One of the most enjoyable films presented in this year’s Crossroads Festival is also one of the shortest. In Object Permanence, Alix Blevins offers the viewer a series of five shots in just over one minute. In the center of each shot is an object — a watch, a blanket, a copy of the collected writings of Hollis Frampton, etc. And Blevins uses the oldest trick in the book, an in-camera edit, to make those objects “disappear.” While the film harks back to cinema’s infancy, in particular the films of Georges Méliès, the title undermines our sense of awe. Blevins refers to the psychological principle by which we know that things continue to exist even when we can’t see them. Object Permanence is both a demonstration of the magic only cinema can provide, and our full awareness that it’s all just a trick.

Each year, curator Steve Polta assembles a weekend-long program of experimental films from around the world, and Crossroads has long been known and admired for its diversity, not just in demographic terms but also in terms of aesthetic orientation. While this year is not an exception, I did notice that there are more common threads and intersecting approaches in the program than I’ve seen in years past. Such perceptions are inevitably personal, and are just as likely to occur to a given viewer as not.

But Crossroads does seem to feature a large number of works that suggest a broad movement back to some of experimental film’s most basic elements. Landscape films are back with a vengeance, and while they never really went away, a large number of artists seem to be engaging with subject matter that is more elemental than conventionally temporal. And often this non-humanist subject matter provides a framework for filmmakers to explore the medium-specificity of analog production, working with, and on, the materiality of the filmstrip. Hand processing, “third eye” image toggling, bipacking, optical printing, scratches and sprocket holes, and painterly abstraction dominated the festival this year, and there may be some very good reasons for this.

It’s often difficult for artists to address cultural and political sea changes while they are in progress. As we know from the Covid-19 pandemic, attempts to document vast changes in the way we live can lead to unexpected insight, but it can just as often produce work that privileges the lone individual’s affective responses to big phenomena, and at times this leads to solipsism and injudicious tone. Today we are in the midst of other sweeping changes, having to do with the future of cinema, along with everything else. As digital streaming dominates our mediascape, it makes sense that film artists would concentrate on film-as-film, perhaps treating the medium’s obsolescence as a chance to historicize “cinema” as a set of options and procedures. But there is also the worldwide movement toward fascism to consider, and like Covid, it’s very possible that artists feel somewhat cowed by these developments, not yet capable of making strong statements about them. This in turn may be resulting in a temporary retrenchment, with cinema circling back on itself, because it is an ontology that feels manageable and bounded.

In this respect, it’s noteworthy that Crossroads’ centerpiece screening this year was Expedition Content, a feature-length experimental documentary by Ernst Karel and Veronika Kusumaryati of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab. The film is based on audio recordings made in 1961 by Harvard ethnographer Robert Gardner during a trip to New Guinea, and as we listen in we can hear educated scholars engaging in smug (if amusing) colonialist assumptions about the Hubula community they’re there to study. Expedition Context is nearly imageless, allowing the viewer to simply listen in the dark to these audio records. In this way, Karel and Kusumaryati accomplish two intertwined objectives: the film critiques the ethnocentric flaws at the heart of the Harvard project, of which its makers are a part, and it also withholds film’s imaging ability, in order to consider film’s own role in the colonial project.

As is always the case, Crossroads featured works by major filmmakers that are playing in San Francisco for the first time. Some of these are well-traveled by now, speaking to the consensus that has formed around their high quality. These include Ross Meckfessel’s complex Estuary, Michael Robinson’s emotionally resonant Polycephaly in D, James Edmonds’ lush, painterly Configurations, and Dani and Sheilah ReStack’s performance-based Future From Inside.

In other cases, Polta selected newer films by major contemporary makers whose work expanded on their overall practice in satisfying ways. Jodie Mack’s M*U*S*H continues her mid-career interest in foliage, using Rose Lowder-like frame alternation to display a multitude of random scatterings of grass and flower petals, which at times seem to assume the look of anaglyph 3D. Kevin Jerome Everson’s Patent 1,571,148 observes a man in a garage working on the engine of his Pontiac, but the film (either due to Everson’s camera movement or an internal sprocket problem) introduces a lateral judder that points obliquely back to the film apparatus itself.

Dreams Under Confinement, the latest film from Christopher Harris, uses Google Earth and police radio transmissions to indict the use of big data to target vulnerable populations. Pigment-Dispersion Syndrome by Jennifer Todd Reeves expands on her interest in agitated painting surface applied to found footage, in this case a series of eye exams and images of women working in the laboratory. And one of the best films on the docket, III by Alexandre Larose, finds the filmmaker again working in his dense, time-intensive mode of superimposition, this time applied to a work of ghostly portraiture.

And two long-reigning champions of avant-garde filmmaking appeared in the program with films that not only extended but also expanded their ongoing aesthetic projects. To my mind, giving two or three minutes to the work of Friedl vom Gröller is always time well spent. She was represented by three recent films, the best of which, la mia Camera, is a nearly-perfect study of striped curtains and tent flaps rippling in the wind. (Where other contemporary filmmakers struggle to jam too many ideas into a single film, vom Gröller wisely gives her individual gestures the breathing room of a single short film.) And perhaps most poignant of all was High Heel Beloved, the capstone film in Leslie Thornton’s decades-long magnum opus Peggy and Fred in Hell. In this film, Thornton’s two curious child performers find different pairs of abandoned shoes and try them on, an utterly innocent moment of gender play. The film is dedicated to the memory of Donald Reading, aka “Fred,” who sadly passed away in 2020 at the age of 42.

But the main excitement from Crossroads always comes from discovering work from filmmakers with whom I was previously unfamiliar. This year, these were the entries that operated within the basic parameters of experimental film, but applied those techniques in bold new ways. Zack Parrinella’s Color Prism Suite #2: Withering Ends is a film that displays affinities with the classic mode of structural film (especially Frampton and John Smith), but injects it with his own unique sense of humor. Isolated shots of objects in the world are edited into groups, usually based on color, sometimes based on shape, and eventually according to rules that only Parrinella knows for sure. It’s also one of the few works in the program to engage in sound design in a conceptually rigorous manner. The Girl Who Is, by Milwaukee’s Sara Sowell, is a deconstruction of television footage (in this case, Tyra Banks and America’s Next Top Model) that recalls certain works by Kurt Kren, or even Christopher Harris’ Reckless Eyeballing. But she reassembles the images and sounds into disconcerting shards, taking a relatively commonplace idea (the beauty standard and its effects on women) and making it palpably felt.

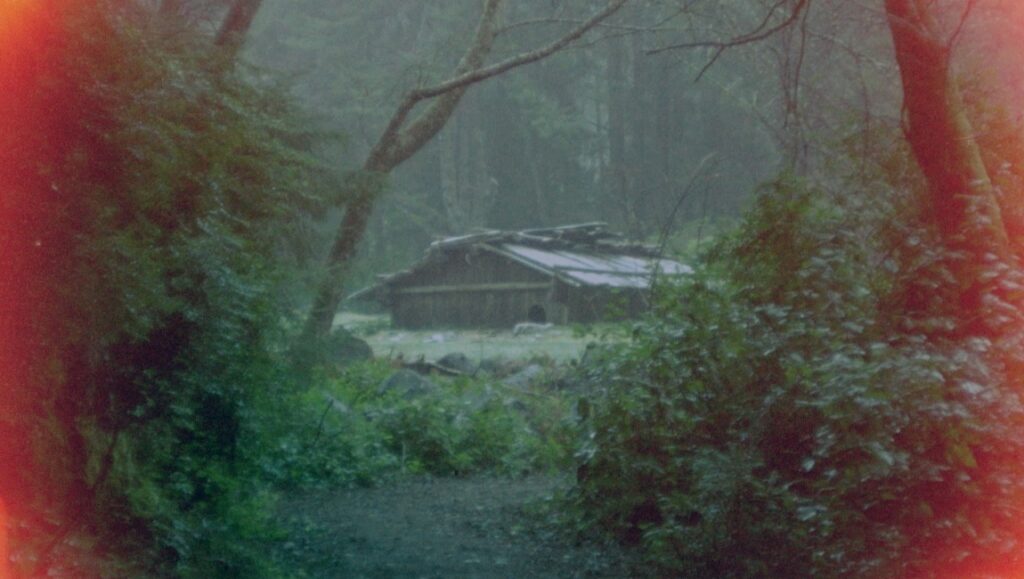

Another filmmaker working in that neo-structural vein is Emily Chao, whose strong yet delicate work Crossroads has featured in the past. With her new film Light Signal, Chao emerges as one of the only younger filmmakers to display the influence of David Gatten, while taking that influence in a whole new direction. Light Signal is a landscape and seascape film, poised on the edge of a shore with a prominent lighthouse. She intercuts this footage with purely optical phenomena, alternations of black and white that adhere to explicit duration rules. White phrases emerge from the inky screen: “went to pieces,” “earth opened in cracks,” etc. Chao gradually moves us inland, to a rustic shack in the woods, and eventually back out to see and onto the island of Alcatraz. As much an homage to the lushness of celluloid as an elegy for the way it helps us see, Light Signal is one of the year’s standouts.

But not everyone was looking backwards. At least one film in the festival provided a glimpse of the future, which is ironic considering it dates from 2020, one of the oldest works screened. In Marcos Serafim’s Autoimmune, we observe for nearly fifteen minutes while an AI computer program scans, manipulates, and reassembles sounds and images from the 1980s, material centered around the AIDS crisis. It’s still a bit presumptuous to speak of the “end of AIDS,” considering the economic and geographic disparities in terms of treatment availability. Still, the existence of PrEP represents a sea change in the impact of the one-time epidemic, such that the disease can now be examined historically. How did governments respond? How did the media foment fear and encourage prejudice? And how did artists and activists speak back?

Autoimmune uses the projection frame as a desktop image, and for most of its running time we are watching a self-guided program go through its paces. We see fragments of media material that will be instantly familiar to anyone who lived through the period: Rock Hudson, Magic Johnson, Ronald Reagan, and the infamous British AIDS PSA that depicted potential victims of the virus as bowling pins mowed down by the Grim Reaper.

Serafim displays these images as a kind of mutating gridwork, with various faces and environments combined to suggest an impersonal data-mosh of AIDS as a media-defined pandemic. Reagan’s face is grafted onto a gay porn model; famous faces are blended into a blurry, composite human visage; and TV sounds are collapsed into a dark drone that resembles the stochastic compositions of Ligeti and Xenakis. The one relative constant in Autoimmune is poet Essex Hemphill, whose words and face resist complete digitization. If human history is to be organized and preserved by algorithms, Serafim suggests that some people made indelible impressions that can never be calculated away.

Comments are closed.