Given that found-footage films comprise their own subgenre of experimental cinema, we might say that — within that category — there exists an even smaller, more specific subset. That subset is composed of films that are essentially close examinations of a particular piece of footage, resulting in works that turn the documentary process in on itself, producing films that essentially ask us to relearn how to see historical footage. There are certain key works that established this sub-subgenre, including Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929), Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (1969), and various films by Yervant Gianikian and the late Angela Ricci Lucchi, the best known of which is probably their 1987 look at cinematic colonialism, From the Pole to the Equator. Today, this strain remains a vital form of analytical filmmaking, as seen in the found-footage documentaries of Sergei Loznitsa or in Three Minutes — A Lengthening.

Private Footage, by first-time director Janaína Nagata, takes this approach in an entirely new direction, one that is bold but not entirely successful. The film is built around nineteen minutes of 16mm film that Nagata acquired when purchasing a take-up reel. As it turns out, this “private footage” was shot in Apartheid-era South Africa, much of it apparently comprised of home movies shot by an upper-level government functionary. While Nagata does not work to identify the man whose family repeatedly appears in the film (especially during the first half, which depicts a vacation in the coastal city of Durban), she does zero in on a great many images and details in the footage, conducting seemingly real-time research to explore the various historical resonances of this otherwise negligible film.

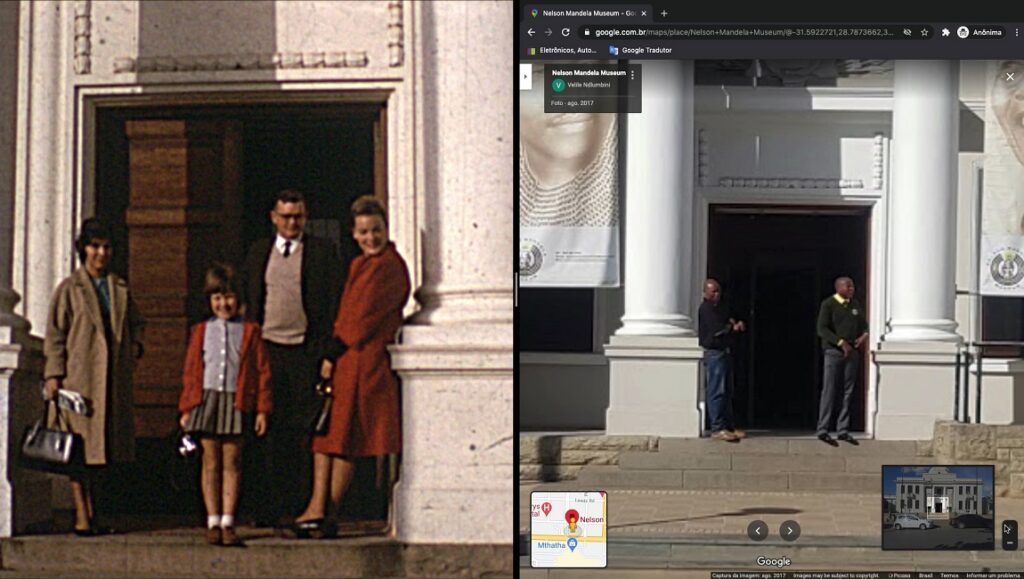

After screening the original footage in its entirety, Nagata employs a split-screen computer desktop composition, whereby she plays the film on the left-hand side of the screen while opening various windows and programs on the right side. This allows her to conduct searches on place and company names, use a facial recognition search engine to identify various figures in the footage, and introduce outside media — interviews, news reports, and other archival material — to create a broader context for what we are seeing play out on the left.

The result is strangely reminiscent of the deconstructed foodstuffs of haute cuisine. Nagata isn’t producing a documentary so much as displaying all of the research process that would ordinarily serve as the background for a nonfiction essay film. At first, this seems novel, as Nagata pauses the found footage and, for example, opens Wikipedia or Google Maps on the other side of the desktop. But eventually, it becomes maddening, as the filmmaker shows herself searching YouTube, then playing a clip without even clicking to close the pop-up ads. At one point, Nagata hits a paywall for a site she’s using and purchases the program in the middle of her work. Private Footage actually shows Nagata entering her full credit card number, including expiry and CVV. It’s truly bizarre.

The film does introduce compelling historical background regarding the life and career of “architect of Apartheid,” H.F. Verwoerd, as well as his informal advisor, a millionaire Bantu “witch doctor” by the name of Khotso Sethuntsa. A more conventional approach might have been to locate these men in the footage and then extrapolate outward, showing the wider impact that they had on South African history and culture. But Private Footage seems to have other interests, such as trying to display the current state of online investigation, performing the “deep dive” that the Internet permits. This is a distraction at best, a gimmick at worst, and suggests that we’ve been watching notes toward a documentary rather than the thing itself.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 18.

Comments are closed.