Spoon

Though we are emerging from Q1 2022 on shaky ground globally speaking, this recent past has already been canonized as a banner micro-era elsewhere in certain Internet music circles, with new albums from ascendant acts like Big Thief and Black Country, New Road (and a returning old guard contingent in Beach House and Animal Collective) embodying this supposedly exemplary moment in modern music. An overstated phenomenon dictated by rockist dogma notwithstanding, the current landscape makes for a curious moment in which to receive a new album from Spoon, a quintet of indie rock lifers whose initial come-up benefited from a similarly homogenous, indie-friendly critical perspective. Indeed, the band’s 2000s output boasts the highest Metacritic average of any other contemporary musician that decade – for those who care about such things – and their albums released in the 2010s, though embraced a little less warmly, each delivered their own distinct variation on a “for the fans” gesture. After a five-year gap between releases (the band’s longest to date), Spoon now return with their ninth album, Lucifer on the Sofa, which effectively sells the band’s turntables for guitars and offers up some of the most linear riffage of Spoon’s career. If a somewhat inelegant contraction for a group whose music already “rocked” in the absence of such direct assurances, the album slots tidily alongside Spoon’s usual assemblies of component parts slightly askew, sonically contiguous with the band’s oeuvre to date (if not exactly a broader, celebration-worthy musical moment).

Within that body of work, Lucifer’s taut aesthetic most immediately scans as an effortful pivot away from previous record Hot Thoughts, whose warped contours and unexpected orchestrations made it the first truly divisive release in a discography characterized by its consistency. Lucifer’s rock n’ roll retrenchment excels the most in its moments of ragged glory, as on album-opening Smog cover “Held,” whose tape hiss and studio chatter eventually builds to a full-band squall, its valorization of human contact in a world ablaze as potent in the song’s original iteration as Spoon’s here. The apocalyptic imagery recurs on Lucifer’s first single “The Hardest Cut,” though its motorized swing is less locomotive than lurching; a devoted ZZ Top homage so rigid that any potential for urgency is sapped dry. These louder earlier cuts are ultimately something of a feint, with the album proper hewing closer to its titular implication of a Death domesticated, borne out in a back half of muscular balladry and some of Spoon’s most direct love songs ever (the swaggering “Wild” and glistening “Astral Jacket” are highlights in this mold). While too gentle and seemingly sincere to offend, this stretch is also largely too bland to offend, featuring structures and sentiments whose uncomplicated ease corresponds to a lack of bite – not ideal in the context of this theoretically tough-as-nails rock music exercise, nor for a band whose advanced age render Lucifer’s mixed results a definitionally post-peak work. It’s hardly a total wash – Lucifer’s compelling title track and closer returns the group to their signature sense of agita and unease – but its modest appeal mostly affirms the idea that future Spoon successes will transpire on a smaller scale, matching neither the current indie music vanguard nor their acclaimed earlier era.

Writer: Mike Doub Section: Pop Rocks

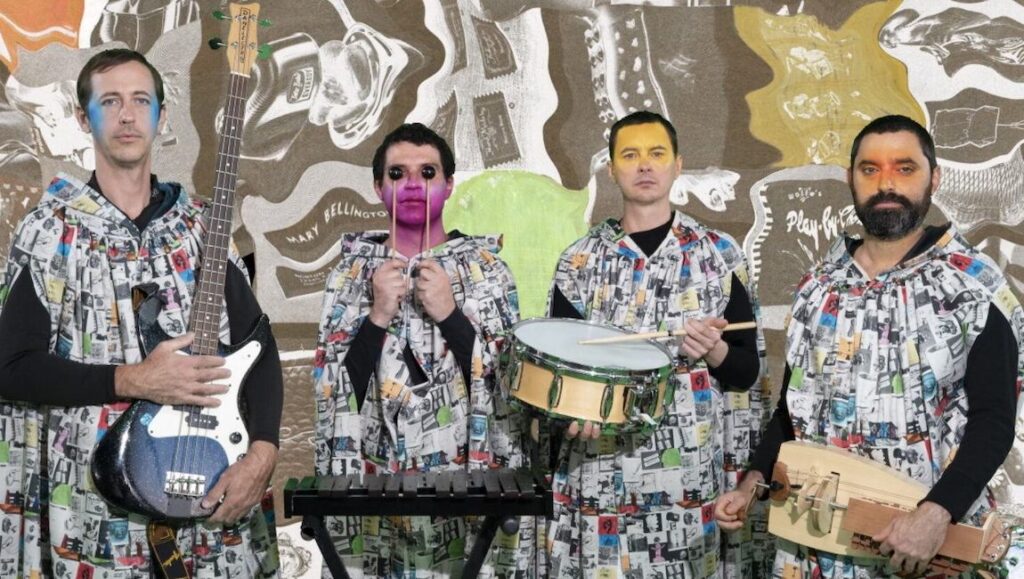

Animal Collective

Catching up with old acquaintances, no matter how close they once were, can be a daunting proposition. More often than not, these types of long-distance reunions can serve to confirm why initial dissociation occurred in the first place: that this individual standing right before you, previously a friend or confidant, has, for better or worse, irreversibly changed over time, where they’ll never again be the exact same person you grew apart from. They may even now hate this older version of themselves that you’ve clung to, perhaps seeing you as a reminder of the person they refused to be their entire lives. To bring this sentiment full circle, they also, more than likely, dislike the person you’ve become in the interim; and they have every right, as reciprocity is baked into such interpersonal dynamics. So these two former associates now see each other as complete strangers in this moment, mere passersby on the street; when you haven’t spoken to someone in a while, there’s a lot of realizations that can come rushing in when you once again do.

Keeping this in mind, the prospect of “chatting it up” with Animal Collective again after a turbulent decade of left-field experiments — this writer’s particularly fond of the supercharged, volatile melodies and hyperactive vocal trade-offs from 2016’s Painting With — and half-baked auditory concepts (another “visual album” that was as disposable as their last) about a record that’s supposedly a return to form isn’t a terribly enticing one. But fear not: Time Skiffs is the ideal type of reunion album, literally — it’s their first to feature all four members since 2012’s Centipede Hz — and figuratively, in that it doesn’t simply pay lip service to the past, but organically builds off of that musical foundation to create something fresh for the present. There’s a mellow maturity to the way the songs unravel themselves, patient while also, conversely, never calculated; spontaneity still plays a key role in their songwriting process, but there’s a lucidly defined framework for each track that felt lacking with their previous two studio releases. The amorphous beginning of “Prestor John” eventually entangles two separate musical ideas — and was originally conceived of as two entirely different songs — into one long, beautiful piece of aging, angular alt-rock; “Strung With Everything,” whose jam band-y approach would have felt right at home on Feels, continues the sentimentality, before reaching peak pathos as Avey Tare yelps out over the bridge: “Let’s say tonight you and me / We’ll watch the sky fall into pieces.” For AnCo, who’ve famously disregarded material wealth for the tranquility of familial life (“My Girls”), these little moments continue to matter the most.

But don’t get it twisted: they’re not reliving their glory days, because that implies their best years are behind them. As Avey beautifully puts it on the buoyant “We Go Back”, “I don’t feel the urge to turn back time / I just begin,” which is the closest thing to a thesis statement Time Skiffs produces. There’s always been a wide-eyed curiosity to how Animal Collective has seen the world, best encapsulated with the general optimism of “Cherokee,” which proposes that even some 20 years into our lives, we still have the capacity to “learn a lot” about our surroundings, our neighbors, and even about ourselves. So while the initial meet-up may present as a tad awkward, and you’d be right to be wary of such a proposition, Time Skiffs is a record that fully warrants the rapprochement, marking a rare occurrence where the reconciliation is just as exciting as the initial befriending.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: Ledger Line

Beach House

While any number of their contemporaries have stumbled and faded, or at the very least, committed themselves to performing exclusively for an increasingly niche, aging audience, Beach House miraculously remains widely popular and relatively cool. They achieve this in part by minimizing interactions with press and adamantly guarding their general privacy, having managed to obscure the nature of their lives outside the band for the 18 years in which they’ve been active. A simple yet effective tactic that has successfully protected their creative energy without rupturing their carefully cultivated persona, it has also maybe kept them from the things acts like Arcade Fire and St. Vincent thirsted after (arena shows, collabs with legacy bands), but Beach House’s cultural pervasiveness has yet to recede like theirs has, Victoria Legrand and Alex Scally’s music finding a whole new audience last year when Depression Cherry track “Space Song” became a TikTok fave. There even appears to be a collaboration with Ye in the works, suggesting that Legrand and Scally aren’t against working their tastemaker credentials, though, as they demonstrate on latest album Once Twice Melody, remain committed to their vision first and foremost.

It’s a vision that has mostly remained consistent from their self-titled debut, fleshed out with lusher and more expensive production as they went along naturally, but mostly holding fast, carefully refined, never wholly reinvented or subverted. Beach House’s previous album, 2018’s 7, strayed the furthest, recalibrating the band’s sonic stylings somewhat with assistance from producer Sonic Boom of Spacemen 3, but the more guitar-forward project remained firmly in proximity of Legrand and Scally’s larger aesthetic proclivities — vague, evocative, psychedelic lyricism; grand, ethereal, pitch-shifting vocals; big, dreamy soundscapes, etc. The uniformity between albums is such that critics of Beach House have an easy time issuing credible, reductive dismissals of their work, but Legrand and Scally have always been savvy about spacing out releases and avoiding oversaturation (the exception being the under-appreciated Thank Your Lucky Stars, which fell victim to being their second LP in one year), having instinctively kept pace with their listeners’ desire for new music.

In this way, Once Twice Melody may stir up conflicted feelings amongst Beach House devotees old and new (who made it the best selling album in the U.S. in its first week on sale) and further solidify the haters’ stance, the band having returned after four years away with a hefty double album of 18 songs that clocks in at a feature-length 84 minutes. Once Twice Melody is definitely a lot of Beach House, so much so that the album was doled out in 4-5 song chapters over the course of 4 months, a release strategy that didn’t cause a major stir, but does suggest a useful way of digesting this towering work. As suggested in press for Once Twice Melody, Beach House is well aware of the inevitable perception of this project as unwieldy, but feel justified in committing to this runtime in the spirit of iconically indulgent late works like Tusk and in defiance of a distracted audience increasingly disinterested in this release format. The resulting album is indeed a challenge initially, the stylistic variances between songs never dramatic enough to allow for passive differentiation from track to track, yet their melting together isn’t inherently a weakness. Beach House’s music most generally succeeds at fulfilling a dual purpose, their albums able to be appreciated as a whole piece (sometimes earning them a more pessimistic “background music” label) or as a collection of individual songs and singles.

Once Twice Melody proves no different, although many listeners may find themselves engaging less actively with this one, at least at first, but the duo’s knack for wistful pop melody remains incredible, and listeners will likely find hooks and bridges resurfacing in memories they hadn’t known they’d internalized. “New Romance,” the album’s second chapter, is perhaps most indicative of this quality, with “Runaway” and “ESP” being particular, early standouts reminiscent of Devotion era Beach House, but those who still appreciate the vibe will find that the edgier, sparer third chapter, “Masquerade,” and the more classically sweeping closing section, “Modern Love Stories,” have their own revelations to impart. Still, the stylistic variations between these chapters are not so loud, and some will understandably check out at points. What Once Twice Melody suggests is that, at this point, Beach House isn’t so concerned about chasing after those who are skeptical of tuning in, recent history suggesting that these two have maybe always been a little more ahead of the curve than we’ve assumed.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: Ledger Line

Mitski

Following a genuine attempt to quit music altogether, Mitski returns with Laurel Hell, another deeply personal record about her struggles with artistry and articulations of identity. Following an intense tour schedule for Be the Cowboy and a massive uptick in popularity due to some viral TikTok sounds, the stage was fairly well set to propel the performer to international stardom. And while that remains true, the complications presented on her latest album express an uncertainty regarding what she enjoys, an assertion of self in the face of fans that holds her dear.

The why of it all, then, is that Laurel Hell was a contractual obligation. At the end of 2019, Mitski claimed she was going to be leaving the music industry indefinitely. There was an immediate uproar amongst her massively online fandom, causing speculations about her health, the announcement’s potential as mere publicity for another album, or the validity of this truly being “the end.” In the midst of trying to quit, Mitski was reminded of the documents she had signed for her label indicating that she would complete another album. And so, here’s Laurel Hell, an achingly despondent album about the pains of artistic and personal freedom, of being an individual within the claustrophobia of the public eye. Lead single “Working for the Knife” is a pining for normalcy and for understanding an unclear path ahead. Where Mitski’s previous work grappled with her identity as an Asian-American, culminating in her statement that she doesn’t really align with that label, on this record the identity that she grapples with is that of artist, with the nature of that as a choice looming large through her lyrical explorations. Ruminations abound, but answers are in short supply — she doesn’t have it all figured out, and she doesn’t want people to think that she does either. Her lyrics are raw and bleak, finding little hope for the future, even in its uncertainty. And yet, the sound of her instrumentation retains the lighter tones that marked her previous work, adding a palpable, affecting dissonance and executed with clean precision, presenting a certainty that her lyrics lack.

Perhaps begrudgingly on the artist’s part, Laurel Hell nonetheless proves successful in landing its messaging. Despite the TikTokification of her fanbase, the blurring lines between artist and audience that this particular form of social media engenders, and the general attitudes and aims of artists who make it big on the platform, there remains a division between creator and consumer, something Mitski here grapples with in painful detail. But even after her attempt to jettison her musical career entirely, Mitski still committed to a tour and promotional cycle for Laurel Hell, refusing to sideline a record that stands as an expression of wounded self. Indeed, its very existence is proof of concept — art is hard, for any number of reasons professional or personal. While the future holds no such contractually-obligated compromises from Mitski and her musical outlook is murkier than ever, it’s in her willingness to confront these often unspoken, difficult truths as much as her wonderful craft that her legacy has been cemented.

Writer: Andrew Bosma Section: Ledger Line

Comments are closed.