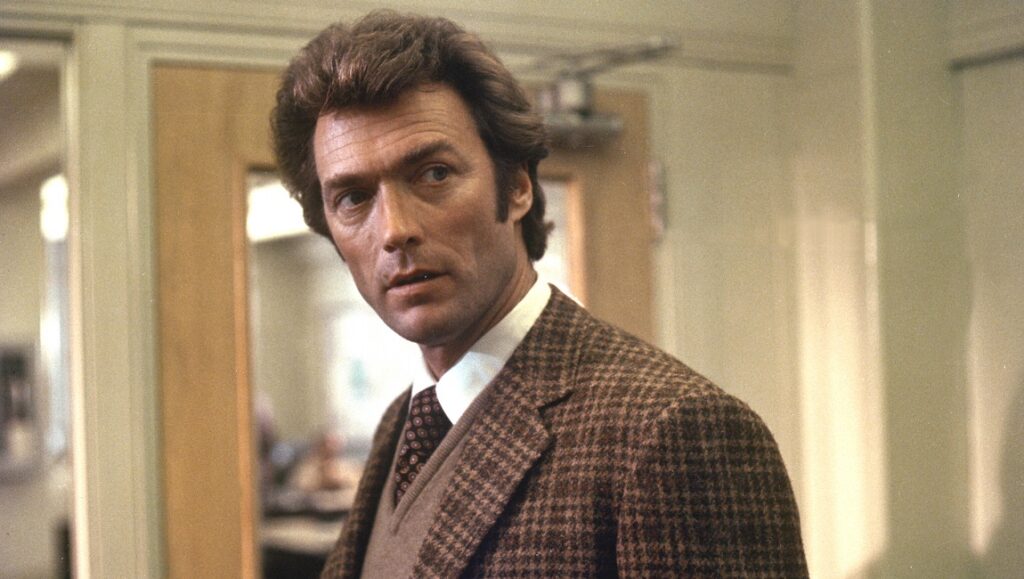

In 1963, John Wayne was just as much the face of the Western genre as he had been since 1939. The Duke’s charisma, one-size-fits-all philosophy of screen performance, and catalog of classic roles had made him an institution of the screen, the unimpeachable king of the West. Over the following few years, that foundation would be shaken to its core by the rise of Clint Eastwood, the face of the Spaghetti Western and subsequently New Hollywood action cinema, usurper of Wayne’s throne. The rivalry between the two is now infamous, notably centering around two Don Siegel films: The Shootist, Wayne’s final screen appearance and the set on which the two cowboys met for the first and only time, and Dirty Harry, a role declined by Wayne, who would spend the last few years of his dwindling career trying to mimic its success.

In addition to possibly marking the height of Eastwood’s popularity, Dirty Harry is often remembered as a gritty, hyper-violent crime series with loose, freewheeling new wave photography set to percussive jazz and moral messaging that borders on the fascistic: the police departments and the courts — paralyzed by empty commitment to social justice, due process, and the “rights” of unscrupulous criminals — are incapable of stemming the epidemic of crime and debauchery sweeping the streets, and Harry Callahan is the last sentry at the gate, the only man hard enough to do what needs to be done without collapsing into depravity himself. It’s also about aging. Callahan is a widower and a veteran officer who has become an institution of the San Francisco police force, increasingly running up against the growing progressivism of the criminal justice system and perpetually breaking in new, younger partners who “aren’t all that bad” as it turns out, before they get killed or otherwise spun out of his orbit. That dynamic is crystallized in The Rookie, a film that isn’t actually part of the series, though it may as well be. Per the title, it’s a Dirty Harry film from the perspective of the hapless sidekick who overcomes challenges in the field and his own demons to become a facsimile of his mentor. Eastwood’s protagonist isn’t quite the cop he used to be, slower and more sentimental with his obvious advancement in years, and the central relationship with Charlie Sheen’s rookie is celebrating the inculcation of values and sensibilities from one generation to the next… by 1990, Eastwood was already a deep traditionalist yearning for cultural continuities. The film is saturated with sleek nocturnal aesthetics, as though 20 years of shooting night patrol scenes had allowed Eastwood to hone in on a minimal, precise, unpolluted essence and then produce the entire film to that formula.

Eastwood’s approach to filmic form has been heavily informed by his collaborations with Don Siegel, who he has often cited as a mentor. Siegel is an interestingly situated figure in Hollywood history, today most remembered for contributing some of the most seminal titles to the New Hollywood overthrow of Golden age classicism, but Siegel came from the old studio system. And not as a director chafing at the creative limits of pragmatic convention in the way that Richard Brooks or Nicholas Ray had; Siegel was an old Hollywood man to his core, known for his economical filmmaking and dedication to breathing entertainment into time-honored genres. His ’60s and ’70s work isn’t as distinct from his ’40s and ’50s output as it might initially seem — aside from shifting with the times somewhat on tone and subject, his ethos largely remained intact, and indeed the flowing camera movements and dynamic approach to space are more suited towards his expediency and compositionally minimalist style. This is most borne out in The Shootist, consciously a final work for outspoken critic of New Hollywood John Wayne. Like clockwork, Siegel there snapped back into the rigid framing and theatrical dramaturgy of his ’40s work. Eastwood described Siegel as the fastest he’d ever seen at composing a scene and getting his take (preferably the first take), an approach that, having borrowed, Eastwood is now known for almost uniquely among contemporary mainstream filmmakers. This is deeper than mere efficiency, however; it’s a philosophy of intuitive realism that Eastwood brings to his art — as American critic Kenneth Turan put it to Eastwood at Cannes in 2012: “analysis leads to paralysis.”

Eastwood has turned this blueprint to his own devices, striking a unique emotional timbre in the balladry of his increasingly melodramatic late works. Perhaps the strongest example is Richard Jewell, a lacerating, morally forthright, near-Dickensian portrait of a simple, honest man slandered and vilified by dishonest people with institutional power. The titular performance from Paul Walter Hauser is of rare potency, and the filmmaking is dynamic form-follows-function stuff, blocking and editing to accentuate the affective narrative core. Despite dramatizing a real event from 1996, it’s the most present film Eastwood made perhaps this century, a clear and incisive allegory for many of the heated issues swirling in the ether of public discourse these last few years: the relationship of the police to the people, class dynamics, mob justice, mistrust in the media — each handled with resounding moral clarity. Late Eastwood’s pivotal relationship to history is here at its most multivalent.

On June 18, 1971, Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs. As Watergate co-conspirator and Nixon confidant John Ehrlichman would later explain, this was in effect an attempt to criminalize the enemies of the regime — the counter-cultural movement and Black populations. Six months later, Dirty Harry was released, an almost perfect coagulation of the maladies Nixon had diagnosed America with. The serial killing antagonist is a long-haired youth with a peace symbol on his belt buckle, while Black people are presented as either criminals or victims. This aesthetic has emotional currency in American politics even today. In January 1973, in the midst of the Watergate scandal, current American president Joe Biden began his long tenure in the US Senate. His legislative career is often characterized as being “tough on crime,” a posture downstream of the cultural milieu Dirty Harry emerged out of and helped to perpetuate.

By the late-’80s Clint Eastwood was already old for a leading star of the time (he was born just one year after Audrey Hepburn) and themes of aging and respect for the elderly began — and have continued — to come thick and fast as he maintained his position at the heights of Hollywood. Most widely cited in this regard is probably Unforgiven, a critical triumph for Eastwood, but it’s material in all the films he stars in, and the specter of it lingers over half of the rest. Even the films ostensibly about youth — Flags of Our Fathers, Letters From Iwo Jima, and Jersey Boys are not just narrative portals into the world of youths who are presently old, but emotional portals into their lives as well, inviting viewers to understand and respect a rapidly disappearing cohort who were young adults in the ’40s, ’50s, and early-’60s through a vision of their shared cultural memories. Perhaps Eastwood’s most explicit exploration of age, then, is Space Cowboys, an archetypal “old fogeys proving they’ve still got it in ’em” affair, following former Air Force pilots aggrieved that they got frozen out of the space race half a century prior by the founding of NASA. Clint gets the gang back together, heals some old wounds, and they all prove they can do anything a young hotshot astronaut can. It’s particularly fascinating to watch Space Cowboys in 2022, at a time when retirement is often foregone until deep into old age, societal institutions are clogged with people who won’t retire (even critical aspects of American governance now routinely feature seniors hanging around until the very moment of death), and the profound threat of demographic aging looms on the not so distant horizon. Indeed, America is increasingly sliding into gerontocracy, and what better example of that than Clint Eastwood himself, having directed what might not actually be but certainly feels like more Hollywood major studio features in the last decade than directors under the age of 30 cumulatively.

It’s fitting, then, that Cry Macho — the first film Eastwood has directed since the election of the oldest president yet, a man frequently accused of suffering severe cognitive decline — would border on self-parody. Clint is yet again playing a tough hombre, a lanky, slow-moving nonagenarian ranch hand recruited to track down a missing boy in Mexico. Putting aside the astonishing and somewhat bizarre feat of a 91-year-old directing and playing the lead in a neo-Western feature film, Cry Macho is in many respects completely indistinct from a random direct-to-streaming feature that will forever sit in its small corner of the Internet, slowly accumulating watches — and that’s what a screen adaptation of the novel would have been perceived as, were it not for Eastwood’s involvement. Many of his trademarks are still present: the thematic content is yet another refinement of the preoccupations Eastwood has been whittling for 50 years. More surprising, though, is how strong the aesthetic continuity feels. Frequent Marvel cinematographer Ben Davis’ dry, motive, handheld digital photography makes Cry Macho into a truly imagistic experience, with as firm and deep roots in its aesthetic forebears as the text has in its thematic forebears. Here is the last outpost of a cinematic methodology as old as Eastwood himself; transfigured from a film language devised to sell B-movies to small community theatres in the early days of sound to a post-Oscars, post-Cahiers du Cinéma film that celebrates the value of those same small communities and the families that constitute them. If you have any love for Eastwood, you’ll enjoy this.

The 20th century is a mythological time in our imaginations, from the decline and collapse of 19th-century empires to the fall of the Soviet Union, filled with events and figures that constitute boulders in the historical landscape around which the baseline ideology of society is formed. The Watergate scandal feels equidistant to the present as it was to many of a generation who first heard about it in the early aughts. As has been discussed in far too many places, the 1960s turned culture on its head. But we have just lived through a far bigger upending. In the past, major media organizations had a very palpable oligopoly over the rationalization of history, and consequently our collective myths. A class of journalists earnestly sought to fashion a linear, comprehensible analysis of a world operating through the erratic movement of billions of individually unpredictable nodes, and depending on your desired outcome, they did a good job. But with the rise of the 24-hour news cycle, the Internet, social media, the democratization of culture, and the marketization of celebrity, we have pierced that veil. The confusion, the alienation, the perpetual chaos of how you relate to culture today is an expression of this. You are reading this on an outlet that on every level would not have existed without all the above. This is also in part why Hollywood can’t make any stars with the cultural currency of Leonardo DiCaprio or Natalie Portman anymore, and in a sense nobody can. Our collective attentions and our imaginations have been fractured, as have the media sources we consume and our cultural references. Against all this, what Eastwood represents today is clear. He is one of those immovable boulders from the hallowed halls of the 20th century, still with us and still maintaining the same frenetic pace he was decades ago. The man who succeeded John Wayne more than 50 years ago has, on the basis of that irreproducible cultural status, the ability to make whatever idiosyncratic film he sees fit. It may not all be in contention for the peak of film artistry, and perhaps often isn’t even that good, but if Clint can continue to burrow down his own tangent in defiance of the march of culture in the other direction, he deserves another 92 years to do so.

Comments are closed.