La Belle Èpoque is superficial at best, and an endless string of clichés at worst.

Time travel is a popular mechanism throughout film history for understandable reasons: it offers fertile emotional and psychological territory, accommodating narratives that explore universal desires to rejuvenate, revisit, or relive. It’s an appropriate assessment of La Belle Èpoque, where 41-year-old French director-screenwriter Nicolas Bedos tells the story of depressed, stagnated sexagenarian cartoonist and book illustrator Victor (Daniel Auteuil), a man who doesn’t seem able to accept the shifting developments of modern-day life. Unlike his cold and distant wife Marianne (Fanny Ardant), who spends her leisure time attached to VR goggles and internet-surfing, he’s an old-fashioned man who stubbornly mocks technology and is struggling with aging. That is until one day when, through a mysterious agency’s services, he decides not just to relive his past, specifically when he first met young Marianne in 1974, but more importantly to re-stage and recreate it. It’s a plot device that foreshadows La Belle Èpoque’s meta-filmic aspect, exploring the relationship between the real and the imaginary and the notion of role-playing in one’s life, and leads to the film’s fundamental question of the possibility of rewinding time and reviving that which is long-passed. It’s the latter that leads to the most interesting element of Bedos’s film, as unplanned moments complicated Victor’s attempt to re-script and re-stage lived experience according to his memories.

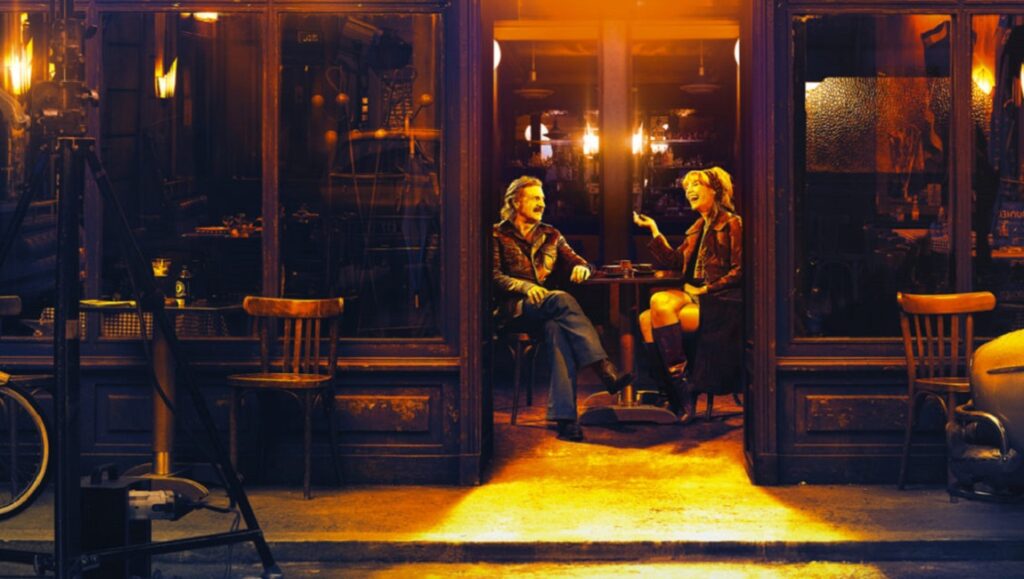

As Bedos explores this particular thread, it’s easy to see thematic similarities with films like The Truman Show, Midnight in Paris, any number of Charlie Kaufman efforts, or even Westworld. It seems likely that this was supposed to work as a remarriage comedy of sorts, but instead of moving into any humorous exploration of the underlayers of the human condition, Bedos presents everything a bit like an outdated vaudeville-esque show. It’s an amalgam that ponderously functions on mere conceptualization, all clichéd plot twists and gimmicks and shallow, happy-go-lucky nostalgia. He fixes his mostly grim-faced characters within the film’s flamboyant visuals — mimicking the work of Jean-Pierre Jeunet with overexposed artificial colors and lighting — where images lose power as they accumulate one upon another and featuring whiplash editing that mechanically cuts from one scene to the next. It’s all in favor of the film’s narrative machinery and whimsy, and Bedos fails to provide any space for delicate moments to bloom or character depth to build. Fake, talkative, and coward are among some of the harsh adjectives Marianne uses to describe her husband, and while it may not be entirely fitting to appropriate these terms as critiques of La Belle Èpoque, it’s fair to say that it’s a fairly regressive film that flirts with a lot of superficial signifiers without managing to develop much emotion or present viewers with any kind of refreshing, singular world. Put simply, Bedos may be content to repeat favored tropes from cinema past, but viewers deserve something more creative and innovative from his next effort.

Published as part of Before We Vanish | October 2020.

Comments are closed.