In recent years, Copenhagen’s Rigshospitalet was the site of most of the major Danish royalty’s births. Last year, it was ranked the 15th best hospital in the world. It has, at least in name, been around since 1757, and, if you were to stand on the very top of the building, you could see neighboring Sweden, now connected to Denmark by the UN’s E20. It serves as a major hospital for Danes and adjacent Swedes; it also serves as the butt of a joke by a now-repentant Lars von Trier.

When von Trier first made The Kingdom, named after an approximate translation of the hospital’s nickname of “Riget,” he was a young punk of 38, fresh off the successes of The Element of Crime, Epidemic (also filmed at Riget), and Europa, each of which branded the Dane as a European shit-stirrer, but not quite “Lars von Trier.” The Dogme 95 films happened in-between seasons of The Kingdom, and the aesthetic legacy of the movement is embedded in that original series: a harsh yellow putrefies the florescent hospital lights while the camera itself zooms, follows, remains forever mobile. Special effects are tossed aside in favor of naturalistic, implied horror. There’s something supernatural hidden deep in the cracks of Riget, but it can only be hinted at while the bureaucracy of the hospital (a stand-in for the politics of Denmark, and Europe more broadly) slowly collapses. When von Trier released late works such as Melancholia and the great The House That Jack Built, his earlier works including The Kingdom appeared prankish and adolescent — more a simple middle finger than what a middle finger represents.

So, one may expect a new Kingdom to look more mature, or perhaps realize a straightforward reinvention of the series, akin to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, which allowed Lynch’s late style to remix work from a world that doesn’t exist anymore. Though von Trier teases such ambitions, by the first ten minutes of the first episode, we’re clearly back in Riget, where forces older than humanity wouldn’t notice the temporal jump that birthed hi-def digital photography. Instead, the von Trier cinematic universe plays with von Trier’s legacy and pokes fun at the Dogme 95 aesthetics that still dominate this series, now with an unwelcome comparison: verité workplace mockumentary sitcoms such as The Office and Parks and Recreation.

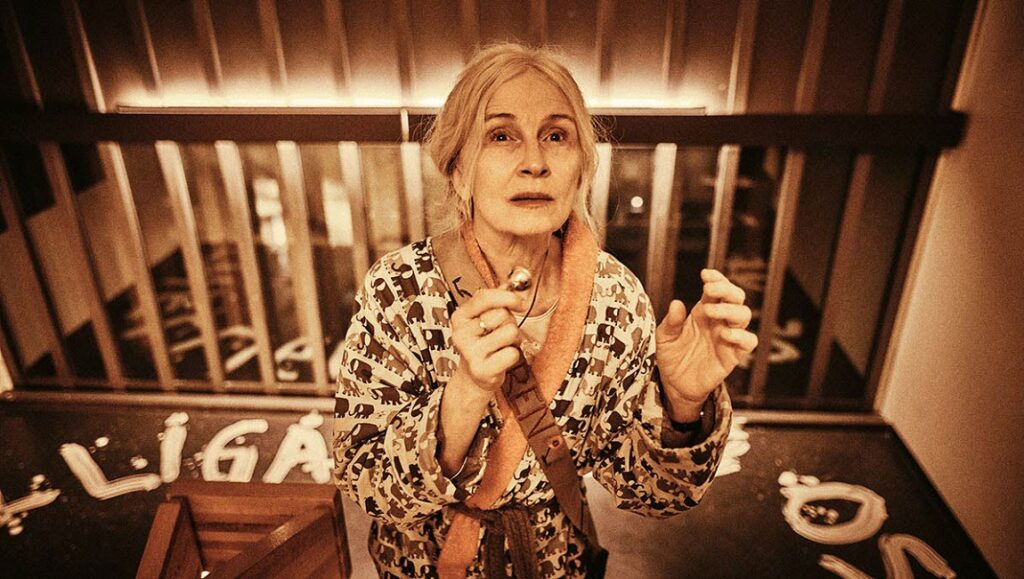

Though it’s hard to imagine von Trier chortling through seasons at a time of Michael Scott’s buffoonery or posting memes about how gosh-darn stubborn that Ron Swanson is, the comfortable American genre is a perfect subject for von Trier to infect with his brand of cynical humor (previous seasons of The Kingdom would have taken American influence from General Hospital or E.R. as much as Twin Peaks). Half of the show is indeed a straightforward(-ish) workplace comedy, mostly focusing on the new Swedish doctor, Dr. Helmer (Mikael Persbrandt), as he shares departmental responsibilities with his despised Danes. The other half explores the darker world of hospitals, mainly through the vehicle of Karen (Bodil Jørgensen, playing her character from The Idiots) who sleepwalks to Riget after finishing (and audibly disliking) The Kingdom on DVD. She’s pulled into a Chamber of Secrets conspiracy surrounding the hospital, full of hidden tunnels, portals, and Satanic doppelgängers. The intro for each episode reminds us that the hospital was built on ancient bleaching grounds, and Karen’s journey, along with her reliable hospital porter (Nicolas Bro, who previously played a hospital porter in Brian De Palma’s Domino), unearths the cursed history of the hospital and its ultimate devilish purpose.

These two plotlines mingle a bit, but ultimately remain separate. Part of the humor comes from how petty the bureaucratic soap opera upstairs looks compared to the horrors through the portal in the basement. Dr. Helmer has personally taken the job to discover what “this country” did to his father, the Dr. Stig Helmer of the previous Kingdom seasons. He views the Danes with a particularly Swedish disdain, immediately accepting a challenge to drink a never-ending amount of liquor during his first minutes on the job to prove his worth, as well as having his mind broken when he discovers the Danes have built a bridge to Sweden — genuinely believing they would not be capable to build a bridgehead. This comes to a comic conclusion in the “Swedes Anonymous” meetings that are exactly what they sound like, each character admitting feeling tortured by simply being away from their king’s country. Though von Trier plays this running gag off as cartoonish (akin, yes, to The Office’s Michael Scott’s inability to navigate his world), The Kingdom remains von Trier’s only explicit statement on his home country and its past, often cribbing elements of Southern Gothic in its more serious moments. A statue of Ogier the Dane reappears throughout the series, often blocking a character from their goal. Ogier, like Riget, has become a nationalist symbol to the Danes, just as Joan of Arc now lives her second life as a symbol of ethnic pride for the French. The statue is menacing, depicting the Song of Roland hero as a stoic sleeping warrior, impossible to light without creating chiaroscuro shadow, distorting his human features into something darker. The statue is said to sleep in his home in Kronborg Castle, growing his beard until Denmark needs him again. Von Trier, not one to shy away from politics, is curiously oblique here as he simply lets the statue, full of right-wing symbolism for a 21st-century Dane, do the talking.

Though Karen’s journey through the hospital’s hell is more Harry Potter than Dante (material he already tackled in The House That Jack Built), von Trier is not interested in his characters “solving” anything. Most of the logic guiding these supernatural forces is poetic, as with the most striking image in the series: Udo Kier’s head. Kier, reprising his role as the ominous-sounding “Little Brother” is visible only from the nose up as he slowly drowns in his own tears. His head is gigantic, but the CGI compositing onto the bleaching ponds is beautiful, thanks to DP Manuel Alberto Claro, who shoots Kier and the ponds as a monochromatic Bosch landscape (a stark difference to his imitating the rough DV photography of the original series during every other scene). Though we’re given hints as to what it means for Kier to hold the keys to the Kingdom, no information given is explicit, and it simply feels right that when this strange creature has drowned, all hell will break loose.

Another welcome cameo comes from Satan’s little helper, Willem Dafoe, who Willem Dafoes his face into various Chiclet-toothed smiles that let us know he is not from this world. Von Trier’s sign-of-the-horns sendoff in the previous series hinted at the Satanic nature of Riget, but it’s never quite clear what all the devil talk is about until the final cameo, Satan himself, appears. It’s a cheeky moment in a series that otherwise pulled punches compared to von Trier’s film work, with von Trier himself admitting as much during the end credits. Perhaps he’s getting older, he opines. Perhaps it’s harder to pull off this series with so many of the original cast now dead. Perhaps von Trier, in and out of hospitals all the time now due to his recent Parkinson’s diagnosis, thought the material too close to home in every possible way. There is no cynical sting like the end of Dancer in the Dark, nor is there the discomfort of Dogville, nor is there the sheer aesthetic bravado of The House That Jack Built. But the characters continue to punish themselves, and von Trier continues to somehow make that a fount of comedy. By the end, he makes it quite clear: we’re all going to hell anyway.

You can currently stream Las Von Trier’s The Kingdom Exodus on Mubi.

Comments are closed.