The Tsugua Diaries

The Tsugua Diaries would be considered quite the swing for most any other director, but for Miguel Gomes, here partnered with documentarian and collaborator Maureen Fazendeiro, it’s a relatively low-key effort, a “romp” even for a director whose last outing was a massive, three-part adaptation of Arabian Nights. Ethnography, self-reflexive gestures, nested narratives, equally baroque and juvenile humor, Gomes’s is a cinema whose density is offset by choice moments of accessibility, but this newest film — something of a pandemic-encouraged time-killer while he continues work on Selvajaria — maintains its otherwise impressive meditativeness so much so that the film grows nigh-impenetrable, mostly bereft of the sorts of metacinematic gestures that hoisted films prior above potential somnambulism.

Still, the film begins within the familiar unfamiliarity that Gomes is so adept at disposing audiences toward: we open with the title card of “Day 22,” clinching the diarisim of the title, and a casual dance party between friends, set to Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons’ “The Night” (whose presence isn’t unlike the use of the cover of “Be My Baby” in 2012’s Tabu), that then evolves into some dreaded pairing off. When the next title card reads “Day 21”, it’s made clear that The Tsugua Diaries’ vignettes are moving in reverse chronological order, a decision so representative of Gomes’s artistry that any sort of surprise is mostly fleeting. Talk of planning the just-glimpsed party occurs between three friends (Carloto Cotta, Crista Alfaiate and João Nunes Monteiro), who possess a relaxed chemistry, afforded to them by their shared work of constructing an outdoor greenhouse for their butterflies. The camera occasionally acts as a taxonomic tool, settling on rotting fruit, wooden beams, the insects themselves; as rendered in the understated color palette, these images are as ravishing as anything in the black-and-white Tabu.

Then, something strange happens, as if the film were slipping away from its established conceit. Dialogue begins to repeat, though delivered by different characters, and unfamiliar faces begin to crop up. Suddenly, it’s the film set for the threeway character study that was presented initially, a distinction not only made clear by all the various tools of the trade strewn about, but the sudden prevalence of mask-wearing as well. The fiction can’t sustain the abstract threat of coronavirus, and instead decides to opt for direct acknowledgement. The film crew is a microcosm of pandemic responses, with quarantine and masking regulations shirked (by the devilishly good-looking Cotta), and the subsequent risks weighed by the more pragmatic actors and technicians. If you abscond to go surfing unannounced, of course the person you’re supposed to kiss in the day’s scene is going to be nervous!

Gomes himself appears in Tsugua Diaries — yet another one of the director’s sly metacinematic tricks (Arabian Nights opens with him running from the production) — which confirms his early press statement that the film is part lockdown journal, part fiction. How these two filmmaking modes are supposed to interact, however, is fairly circumscribed by the unhurried structure. Routine is easily internalized, and the visual prettiness buoys much of what transpires, even if it’s just minute on-set frustrations. There’s simply not enough distance though, unlike Tabu’s stark bifurcation or the stacked fairy tales of Arabian Nights. In swinging for the contemporaneous, Gomes sacrifices his own adventurousness, the entity of the pandemic halfheartedly slapped atop a movie “about” movies.

Writer: Patrick Preziosi

The Crusade

One of the more consistently interesting young(ish) actors working in international cinema, Louis Garrel has also spent the last decade working at a less interesting directing career which, so far, has mostly resulted in films indistinguishable from his father’s contemporary pictures (2015’s Les Deux Amis the most egregious permutation of this homage/mimicry). But as the senior Garrel passively sinks deeper into self-parody with each new picture, Louis’ films have begun to consciously embrace this angle, still working within similar narrative frameworks, but with a nimbler sense of self-deprecating humor. His 2018 feature, A Faithful Man, while not totally free of the Garrelian tendency towards male chauvinism, was at least a spry, funny film (something that his work had thusly evaded), qualities his latest film, The Crusade, embraces more fully and with lively results.

A sort of sequel to A Faithful Man, and once again co-scripted by Garrel with the late Jean-Claude Carrière (quite possibly his final screenwriting credit), The Crusade is written in the mold of the social satire for which the latter writer was best known. Veering away from the romantic melodrama of the first film, this one returns its focus to bourgeois couple, Abel and Marianne (Laetitia Casta and Louis once again), and their 13-year-old son Joseph (Joseph Engel, also returning from the previous film), who has since become an integral member of an international coalition of ethnically diverse teenagers, having aligned with the mission of solving Africa’s water crisis. An immediately more exciting narrative than what Garrel and Carrière previously cooked up together, The Crusade also benefits from tight scripting, taking its time to reveal its full scope, beginning with mundane conflict that quickly erupts into massive philosophical turmoil on a global scale. Seemingly inspired by Greta Thunberg (one of the characters literally watches her U.N. speech), Joseph and his young comrades decide to take direct action to resolve the threat of climate change and resulting resource scarcities, funding their project by selling off the frivolous excesses of their parents’ wealth (i.e. artwork, jewelry). Initially irate (Garrel and Casta are immediately hilarious, shrieking about vintage Dior and rare book appraisals) the couple is soon split on how best to proceed: Marianne is empathetic to the cause and impressed by their son’s initiative, while Abel resorts to defensiveness, championing the status quo. Garrel’s commitment to his character’s heel turn is commendable (and better still, quite funny), gleefully performing a gauche conservatism contrary to the leftist idealism of his character in 2005’s Regular Lovers, where he acted as a sort of analog for his father circa May ’68. It’s worth considering The Crusade in relation to that film’s depiction of a political youth movement and the larger Garrel cinematic legacy: In contrast to the previous film, this one addresses the present directly, which suggests a complacency in Garrel’s generation that must be corrected for by those now coming of age.

The Crusade isn’t without its flaws: the notion of a bunch of French entangling themselves in the business of various African Governments is obviously a dubious one (some expository dialogue about government approval clearly written to sidestep this issue notwithstanding), and there’s a romanticism to the proceedings akin to that of Regular Lovers, albeit scaled down to being age appropriate for this 13-17 age group (plays like Moonrise Kingdom, very uncomfortable, very French). These are signs that Garrel hasn’t completely transcended his dumber macho instincts — and to be honest, it’s hard to imagine those will ever entirely vanish from his work — but The Crusade’s screenplay tips its scales in favor of humility and generosity, and its 67 minute runtime keeping the action moving at a steady clip. Surprising and meaningfully engaged with the contemporary, this really might indicate the start of a significant new phase for Louis Garrel as filmmaker.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Clara Sola

The debut feature of Costa Rican-Swedish director Nathalie Álvarez Mesén neatly lays its cards out in the opening shot. The titular Clara, a woman of middle age with dark hair and a piercing gaze, stands facing an unbridled white stallion, urging it to approach her. A wide shot reveals that it is her, and not the animal, who is fenced in, seemingly unable to cross past an invisible barrier marked off by some posts — she stretches her arm forward but cannot get close enough to touch it while the horse blithely idles away, free to come and go at will. The symbolism imbued in this moment expresses the focus of Clara Sola, a film about a woman’s struggle to liberate herself from the oft invisible bonds of patriarchal tradition. Álvarez Mesén, whose background includes a B.F.A. in Mime, has made an inspired casting selection in professional dancer Wendy Chinchilla Araya to play her lead. The film shines brightest in following these performance art instincts, capturing the instinctual physicality and gutting ferocity of Chinchilla Araya’s performance, which buoys the work against the downpour of symbolism threatening to capsize it.

Set in a small Costa Rican village, Clara Sola traces the lives of a three-person family unit, Clara, her domineering mother Fresia, and her niece Maria. While the dynamic between the three women at first appears typical, we are gradually introduced to the oddities of Clara’s stunted social development as she is infantilized by her mother who further pushes her into the role of a healer in the village, considered blessed by and in direct contact with the Virgin Mary. Further complicating the situation, we learn that Clara suffers from painful scoliosis — necessitating a surgery that Fresia refuses to allow — requiring her to wear a corset, which doubles as a metaphor for the rigid traditions which straitjacket her burgeoning sexuality. This immediate tension is externalized in Maria’s boyfriend Santiago, whose presence begins to shake up the stiff structure of Clara’s life. Meanwhile, parallels are drawn between her and Maria, whose quinceañera forms the focal point of the film’s climax, at once stressing the separate worlds between the aunt and her niece as well as highlighting how subtle variants of this repressive extreme permeate into acceptable traditions and norms.

Visually, we are treated to an array of intimate close-ups, with DP Sophie Winqvist Loggins (who filmed last year’s Cannes selection Pleasure) pulling striking beauty from the simplest shots. One of the most memorable is the simple framing of two pairs of hands belonging to Clara and Maria, rising up into the frame one-by-one, until Maria’s hands withdraw and Clara’s stay aloft, alone. In a later scene, Clara and Santiago sit inside his truck tracing raindrops rolling down the windshield in a makeshift race, the camera lingering on their faces awash with the playfulness of the moment. At other times, the poetic symbolism becomes too heavy-handed, the appearance and disappearance of the unruly horse Yuca, whose fate Clara sees as entwined with her own, is later mirrored by a green beetle she captures to keep with her, or elsewhere the murky fish tank centered in the room, more animals trapped within bounds they cannot control. Even the plants serve as metaphors, like the touch-me-nots, which close up quickly at that touch and, like Clara, “take ages to open.”

But however blunt much of the symbolism is, the film’s strength comes from the raw and enigmatic Chinchilla Araya, who captures Clara’s duality — at times meek and desperate for a semblance of human connection, and at others displaying an unfettered command of her powers. Her performance is paired alongside probing questions of religious dogma and patriarchal gender roles, and the combination calls to mind Satyajit Ray’s delicate yet forceful handling of similar subject matter in Devi, wherein the wonderful Sharmila Tagore played a similar role as a woman caught inside of an imposed sainthood. Álvarez Mesén, whose previous shorts touched on uncomfortable taboos within family dynamics, but never quite as directly as here, has elevated her craft to something bolder and more confrontational. She has a new project already in the works titled The Wolf Will Tear Your Immaculate Hands, and despite any minor Clara Sola reservations, I, for one, am paying attention.

Writer: Igor Fishman

Mi Iubita, Mon Amour

A film of casually assured artistry and superficial topicality, Noémie Merlant’s feature debut Mi Iubita, Mon Amour is something of an archetypal French festival entry, albeit one that occasionally transcends its foundational triteness. Merlant, who also stars, balances the remarkable self-possession she maintained in Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire with other actorly indulgences that make the overarching bachelorette-party-abroad environment feel only fitfully lived in. In Romania for the pre-nuptials lost weekend, Merlant’s 27-year-old Jeanne and her three friends find their trip off to a rocky start when their car is pinched from a roadside gas station. Falling in with the family and friends of the 17-year-old Nino (Gimi-Nicole Covaci), the quartet’s touristic vacation plans evolve into something more hardscrabble. French complacency and inexcusable microaggressions are suddenly rubbing up against otherwise quotidian occurrences, like a lack of hot water, or more intensive-than-usual methods of fishing.

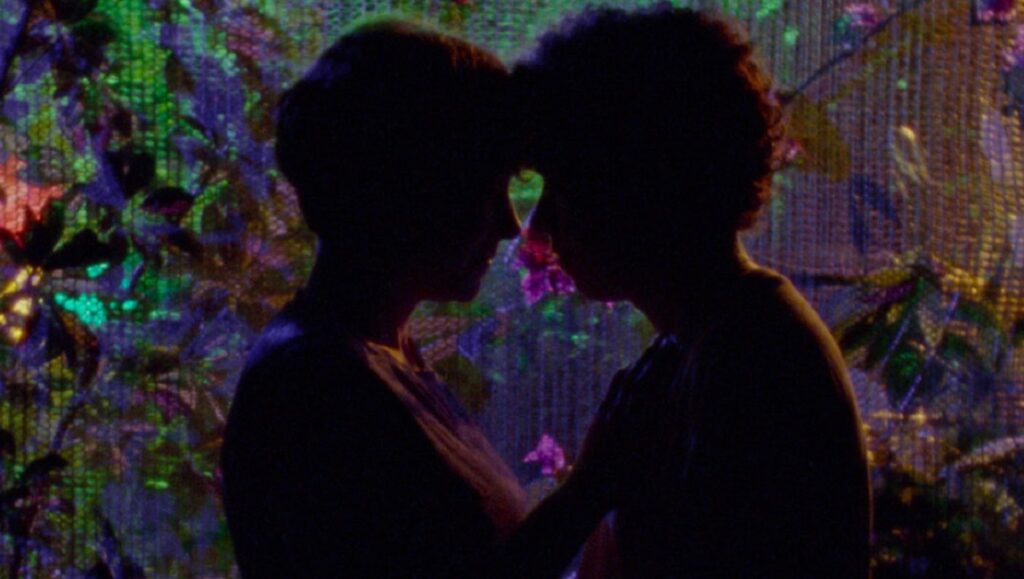

Romance blooms between the bride-to-be and her impromptu host, despite the 10 year age difference. The dalliance is given an inevitable timestamp, although that doesn’t dispel the sultry atmosphere, redolent with desire, and bolstered by the necessary intimacy of their newfound circumstances. Merlant favors the same sort of sensual tactility that’s so often linked to Sciamma or Claire Denis (although Mi Iubita, Mon Amour, if anything, recasts Valeska Grisebach’s Western as a romance), and more often than not, she makes good on yet another belabored trope of contemporary cinema, especially in a nightclub scene that’s remarkably earthbound despite the camera carving up the space to the sounds of David Guetta and Sia’s inescapable “Titanium.” When the film devolves into aphorisms, it’s difficult not to pine for some of the more wordless sequences that play with single light sources and emotionally symbolic reflections. Merlant herself bids adieu with tearful restraint à la Portrait of a Lady on Fire or Call Me By Your Name, in a move whose simultaneous appropriateness and lack of uniqueness sums up Mi Iubita as a whole.

Writer: Patrick Preziosi

Bruno Reidal, Confession of a Murderer

Director Vincent Le Port co-founded French production company Stank in 2013, through which he has managed to put out a handful of shorts including eerie, black-and-white gothic Le Gouffre (more of a short feature really, at 52 minutes), which won him the Prix Jean Vigo for short film in 2016. Le Gouffre didn’t manage to catch much attention outside the French festival circuit, ultimately becoming available to English speaking viewers via Stank’s Vimeo page, but its success in the director’s home country has led to the selection of his latest film for this year’s Cannes Critics’ Week lineup, his most internationally visible booking yet. The film in question — Bruno Reidal, Confession of a Murderer — is also noteworthy as Le Port’s first true feature-length project as a solo director, working from a screenplay of his own devisement, drawing from the memoirs of a real life killer.

Set in rural France in 1905, Bruno Reidal begins with the brutal murder implied in the title, a particularly vicious act of beheading committed against a 12-year-old boy. It’s a scene that Le Port opts to keep off-screen initially, one introduced to us free of context and edited so that we remain mostly in a close-up of the title character, left to interpret his facial expressions and signs of exertion. From this starting point, Bruno Reidal’s script works backward, establishing a framing device shortly after, the lead immediately turning himself in to authorities who have him recount his autobiography to a jury of doctors and psychologists. And so, the film quickly comes to be dominated by Reidal’s perspective, his florid philosophical voiceover (a good part of Le Port’s interest in his subject stemming from the quality of their prose) articulating a tumultuous emotional state and dictating the action of the forthcoming scene. A spare, direct film, this conceit accounts for Bruno Reidal’s most significant formal experimentation, undercutting and recharacterizing moments of violence by prefacing them with a defusing monologue. Le Port works this in gently, and thus, effectively, but his film wants for more ideas, the writer/director taken with the seemingly contradictory nature of this narrative and character, but disinclined to do more than note this disparity’s existence.

In the same tradition as René Allio’s 1976 cinematic adaptation of Michel Foucault’s I, Pierre Rivière, Having Slaughtered My Mother, My Sister, and My Brother…, this film wants the audience to perform their own interrogation of the title character’s actions — Are they the result of nature? Nurture? Abuse? Repression? — the hope being that we may begin to understand something unfathomable. Allio’s film (a high point of whatever this genre is) succeeded by making itself about what can’t be known, taking great pains to craft a recreation as close to historical fact as possible, while knowing full well that this itself is an act of obfuscation. Bruno Reidal considers similar concepts, but ultimately is most interested in positioning its title character as an emblem of humanity’s greatest struggle, the most extreme illustration of the tension between will and hedonism. While not an invalid angle, the direction from which Le Port comes at this narrative is the least intriguing, skipping by thornier material in favor of that which merely appears to be.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Zero Fucks Given

The mid-midlife crisis genre has always been a bit of a mixed bag, as most of the stories revolve around mopey twenty-somethings whose severe navel-gazing inspires fits of exaggerated eye rolls and loud sighs in even the most patient viewers. It’s tough to imagine an individual over the age of 30 who hasn’t muttered the words “Grow the fuck up” during a screening of something like Garden State or Elizabethtown, as they should. Zero Fucks Given isn’t necessarily immune to such exclamatories, but it does at least offer a novel spin on the standard proceedings, namely fixing its focus on how jobs can strip us of our humanity in ways both subtle and profound. Cassandre (Adèle Exarchopoulos) is a flight attendant for a budget airline who spends her days being berated by passengers and hawking glorified Amway products. When not working 16+ hour days, she seeks escape in binge drinking, recreational drug use, and random Tinder hook-ups. Directors Emmanuel Marre and Julie Lecoustre, making their feature-film debuts, highlight the soul-crushing mundanity of Cassandre’s life, with each day seemingly interchangeable from the next, a blur of airport tarmacs, mini bottles of vodka, whiny customers, and Instagram photo sessions. A job that requires zero attachments and an utter lack of emotion, it soon becomes clear that these very attributes have come to define every aspect of Cassandre’s existence, although cracks are beginning to show in the façade, whether it be a kind gesture to a passenger anxious over an upcoming medical procedure or Cassandre’s insistence on staying in the warm embrace of a one night stand for a few minutes longer. But once Cassandre moves back home for an extended stay after a work suspension, as such plots go, she is forced to confront ghosts from a past she has longed to escape, and the realization that her current predicament might be more than a bit self-inflicted.

There’s something both easily universal and poignant in the film’s portrait of the toxicity inherent within corporate employment, with the position of flight attendant proving an inspired choice, a dead-eyed servant whose forfeiture of an outside life is all but demanded. At one point, Cassandre participates in a training seminar in which she must smile for 30 seconds straight, chastised by management for showing the smallest signs of genuine human emotion. Later in the film, she takes part in a job interview that is the very definition of degradation, yet it’s all conducted in such a matter-of-fact manner that its abhorrence seems borderline innocuous, just another stepping stone toward both a promotion and a better life. It’s on the strength of these presentations that the film’s dead mother stuff feels especially grating. Sure, it affords motivation for why Cassandre would seek out such work, but it also robs the film of its thematic universality, which is certainly more important to the film’s success than any narrative or character-level veracity. For most people, career choices aren’t made on the heels of personal tragedy, and this plot filip does more to undermine the film’s messaging than it does to invigorate any deeper pathology (did I already mention Garden State)? It doesn’t help that Marre and Lecoustre offer nothing in the way of visual flair, which is partially by design, but it’s an approach that frustrates, especially in the film’s first hour; the movie hits the same note so many times it could be mistaken for an out-of-tune piano. As everyone knows, Exarchopoulos has presence to spare, a talented actress who deserves at least a lateral career to the one her Blue Is the Warmest Color co-star Lea Seydoux is currently enjoying; few working actresses are better as conveying so much in a single glance, her features rife with conflicting emotions and hidden facets. She alone makes Zero Fucks Given worth watching even as the surrounding film occasionally lets her down. Still, the sum is worth more than a couple of fucks, so credit where credit is due.

Writer: Steven Warner

Comments are closed.