Story of a Mouse is unsurprisingly beholden to a certain vein of hagiography, but it’s also compellingly as racked with contradictions as its titular subject.

Some of the first images we see in the new Disney+ documentary Mickey: The Story of a Mouse are of children running toward the titular costumed character, their faces bursting with excitement and joy. Upon reflection, it’s hard not to wonder where such reverence arises from. In fact, I have similar memories from childhood, despite the only Mickey Mouse film I had seen being Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983) on VHS, which in this documentary’s own words is more of a Scrooge McDuck cartoon. Mickey has only become less prominent since then, so it’s not unreasonable to think that these children born in the late 2010s have never even seen him in anything. The Mouse’s place in culture is indeed bizarre, and the contradictions rest on the surface: he’s “frozen in amber,” no longer a character, or even really an idea. It’s rather as if he’s been an iconic and much-loved character for so long that the recognition continues on momentum alone. But such contradictions don’t exist in the eyes of these children, and Jeff Malmberg’s film could easily cruise on this notion alone — but it doesn’t. Instead, Story of a Mouse tries to paint a broader picture, even despite its obvious Disney+ hagiography; the dance between what’s kept on screen and hidden off becomes a complex and compelling throughline.

One of Walt Disney’s catchphrases claimed “it was all started by a mouse,” but it was he who gave his voice to Mickey, and in some sense, they are one and the same, entirely inseparable. The film makes a point to draw parallel between a mouse and a man who started from the bottom; Mickey was even born from a low point: after Walt had his character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit taken from him, the film does acknowledge that this origin story of Mickey — conceived on the train ride home after losing it all — was re-told in many different ways. But even if the film argues that the story is more important than truth, it does regard it as “pure myth-making, ” and seems compelled to argue this point rather than taking it as a given, which makes the strange twists and logic of this mythology more obvious. Considering the domesticity of the ’50s Mickey shorts with the place Walt was in his life, for example, is odd when animated shorts as a medium were winding down at the time, made with decreasing budgets and resources.

Still, the idea of Walt losing touch with Mickey as his voice became increasingly incapable of producing that iconic falsetto is quite a brilliant thread to follow. It helps articulate the way that Mickey was growing into an icon outside of Walt, and continued to do so after he died of lung cancer in 1966. Much of his mythology is reproduced, if in a more complex way, but the film doesn’t suggest that Walt’s death brought on Mickey’s decline; rather, Malmberg posits that in some ways it gifted the character a new birth, fragmenting Mickey into both symbol of the brand and a reflection of the culture around him, extending even to the counter-culture. The story of hippies protesting in Disneyland, chanting for the liberation of Minnie Mouse, is detailed sympathetically; the film even concurs when it later shows her mistreatment in the early shorts. But though this reflects a cultural divide that has long settled into history, the idea of Mickey representing us could, at one’s most cynical, be seen as a way to make excuses for the company. For instance, when the film states that the racism of some of the Mickey shorts sprung from a broader racist culture, it’s both true and not: they were created within a specific context, of course, but also by specific people, with whom responsibility must fall.

Those protests are placed in conversation with the company’s famous litigiousness, though this thread is executed with an excess of sympathy that feels more like PR than anything else in the film, as if it was all just an unfortunate necessity. But the idea that Mickey’s reclamation could only go so far is acknowledged as (part of) what turned him into a “hollow” corporate logo in the ’80s, when he wasn’t allowed to represent anything more than the company that owned him. We see a balloon inside of a balloon he’s overly protected, closed off from the world. A collector at one point argues that Mickey’s power is in abstraction; if he’s allowed to become a pure icon — simply three circles — he can then mean something to everyone, a point underlined quite creakily by a diverse group of interviewees against candy-colored backgrounds. But this also risks Mickey being hollowed out in the opposite way. For anyone to be able project onto him, for the character to become pure abstraction, he must become an absence, a sort of void that can’t hold any particular meaning too tightly.

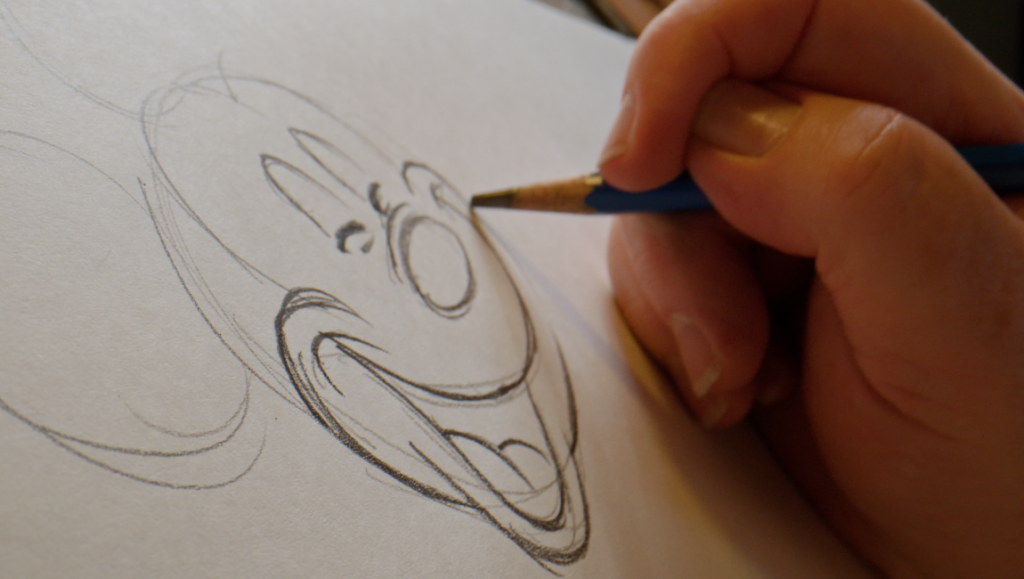

In one of the documentary’s many different threads we follow long-time Disney animator Eric Goldberg. He’s incredibly charming and a profound fan of Mickey, here making a great case for some of the ’40s shorts that this writer had always dismissed, quite clearly demonstrating their influence on his work as the animator of the Genie in Aladdin (1992). He’s also creating a new short with a scrappy team of three, in contrast to the hundreds he speculates once worked on Mickey cartoons, and it’s framed as part of a broader revival of the character along with a new series that has given Mickey a fresh design and the ability to be wacky again. But shorts have a very different meaning and function now, and Goldberg’s Mickey in a Minute (2022) is just a collection of references to the only ones that really matter: the theatrical ones. Mickey ends up where he’s doomed to always be, trapped behind the wheel of the Steamboat Willie; he’s even sucked into it. Yes, other people have voiced Mickey after Walt, but they all say they’re doing it in service to his version; they all willingly live in his shadow.

But if we are to accept the thesis of Mickey: The Story of a Mouse, that America and Mickey changed together, then what does it mean that Mickey stopped changing? It’s a powerful statement of the decaying American empire — omnipresent and expanding, but always gazing nostalgically backward — which is left just off screen. Indeed, the film comes at Mickey from so many different angles: It’s partly hagiography of Walt with tasteful recreations, partly a making-of for the Mickey in a Minute short, and partly something akin to Kids React, assembling responses from a selected general public. This isn’t just because he’s an icon big enough to encompass all of this, but because there is a complex interplay between what the film wants to say, what it can say, and what it can’t. Still, while it’s not a surprise that this Disney+ original can’t really answer all the questions that Mickey’s past and present bring to bear, it’s to its credit that doesn’t refrain from asking them. Story of a Mouse is as openly strange and racked with contradictions as the character at its center, and in that sense, it presents a compelling portrait.

You can stream Jeff Malmberg’s Mickey: Story of a Mouse on Disney+ beginning on November 18.

Comments are closed.