“A nation that doesn’t know its past, has a dull present and a future shrouded in fog.” So opens Alon Schwarz’s newest participatory documentary film, Tantura, titled after the very massacre it purports as its subject. Already in this initial glance — in contextualizing the proceeding images and investigation — it’s egregiously obvious that the film’s perspective is one engendered by decades of Zionist internalization. Whilst it’s not hard to understand the intention of insinuating a cultural instability wrought by state mediation and violence (which is already center stage of the political landscape in Israel) — where, daily, images witnessing the oppression wrought by the IDF and settlers onto the Palestinian people are disseminated — all this accomplishes is positioning us in the headspace of that age-old lie of morality on which the country has stood since 1948. It skews our approach to this history by suggesting only one perspective: the very one that has sought to revise and erase the Palestinian narrative, which is not unexpectedly but certainly disappointingly absent from this work. In seeking to structure a “human” siphon from which we can glean and discover this story (Schwarz plays, essentially, the protagonist of this film), the director participates in the very suppression he seeks to unveil.

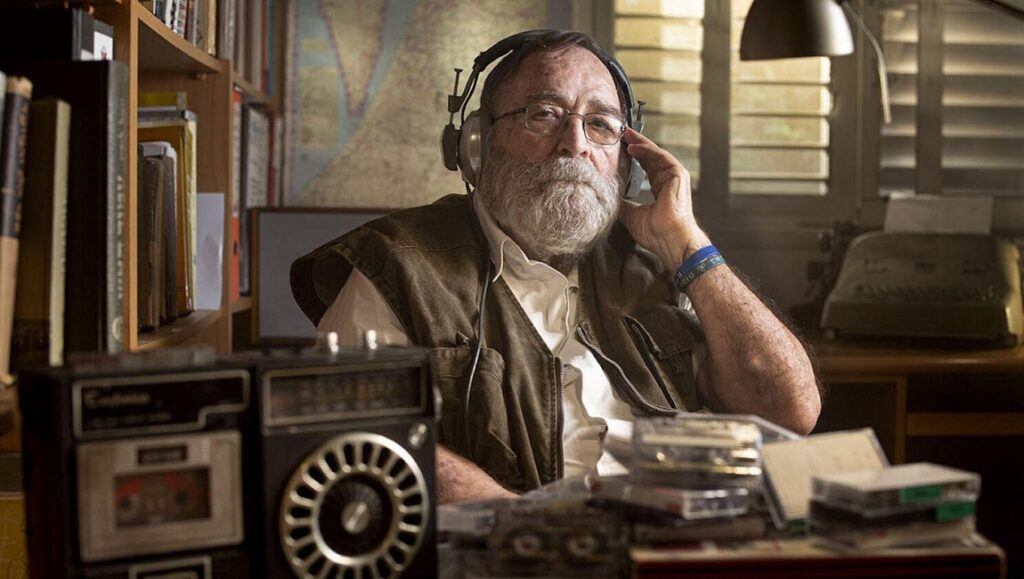

This is not all simply extrapolated from the above opening quote. It is indicative, naturally, of the film itself. For the opening half-hour of this 90-minute film, we spend most of our time learning about Teddy Katz, a former academic who, in 1997, published his thesis on this massacre which, following a publishing of his findings in a local forum, began an outpouring of rage and enforced silence. This subsequently led to his ostracizing and, doubly, lent Israeli society the justification of ignoring the testimonies of their own kin. This is not a narrative about a massacre, but that of the state built atop of it; this is not about a people, their narratives, or their witness accounts that have been shared and known openly for decades throughout the global Palestinian diaspora. This is about a state’s existential crisis, utilizing the subjugation of another people as dressing to interpret a self-sustained ethic. We hear so many rumors, denials: in fact, we spend about as much time with a man who states, “I am considered a radical on this issue, I don’t believe witnesses. And Teddy’s thesis was… about 90% or so based on oral evidence… which is good for folklore but not for history,” as we do on the only two Palestinian witnesses the film meagerly edits in to account for their victimhood. These two individuals, Hend Hawashe and Mustafa Masri, enter the film approximately halfway through.

When Tantura played at Sundance, an article was published — simultaneous to its premiere — by Adam Raz in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, discussing the mass grave under a famous Mediterranean beach through, in its entirety, the perspective of the film. There is no further investigation into that which the film very glaringly disregards. The 2008 documentary by Palestinian filmmaker Arab Loutfi, Over their Dead Bodies: Tantura, the Forgotten Massacre — easily accessible via Youtube — is itself a vital artifact, one easily found with five minutes of probing, in how we approach perspective and in ensuring that the history of research and testimonials taken up by others are not lost. Schwarz’s documentary, conversely, provides enough political doublespeak to engage in it with caution and skepticism, but this all feels like a morbid PR stunt. The timing is all incredibly coincidental and convenient if it is not part of a marketing scheme organized to direct eyes toward the film and, concurrently, a major cultural institution that this year orchestrated an elaborate and mawkishly sensorial land acknowledgment as it programs films such as this which reject indigenous self-sovereignty. An article that purports to reveal to an Israeli mass the findings of a mass grave contextualizes it as follows:

“His documentary film ‘Tantura,’ which will be screened twice this weekend online as part of the Sundance Film festival in Utah, would seem to undo the version that took root following the libel suit and Katz’s apology. Even though the testimonies of the soldiers in the film (some of them recorded by Katz, some by Schwarz) were given in broken sentences, in fragments of confessions, the overall picture is clear: Soldiers in the Alexandroni Brigade massacred unarmed men after the battle had concluded.”

[…]

“The Tantura affair exemplifies the difficulty that soldiers in the 1948 war had in acknowledging the bad behavior that was on display in that war: acts of murder, violence against Arab residents, expulsion and looting.”

[…]

“It’s to be hoped that from the perspective of years, such subjects will be more readily addressed. A possibly encouraging sign in this direction is the fact that the film about Tantura received funding from such mainstream bodies as the Hot cable network and the Israel Film Fund.”

It’s not even worth beginning to expound on why wording such as “bad behavior,” when discussing atrocities, minimizes and exacerbates the dynamics at play. Necessitating pithy form, for Twitter’s character limit stifles more than it permits, user @HashemAbuShama goes semi-viral in accusing the article of colonial practices: “Haaretz’s story on the Tantura massacre is more abt Israeli historiography than it is about the massacred Palestinians. If anything, it demonstrates that colonial perpetrators, colonial academics, and colonial archives are automatically endowed with the authority to ‘narrate.’” This sentiment sums the film up rather elegantly. We are given inter-titles about the wave of criticism against Teddy and what it did to his life, and yet a denier of all Teddy’s evidence is given more time in the film than any of the Palestinian witnesses who have been shown on screen. Of course, Teddy’s story is indicative of the Israeli settler-colonial project: an erasure of the history that proves its colonial intention, and the violence that it has bred, but Tantura is not Teddy Katz’s story. Tantura is the story of those who were forced out of their homes, of those who survived, and of those who survive the loss.

What plays comically in the publishing of this Haaretz article as coupled with the film’s premiere is that it divulges the weakness at the work’s core, often found in most expository, and especially participatory, documentaries: A five-minute read has yielded the same information as the hour-and-a-half watch. The redundancy of the film is purely monotonous. To intervene in this, Schwarz has conceived of a participatory angle, where we unearth these awful truths alongside him — he positions himself as audience and investigator, as scrutinizer and learner. This dynamic, as mentioned above, isolates how we access this history, how we perceive its legacy. We are entirely segregated from the horrors, subsumed by a normalization that is aptly spouted by one of the film’s subjects: “But it happened, what can you do? It happened.” The film has little interest in the massacre itself; it has little interest in Tantura. This is a film about the intransigence of Israeli and worldwide Zionist ignorance — even apathy.

It is undoubtedly true that the accounts we hear in this film are shocking, that the doublespeak, the passivity, and even pride that these anecdotes are presented with are maddening and abhorrent, from the rape of a young woman and the murder of her uncle who stood to protect her, to the indiscriminate grenades that flew into the houses of Tantura residents of the time — these fragments in the larger narrative of the massacre are horrifying, yet they are treated like plotting, a build-up, which is where one must inquire, ultimately and inevitably, on the ethics of the processes of documentary filmmaking and the narrativization of history. This is at the head of discourse within documentary communities, and when an example of a film so unintentionally tainted in absent-minded trivialization comes around, it’s difficult not to agree with such austere allegations as those of aestheticism. What is the utility in transforming the expansive events of the Nakba into a 90-minute narrative? Is this the amount of time we need to understand what happened, what ensued, and what persists? Is this not a practice of efficiency and reduction, narrativizing, creating protagonists and supplementary antagonists to streamline a history that is not really even ours? I grew up being told that this was our history, but it cannot be — we made it ours, and with films such as this, we continue to. Capping off the second act of Tantura, we are informed of two things: that Ben Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, enacted a project in the ’50s that would “prove” that the Palestinians, during the Nakba, left on their own accord; and that the IDF (Israeli Defence League, the state army) archives will not release “material that may be harmful to the image of the IDF as an occupying army devoid of moral foundations” — these are the words of IDF officials, themselves; official government wording. There is no doubt that this had happened. Even with their attempts to cover this up, they cannot skirt around this burning bush. And so we may ask once again: why all this focus on the Israeli narrative? We are 25 minutes from the end at this point… what is this film supposed to be doing? Who is it for?

It all ends rather unceremoniously. A narrative with a poor third act — shocking. Most obviously, and to no one’s surprise, the ending is more curious in the cynicism that exudes from the perspective of deniers and perpetrators than anything else. To Jews, if this does anything at all, it is most obtrusively and negligibly to offer a contradiction. A dissonance in the evergreen minimizing done to the Nakba, and a dissonance that hinges itself on the self-victimization of a Zionist national through the Holocaust industry. And so, it must be asked again: Where does that position those they, in fact, deny? Does it not negate their primacy and narrative in favor of our own, the very weapon used against them as exposed by the film? Who is Tantura for, and are any answers to this question not already ill-fated to the Israeli supremacy that the film is an active agent of? “Now, to each his morality, to each his interpretations.” — this is a film that fails the history it masquerades as Israeli in nature, a work lost to the state project of global abstraction and erasure.

Comments are closed.