Because of the sheer breadth of work on display — 10 programs, with an average of seven or eight films per program — the annual Crossroads festival in San Francisco offers a fairly reliable core sample of the current state of experimental cinema. Artistic director Steve Polta’s selection for Crossroads has always covered a wide array of styles and approaches, which makes the point that much more striking. A few common elements assert themselves again and again in the 75 works in this year’s festival. Above all, one can see a desire to move away from the clean, endlessly malleable sounds and images of the digital era, and a resurgence of old-fashioned photographic chemistry. For quite some time we’ve seen filmmakers shooting and processing in celluloid, and then editing and projecting the final work with digital media. But more and more, one sees a tendency to use film the way earlier generations used painting following the advent of photography. A newer medium has cornered the market on verisimilitude, and this frees the older medium for experimentation on the fringes, characterized by the forceful assertion of film’s physicality.

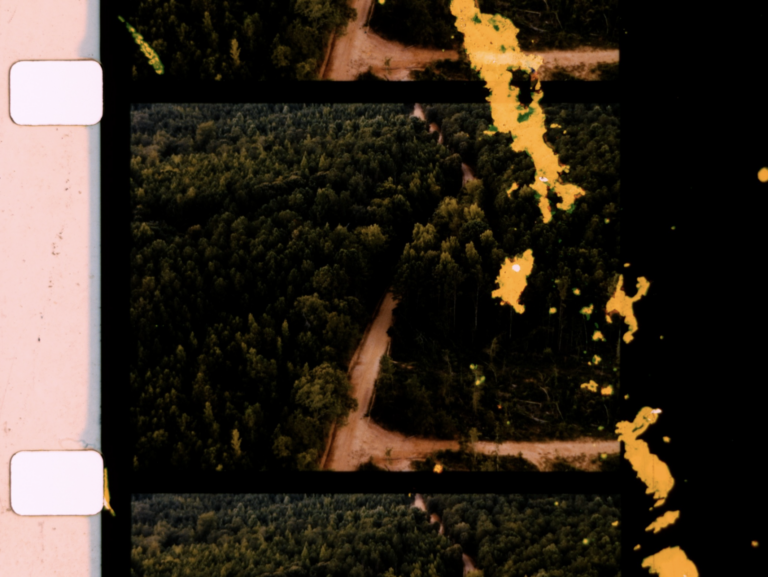

This year’s selection features more purely silent films than in previous years, marking a return to the primacy of visual input that remains most closely associated with Stan Brakhage. But there’s also a lot of aggressive tactility within the image: scratches, developer spots and fixer blotches, the horizontal ghosting of film slipping off the sprockets and vibrating in the gate, painting and tinting, film subjected to natural processes like molding and decay, or filmstrips dragged, buried, baked, hydrated, crumpled, or stripped. There is also a significant presence of Super-8 filmmaking, a medium that is not quite as amenable to physical manipulation as 16mm but whose bright colors and prominent grain often serve to induce a historical aura, an aesthetic adjunct to the late Mark Fisher’s concept of hauntology.

In some instances, artists are indeed looking backward, indulging in nostalgia for a very different image culture, one implicitly defined by photographic chemistry as, if not a guarantor of, at least a tether to the real world. Digital film technology, like any new development, initially offered a seemingly limitless horizon of possibility, giving artists the capability to generate any image or sound they could imagine. But as with analog video, the Internet, and of course artificial intelligence tools, those possibilities are quickly curtailed, if not completely foreclosed, by the demands of capital. So film, being an industrially obsolete object, may offer both a safe haven from the profit motive and a place of cultural retreat. Borrowing Raymond Williams’ formulation, we can see cinema’s role as both residual and emergent, depending on a given artist’s orientation and concerns.

There are around a dozen films that explore natural forms, in particular the interface between landscape and the photographic apparatus. The Land at Night, by the veteran Australian duo of Dianna Barrie and Richard Tuohy, is arguably the strongest example of this approach. It’s certainly the most maximalist, its 14-minute runtime seeming positively luxurious in this context. As it says on the tin, The Land at Night alternates between environmental forms as barely visible onscreen and their harsh illumination, organized in a flicker pattern that is accentuated by the pair’s jagged, Cubist editing. The woods, the beach, and other outdoor locations articulate themselves onscreen in a pulsing, multi-perspectival rhythm, as the high aperture cinematography heightens the presence of film grain. Like a number of films, The Land at Night is primarily a visual experience, its soundtrack seemingly an afterthought. Images of ocean waves are accompanied by recorded waves; the beams of a house under construction are matched with the sound of hammering; etc.

Above all, what The Land at Night accomplishes is an assertion of the specific properties of cinematic light under intensive montage conditions. Unlike digital, which shapes and reshapes its image with pixel movement, the film frame is whole unto itself, impressing itself on the retina as a jolt of energy. So when that image collides with another (in this case, images that are similar in subject but different in orientation), the eye is coaxed into forming a relationship among differences. This is not a new analysis, of course. It goes back at least as far as the writings of Eisenstein. But where the Soviets were engaging with cinema as an alternative to live theater, we confront cinema as an alternative to various digital tools that have largely surpassed the persistence of vision and are poised to surpass human intention altogether.

With this in mind, the application of analog cinema to matters of landscape and waterscape is quite logical. Cinema, despite its plastic base, is the result of inorganic chemical processes that seem more “natural” than technologies that derive from computer data. A late-19th century industrial process becomes the new nature precisely because of the qualities of the thing that is replacing it. The chemicals face outward, producing a record of tangible atmospheric events. Some iterations of this “green materialism” are more complex than others. Spanish artist Laura Moreno Bueno’s series of three ULÍA films are among the most compelling landscape works in Crossroads, partly because she focuses on a few specific formal elements (most notably, the vertical judder of sprocket misregistration) to desolidify her pictures, conveying the palpable ambiance of her chosen locations. In a very different vein, the three Sunprints films by Canada’s Barbara Sternberg employ environmental footage as the ground for dense, skittering visual collage, incorporating flashes of portraiture, human movement, and fragments of narrative action. In her use of muted color and especially her sturdy, intuitive editing, Sternberg displays affinities with other major Canadian filmmakers, including Joyce Wieland, Ellie Epp, and especially Jack Chambers.

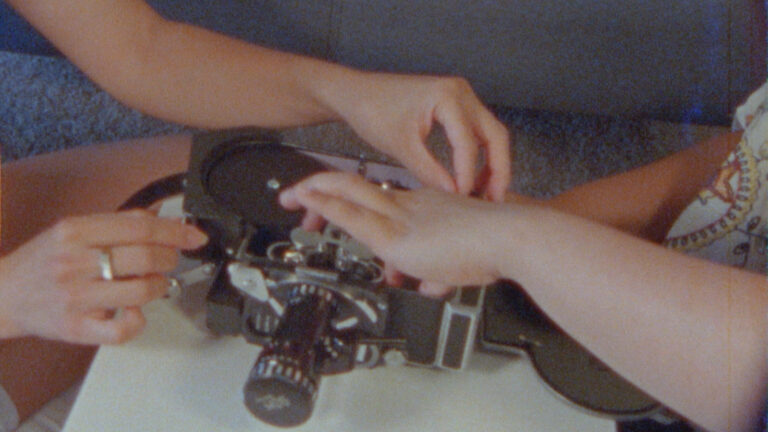

An even more complex meditation on the cultural role of film technology can be found in Our Cave by South Korean filmmaker Heehyun Choi. Expanding on her earlier film This Isn’t What It Appears (2022), Our Cave again incorporates archived photographic images taken by American servicemen stationed in Korea in the 1950s. Where the previous film subjects those images to scrutiny and duplication, working to reveal their unconscious traces of Orientalism and colonialism, Our Cave extends these questions to the entire cinematic apparatus. Throughout the film, we see Choi replacing the camera with other objects (an apple, for example), replacing other objects with the movie camera (a vanity mirror), and eventually substituting lengths of film for other ordinary objects (water for plants, soup in a bowl). Alluding to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (itself a touchstone for apparatus-based film theory in the 1970s), Choi reverses and undoes the connection between the filmed object and its celluloid double. Even though cinema may maintain more of a physical connection with its object than its digital counterpart, Choi warns against lapsing into traditional models of fetishism, reminding us of their imbrication with systems of power and control.

These technologies of vision are also examined in two films that, despite their apparent differences, both engage with issues of materiality, performance, and surveillance. Ayanna Dozier’s Bounded Intimacy appears as if it is a film randomly shot with a Super-8 camera out a downtown window. But through a series of rigorous zooms and reframings, we see a woman (Gabriella Garcia) on the street performing as a sex worker. Her revealing outfit marks her as other amidst the various activities on the street, as she offers herself as a historical spectacle, both the outfit and the film material creating a general vibe of “Downtown NYC in the late 70s.” In her more overtly materialist project Boundary Exercise (On Perambulation), Elizabeth Webb takes a filmstrip and drags it through the dirt, burying parts of it, in order to record this physical action on the surface of the film. However, we also see footage of Webb performing these rituals, and we discover that the film has been positioned along very specific boundaries. Webb marks the property lines of a plantation her family owned, using film as both a surveying tool and a line of restriction. Both Dozier and Webb use film as part of broader performance practices, their bodies soliciting the gaze in order to shift our attention to the history inscribed in public and private space.

Meanwhile, two other films in this year’s Crossroads draw their own line in the sand, considering the dangers posed by both 20th-century people-movers and 21st-century thinking machines. Hampaat (teeth), by Finnish filmmaker Ville Koskinen, begins with an image that went viral not too long ago, of an escalator breaking apart mid-use, with one person falling into the works and being ground to death. Following from this, Koskinen uses close-ups, superimpositions, and linear precision to create a potent piece of avant-horror. The never-ending geometry of the escalator, its thin metal lines moving slowly across the screen, calls to mind the purely graphic films of the early 20th century but with an undercurrent of menace. In a very different manner, Canadian stalwart Mike Hoolboom considers the future of data technologies in Wind, a short confessional poem presented from the point of view of an AI reflecting on its existence. The image track is composed of found images of human beings being buffeted by strong gusts of wind, and near the end of the film, the AI voice tells us that it selected and arranged the shots. “A wind is coming,” the voice warns. If there is one recurring idea to be found in the films of Crossroads 2024, it is that artists, and society more broadly, must decide which way we will go. Because that wind is already here.

Comments are closed.