into a monster, but is treated rather an entity unto himself. There are glimpses of past hurt, but the film is careful to avoid any pat psychological explanation for his behavior. Mortensen’s focus, unsurprisingly, is fixed on the two lead performances, and indeed the film is acutely acted for the most part. Though John appears to have the patience of Job when it comes to his old man, Mortensen never misses a little sigh or exasperated inflection in his voice; this man will never get over the pain his father has caused and continues to cause him, and it’s very apparently a struggle for him to keep hold on what little love he can muster, even if it exists only out of a sense of sheer filial duty. Meanwhile, Henriksen has long deserved a big, juicy role like this. He’s not above hamming it up, and his delight in the part seeps into Willis, bringing a vicious glimmer of glee to his endless invective. Deep down he enjoys hurting people because it’s the only thing that soothes his constant anger.

Mortensen, in his first effort behind the camera, proves to be an unflashy director, and that’s fine for his simple goals. True to his on-screen persona as a sort-of “soulful” guy with a hobby of amateur but experienced photography, the film is peppered with vaguely Malickian nature tableaux, a harmonious contrast to the misery that not only threatens to blow this family away, but that, as a lifelong farmer, Willis has idealized — inappropriately, but still — as a symbol of his independence and masculinity. It’s not unreasonable that viewers would bail on this — and many will — as they are given no reason to care about this nasty, incorrigible prick or his put-upon son, but in resisting the maudlin arc so clearly available to the material, Falling’s unfailing earnestness and emotional simplicity become more features than bugs. Matt Lynch

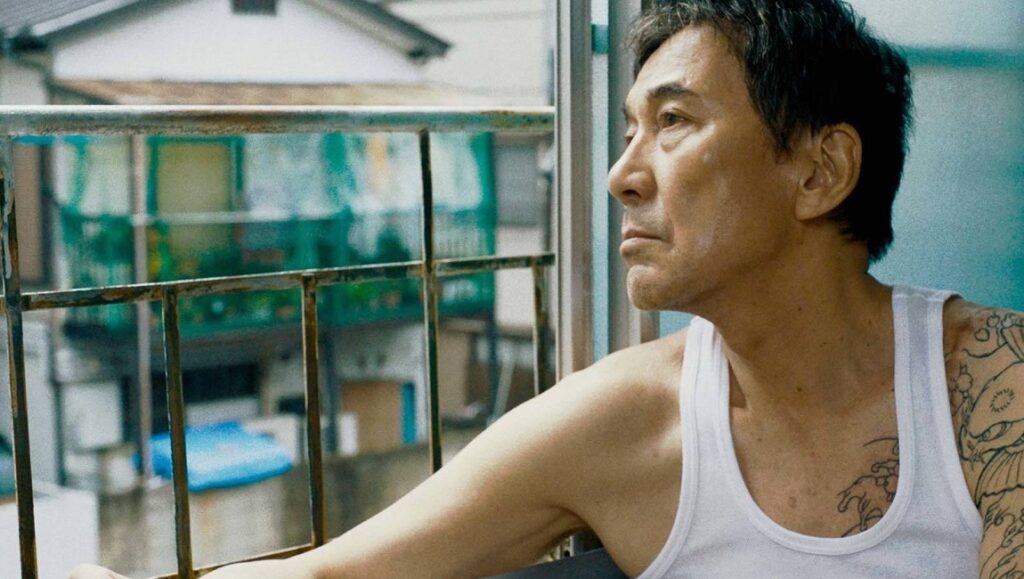

Under the Open Sky

Like R.W. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, Under the Open Sky opens with an aging man being released from prison after serving thirteen years for murder. During his out-processing, the warden glances through the records and, in perhaps an attempt to relieve their unhappy burden, asks if he feels any remorse over them. The man nods, then clarifies his position — not towards the victim, a common “hoodlum” in his words, but for having suffered because of him. Mikami, ex-yakuza and an unloved social outcast played by veteran actor Kōji Yakusho, has vowed to “go straight” ever since, eagerly rejecting the destiny his orphaned childhood and criminal adolescence might have imposed upon him. But the comparisons to Fassbinder’s sprawling adaptation end here: While Mikami’s infantile disposition, imbued with a gruff and childlike innocence, may resemble Fassbinder’s Franz Biberkopf, the trials and tribulations the two encounter in the civilian world bear few similarities: Biberkopf, a common man, undergoes a hellish descent into madness; Mikami, of the underworld, falls a good many times before suddenly picking himself up.

Miwa Nishikawa’s adaptation of Ryozo Saki’s prizewinning novel, Mibuncho, might not have been dealt the fairest hand by being compared to Berlin Alexanderplatz, at less than a seventh of the latter’s colossal scope and runtime. But comparisons aside, Under the Open Sky still proves an increasingly melodramatic work whose quirky sentimentality, masquerading as endearing complexity, seems destined to win over more hearts than minds. From the outset, Nishikawa’s vision for her protagonist’s surroundings is set in stone: society as a whole may prefer not to reintegrate its transgressors, but everyday pockets of humanity usually respond kindly to those who are genuinely interested in rehabilitating themselves. And so begins Mikami’s upward struggle toward a normal life never known to him — he meets an affable lawyer who sponsors ex-convicts as a hobby, then tries leaving behind welfare and landing a job, getting back his driving license, and finding his mother with the help of a television crew. The inability to temper his angry outbursts, however, sees him rejecting the kindness of strangers, roughing up petty gangsters to within an inch of death, etc. — the hallmark of recidivism, essentially. Yakusho, valiantly injecting earnesty and vigour into his character’s rebirth, remains frustratingly subjected to the film’s saccharine generics. More a tiresome collection of calculated emotional investments than an organically developed storyline, Under the Open Sky initially charts a hopeful path, before going astray towards a checklisted, by-the-book formula and nosediving into an inexplicable and unsolicited denouement. There’re only so many bumbling, unhinged, self-pitying tales the genre can take. Morris Yang

Gaza Mon Amour

Arab and Tarzan Nasser’s finely-crafted romance, Gaza Mon Amour, invokes the sensibilities of a fairy tale as a means to cultivate grand gestures of sentimentality, aided by orchestral cues and sweeping wide shots — akin to the early romanticism of melodrama — and thus clearly defines the film’s trajectory. Issa (Salim Dau), a fisherman whose nightly trips into the IDF-surveilled and quartered Mediterranean allow for a consistent livelihood, falls quietly in love with seamstress Siham (Haim Abbass). His steady attempts to court her are disrupted by the very sudden and mysterious accident of fishing an ancient statue out of the sea. From here, Issa’s romantic pursuits become unfortunately complicated by bureaucratic meddling, as knowledge of the statue’s recovery places Issa directly within the State’s crosshairs. Unfurling from this intimate chaos is the patient monotony of day-to-day fatigue, as well as the more specific, locational exhaustion of being situated between repressive governance and oppressive occupation.

The Nassers’ emphasize a clear dissonance between the film’s early romantic idyll and its geopolitical circumstance, and, from a western perspective, it’s the most evocative element at play. Gaza gradually distills its clear conflicting sensory elements — the utopian ideation of emigration and always-encroaching violence — into a kind of realism, morphing these dimensions of lived-in perspective into the shape of cinema: specifically, the seduction of escapism and the amorous banalities that follow this kind of tale. Of course, this reconfiguration is firmly rooted in what is a perpetually imposing environment, pressurized and inescapable, but gleefully ignored within the familiar beauty of a love. All of this is filtered through a longing for the quotidian to expand into something more, where tribulation can be transformed into mere absurdity, and where lovers can laugh in the face of such painful realities; in their version of a love story, the Nassers’ use cinema’s ability to abstract rather than reflect. Gaza Mon Amour is a title that rightfully recalls Resnais’ meditation on trauma and memory, but where he and Duras sought the irreconcilability of identity under war’s residue, the Nassers emphasize the present moment and the way images, beautiful and otherwise, ferment under occupation. Zachary Goldkind

Beans

It wouldn’t be a film festival without the requisite, ham-fisted coming-of-age drama, and for the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival, Tracey Deer‘s Beans comfortably fits the bill. Set during the 1990 Mohawk uprising in Quebec, the film follows an Indigenous twelve-year-old girl nicknamed Beans (Kiawentiio Tarbell) who is caught in the middle of a conflict between descendants of white settlers and the First Nations people who are protesting their sacred land being bulldozed for a golf course. As the uprising turns violent, Beans is forced to navigate her dangerous newfound reality with her father on the front lines, while simultaneously getting caught up with a new group of friends, forcing her to grow up all too quickly.

Despite its timely subject matter, the coming-of-age story at the core of Beans feels distinctly too familiar, relying on tired tropes of adolescent rites of passage set against a revolutionary backdrop. And while there are parallels between the Indigenous uprisings in Quebec in 1990 and current anti-fascist actions happening around the world — the crisis at Standing Rock is an obvious comparison, but the film’s spiritual center easily extends to include Black Lives Matter protests, among others movements — Beans is often marred by an anemic script, amateur performances, and Deer’s awkward sense of pacing. The film even bungles its attempts to establish rapport between characters early on by relying on hyperbolic laughter to punctuate even the most mundane actions, an ungainly attempt to establish contrast with the vile displays of racism and violence that they will all face by the end. Unfortunately, these make very little impact because of Deer’s use of news footage from the time, the harrowing immediacy of which outshines the comparatively stiff reenactments.

Beans certainly has its heart in the right place, offering a fly-on-the-wall look at Native struggles in the face of institutional colonialism, but it displays neither the polish nor the dramatic bonafides to pull off such a serious topic. Even more egregious, Deer fails to make her characters either charming or memorable, a fatal error for a coming-of-age narrative attempting to use a child’s point of view to guide audiences through a historical event. The results are oddly listless and dramatically inert, leaving the unfortunate impression that the Mohawk uprising and its enduring legacy deserve a film that offers more than good intentions. Mattie Lucas

Comments are closed.