The moving Parallel Mothers puts on full display Almodovar’s facility with wrangling the controlled chaos of narrative into a coherent whole.

If Pedro Almodóvar’s pandemic short The Human Voice hinted at a freshly energized director liberated from the burden of expectations, then his latest feature crystallizes this as fact. His first feature since the success of Pain & Glory finds Almodóvar in peak form, delivering a work of intertwining narrative and thematic complexity that echoes the sophisticated rhythms of All About My Mother, albeit with a tighter script tinged with political resonance. At first glance, Parallel Mothers may appear par for the course, after all, it sits so firmly in his dramatic wheelhouse, a melodrama centered on women, friendship, and motherhood, featuring some familiar faces (Rossy de Palma’s emergence drew joyous cheers at my screening). This go-around, however, the precision of craft combined with a confident sense of restraint gives the culminating drama a refreshing degree of weight and poignancy. Reinforcing this is an explicitly political thrust, one unusual for a director whose films so often confronted politics by irreverently broaching taboo. What makes this directness so effective is watching an idea set up in the first ten minutes quietly thread its way through the melodrama, only to resurface with full clarity, for a closing knockout punch.

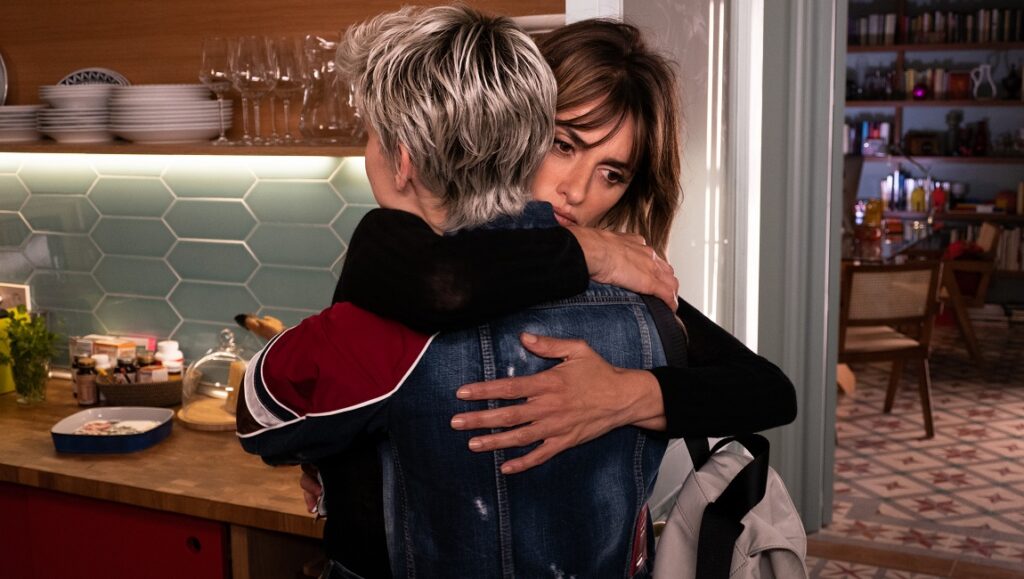

The center of the story is two mothers-to-be, Janis (Penélope Cruz) and Ana (Milena Smit), who bond in the maternity ward. The dynamics of this inter-generational relationship — Janis becomes a surrogate to Ana, whose mother is an absent and aloof actress — harken back to the friendship at the heart of All About My Mother wherein Cruz had once played the role of the young pregnant woman seeking comfort and support from Cecilia Roth. Twenty years later, Parallel Mothers reverses the dynamic, letting Cruz play the older more confident of the two, and in her own way pass the torch to relative newcomer Milena Smit. But while their relationship forms the meat of the story, the aforementioned bookends concern Janis’s quest to exhume the body of her great-grandfather (murdered in the Spanish Civil War), and gradually inform and empower with thematic thrust. Her cause mirrors a decades-long political struggle over the remains of the victims of the war buried in mass graves with over 110,000 still classed missing. The left-wing pushes for exhuming and identifying the buried as an act of healing, while the right-wing, reluctant to confront the past, urges against “reopening old wounds.” This tension is aptly paralleled within the two mothers: Janis takes pride in her familial roots, her apartment filled with photographs of her relations and history, while Ana resists confronting the trauma of her past encapsulated in the mystery of her baby’s father, yearning for a clean slate.

For Almodóvar, the past assails the present, and so he expertly cuts in between timeframes to grant us a richer understanding of Janis, whose elusive interiority Cruz captures with remarkable grace. Meanwhile, playful variants of his kaleidoscopic color schemes populate the frames, and everything from the wardrobes of the women down to their phone cases exist in delicate conversation as time flows backward and forward; the patterns of Ana’s favorite jacket reappear in Janis’s sweater dress after the two have moved in, and so forth. As the story develops, trailing down a series of twists and turns that test Janis’s resolve in her principles, the melodrama elevates into a rich portrait of pain, a mirror to the traumas of history that quietly lurk in the undercurrent. Almodóvar handles the shifting emotional terrain according to his trademark approach, affording sensitivity, empathy, and depth to his conflicted characters, ensuring that twists that may in less adept hands feel soapy or cheap carry the texture and gravity of realism. Of course, this measured control doesn’t preclude moments of pointed exuberance; a sex scene punctuated with Janis Joplin’s “Summertime” — her throaty croon swelling into the screech of a guitar solo — is a particularly inspired one.

What’s so impressive about Parallel Mothers, and Almodóvar’s oeuvre in general, is his capacity to wrangle the controlled chaos of his narratives into coherent wholes, even as they bristle against conventional structures. When we circle back to Janis’s mission to unearth her great-grandfather’s grave, the entire messy throughline compacts under the weight of a single culminating image. The stark return to the wounds of the Spanish Civil War is jarring and might catch some off guard, but it serves as a powerful rosetta stone for the preluding melodramas of the film. A story of two women grasping for and exhuming the pain of the past, while boldly pushing forward together. At the Q&A which followed the film’s NYFF premiere, Cruz revealed that Almodóvar approached her with a rough outline of the film during the press tour of All About My Mother over twenty years ago, and in fact, you can even find its title snaking its way into Broken Embraces as one of Harry Caine’s scripts. It’s quite something to consider how this story, itself a tether to the past, sat simmering on the back-burner for years until Almodóvar felt he could do it justice. The timing feels as ripe as ever, as earlier this spring, just as filming was getting underway, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez initiated plans to exhume and identify the bodies at rest in the Valley of the Fallen, a mass grave of more than 33,000 victims of the war. A moment which marks the beginning, not the end, of a process of reckoning with the past, a moment of both immeasurable pain and relief; Almodóvar seizes on it in the film’s startling final frame, as if to say: there in the open wound of the grave, our histories still throb.

Originally published as part of NYFF 2021 — Dispatch 5.

Comments are closed.