Maestro

When the 2018 remake of old Hollywood standby A Star is Born dropped, it marked the culmination of over a decade’s worth of effort to update the well-worn tale into something that might entice modern audiences. At its helm was first-time feature film director Bradley Cooper who, up until that point, had enjoyed leading man status for the likes of David O. Russell and Cameron Crowe, while also playing a number of slimeballs and scumbags for Todd Phillips and various, like-minded studio comedy journeymen. Though some inevitably expressed skepticism over The Hangover stars’ ability to make the filmmaking leap, and many others invested in the Lady Gaga of it all, A Star is Born ‘18 proved to be such a commercial and critical success that the question of Cooper’s auteur status would have to be entertained.

But, more importantly, 2018 also brought us The Mule, Clint Eastwood’s 37th feature as director and his second collaboration with Cooper, following their bold, controversial take on American Sniper’s Chris Kyle. Far less fraught than that film, The Mule is one of Eastwood’s numerous end-of-life/career elegiacs with a meta-hook, the director casting himself alongside actual family members in a final, melancholic attempt at redemption which includes a passing-of-the-torch moment between the screen legend and his apparent protege — Cooper. This gesture made sense when taken alongside A Star is Born, a project inherited from Eastwood that probably (and not so coincidentally) strongly resembled his work, with its efficient visual stylings and thematic pursuits, akin to something like Million Dollar Baby or Honkytonk Man. But while Cooper was able to successfully riff on Clint’s template for his debut, it makes sense that he’d go bigger with his follow-up — the Scorsese-and-Spielberg-produced Leonard Bernstein biopic, Maestro — although he may have been a bit hasty in casting off that dependable Eastwoodian restraint.

Performing as understudy to his iconic producers — both considered directing the project themselves at some point in recent years — Cooper once again assumes responsibility behind the camera and in front of it, effectively channeling the reckless, joyful spirit (and intense narcissism) of Bernstein, whose fast-talking charm and assured genius fit into the actor’s skill set comfortably. Covering the bulk of Bernstein’s professional career as conductor and composer, Maestro hems in the scope of this incredible life by framing its narrative around his relationship with actress Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan). Bernstein, a barely closeted gay man, and Montealegre, a straight woman, are drawn together at a party by chance; fascinated and compelled by one another, they quickly fall in love and agree to marry. Of course, their love for each other isn’t exactly symmetrical, and though Montealegre believes in her husband’s genius and thinks she can accept his relationships with men on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” basis, the weight of her sacrifices and his neglect eventually grind her down, a sort of cancer the film implies eventually metastasizes to the lung.

Cooper attempts the high-wire act of appealing to the living children of his subjects (i.e., the estate), while also depicting Bernstein honestly and artfully, but he’s ultimately undone by this challenge, falling into a number of biopic-specific traps along the way (clumsy expository dialogue, undermining dramaturgy in favor of chronology, etc.). Maestro isn’t a totally starry-eyed depiction of Bernstein by any means, but the way it apologizes for and redeems him via his wife’s battle with cancer feels unsatisfying and evasive, and at odds with what Cooper (and Mulligan) seemed to be angling for up till the film’s three-quarter mark. Otherwise an odd mishmash of stylistic choices — the first quarter or so attempts to approximate the aesthetics of a then-contemporary Hollywood musical, to dubious, annoying effect — largely informed by Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz and Lenny, one can see just enough of Cooper in the film (mostly thanks to his stellar performance) such that Maestro isn’t a total wash, but he gets lost among the warring voices and sensibilities at play here, with most things about the production marred by a sense of uncertainty. One could imagine a sturdier, more focused version of Maestro in line with Eastwood’s downbeat anti-musical Jersey Boys, or the manic sadness of his Charlie Parker biopic Bird (or better still, J. Edgar, a film that interrogates its subject in ways this one can’t), which feel like they’re very much in Cooper’s wheelhouse. The film we have received, though, suggests maybe we don’t really understand what that means for this filmmaker yet, and perhaps, neither does he. — M.G. MAILLOUX

Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros

For most of Frederick Wiseman’s career, the master documentarian has focused on the lives and institutions of the United States. His films have painted a nearly 60-year developmental portrait of an evolving America, full of imagined utopias (Aspen), too-real dystopias (Public Housing), and the flawed systems that… [Previously Published Full Review] — ZACH LEWIS

The Beast

“You were to suffer your fate. That was not necessarily to know it.” So declares May Bartram to John Marcher, both doomed lovers of Henry James’ epochal novella, The Beast in the Jungle. Doomed they are, however, not as lovers, but as precisely those for whom love proves elusive and impossible; and May does not quite declare this utterance, sibylline, so much as she pronounces it in retrospect and with regret. The obsessive panic and portending of doom, for James, necessarily precludes foreknowledge of it, and it’s this cruelest of ironies which he inflicts on the suffering celibate along with his hopeless beloved. The parallels with history cannot be clearer: Kierkegaard’s injunction of faith in “looking forward,” Hegel’s tempering of the dialectic in that Minervan owl which “spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk,” Sloterdijk’s diagnosis of the twentieth century as that insatiable search for ineluctable Truth — instantiated not as reality, but as ideology — all point to the terrible paradox between living and knowing, a conflict of will and thought played out endlessly in the theaters of wars and death camps. Between the individual and the world, there lie a multitude of selfsame conflicts, each preoccupied with telling their story whilst living it.

This desire to narrativize reflects a desire for control which, in most filmic adaptations of James’ text, presents itself rather conservatively; i.e., through the light ballroom steps and dancerly grace meant to both reflect and literalize the author’s florid linguistic constructions. Such confinement of textual source to its genre locale, though not undue, risks squandering the rich ambiguity of his prose for prosaic, stultifying interpretations; Patric Chiha’s eponymous version, for instance, does mesmerize with its “lush, hypnotic, if sometimes impassive rendition of a Parisian nightclub as liminal, timeless space,” but invites little more than academic scrutiny from those already keen on Jamesian allusion and neuroticism. In what will be rightly viewed as the novella’s most radical adaptation thus far, however, the French filmmaker Bertrand Bonello transposes the tale of John and May onto a dazzling canvas — spanning three time periods across two centuries — over which fate and history are, like Apollo and Dionysus, diametrically opposed yet cunningly aligned. Arguably the most faithful adaptation put to screen as well, The Beast finds its fidelity mediated through its towering novelty, announcing a bleak and sterilized future where emotions are dead, historical time is confined, and past lives have become accessible for the purpose of bodily catharsis.

Against this twilit backdrop, two souls emerge, having always known each other. In 1910 Paris, Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) meets Louis (George MacKay) at a ball and confides in him her premonition of a formless but deadly beast, entreating him to keep watch over when it should pounce. Gabrielle, a musician wedded to a enterprising dollmaker, faces her enlivened reality with languid imagination, hovering over her Belle Époque-milieu in a kind of trance: the great floods of that year are on arrival’s cusp, and the likes of Schoenberg and Stravinsky will soon revolutionize, then render vulnerable, the horizon of musical expression. Louis, likewise a member of Parisian high society, intercedes — first through a spiritual medium, the better to anticipate the future with, and then with his hand, professing a love which Gabrielle unhappily rejects. The beast, naturally, is this refusal of love, that fear of consummation that strikes them amid a torrent of flood and flame. John and May, their sexes now inverted, continuously strive and continuously fail to achieve the literary grandeur promised them by their time; the age of Modernism, as it were, heralds tremulous premonitions but withholds their breathless cadences from materializing.

Slightly over a century later, in 2014, the beast strikes again — Gabrielle, now an aspiring model in Los Angeles, soaks in its balmy afternoons and cacophonous nightlife whilst house-sitting in a resplendent abode; Louis, her star-crossed lover, appears in the periphery, looming menacingly with stocky build and vengeful countenance. “I only have sex in my dreams,” he announces, recording his life’s will and administering his last rites in front of a camera, malice and wounded pride swirling within and about to be unleashed in a blaze of cold fury. Reminiscent of the gunman Elliot Rodger, Louis forgoes celibacy this time not voluntarily, but unwillingly and arguably out of a penetrating fear of loving another. The “beautiful things in this chaos,” which Gabrielle tries in vain to convince him of, still inhere despite a century’s worth of upheaval and disillusionment. Past the gilded hallways of Parisian boudoirs, from some past life of hers, remain traces of action and intention (a table, a knife, an unseen threat), albeit conjured through greenscreen fog. If the 20th century was, in Merleau-Ponty’s view, an age of embodiment, the 21st teeters over into the zone of disembodiment, its digital smears and pixelated mirages conferring an excess of reality upon reality itself; the decline of the West, as popularly and calamitously intuited, follows from this rupture, while dread and the inevitable become one.

The third act of The Beast takes place in 2044, some years removed from the present day but curiously entangled with the latter’s preoccupations and nascent realities. High tension has made way for an aseptic nostalgia, and history and time have properly stopped. Paris, once again, comes under the camera’s mellow gaze, although this gaze has been emptied, stripped of vital substance. Under the hollow afternoon sun, the city’s vacant streets recall mausoleums, monumental in their dead vainglory; artificial intelligence has sought the total rationalization of society and consecrated the atomization of its individuals. Gabrielle, made anew, is out of work and in search of purpose, which she finds with a state-mandated caveat of emotional purification. She must purge the residue of her past lives, and in doing so re-enter life as homo economicus, trading in breathless stupefactions for airtight ones. “Nothing can happen to us now. The catastrophe is behind us,” parrot her contemporaries. Chancing upon Louis at the purification center, she meets him again at a dance floor, its changing years the simulacra for an eternal present. Through lives and deaths and life once more, the pair are united.

But this unity is fraught, of course; how could it not be? Bonello’s signifiers are numerous, but two most prominent are his figures of motion and stasis: the flight of the pigeon and the indifference of the doll. Flight is doom’s harbinger; indifference its tacit acceptance. Slowly, creeping through the ages, they settle, and in settling, enslave the lovers to their dispassion. Premonition, made sublunary thus, is proclaimed over in Bonello’s daringly sci-fi tour de force, the soul having been materially extracted and yielded over to empiricism. In The Beast, such empiricism first proves reactionary — amid the global crises of identity politics and sexual hedonism in 2014 — and then rote, when history, already ended in 2044, resurrects its marionettes one last time to expunge them. What Bonello realizes so radically throughout these interwoven periods is how the malaise of the present forever haunts its visions of the future, just as how the future has always arrived, is always the age of unattainable nostalgia for the light. With stylistic precision and visual panache, he fashions a haunting metaphysical reverie of the human soul, condemned to meaning it cannot decipher. Gabrielle, musing over the transition from porcelain to celluloid dolls in old Paris, becomes a doll herself in the city of broken dreams: substituting last-minute as the lead for a road safety commercial, she mounts a rig, is hoisted onto a slab by an imaginary vehicle, and collapses, frozen. “You’re dead!” the director tells her. “Don’t move. You are dead.”

Death, for the denizens in The Beast as with James’, renounces fear and catastrophe, whereas life itself is the openness toward them. A counterpoint to mainstream Jamesian exegesis — which attributes John’s reticence to his queerness — may be found in Eugene Goodheart’s reading of The Beast in the Jungle, arguing that “what May knew,” namely, the “aesthetic consciousness” of John to which James affixes her undying devotion, constitutes the work’s underlying bestial tangent. Within this moral order, the stubborn aesthete finds solace through preservation; sentiment and emotion, which Schoenberg would develop to heart-stirring effect in his string sextet “Verklärte Nacht,” have little place here. But precisely because Bonello flirts with doomed love, his Dionysian personae are just as headstrong, just as staunch in their tempestuous embrace of asceticism untamed. They — Louis initially, as socialite, and then Gabrielle, as postlapsarian lamb — seek out, just as the prodigal Thomasina does in Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, the twin flames of wisdom and passion, echoing the lithe dolls of Bonello’s 2011 House of Tolerance: “If we don’t burn, how will the night be lit?” But the lit night is an Arcadian fantasy, evoked in the throes of certain ruin. “When it’s evergreen, evergreen / It will last through the summer and winter too,” croons Roy Orbison, his sentimental ballad fittingly installed, in the closing minutes, over the lovers’ dance of death. It is a dance of immense aching, of loving and fear, and of the ones we fear only because we love them the most. — MORRIS YANG

Allensworth

Since moving from 16mm to digital nearly fifteen years ago, James Benning’s films have become more and more stringent, foregoing surface incident in favor of intensive examination of the outside world. The freedom to make the films he wants, whenever and wherever he wants, has led to a… [Previously Published Full Review] — MICHAEL SICINSKI

In Our Day

Hong Sang-soo’s second film of 2023 — and 30th overall in a 27-year career — premieres just a few short months after in water at Berlinale. That film found Hong investigating the nature and process of making cinema, both in general and in his own idiosyncratic manner. It was a bit of an experiment, of course, being filmed, to varying... [Previously Published Full Review] — SEAN GILMAN

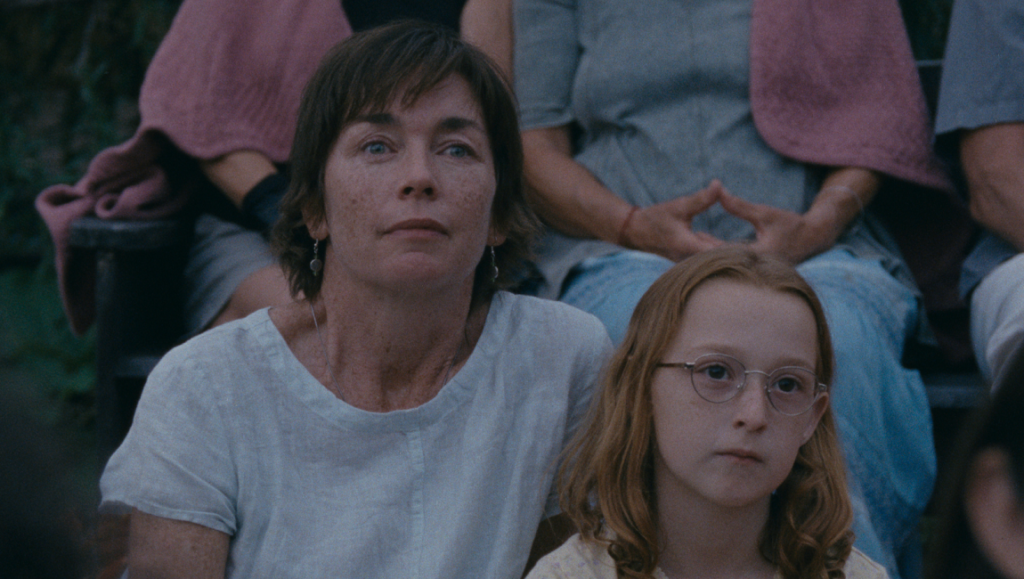

Janet Planet

A mother and daughter’s symbiotic bond fuels the artistic crucible that underlies Janet Planet. Such a description, let alone the title, might indicate a film that’s merely riding the coattails of Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird. Fortunately, Annie Baker’s first foray into feature filmmaking is anything but derivative. The facility for naturalistic dialogue seen in her plays has found a suitable medium in cinema for accentuating the actions of ordinary people who either don’t entirely grasp the words needed to articulate their feelings, or don’t know those words well enough to remain silent.

11-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler) belongs to the former camp, with the added caveat that she often says the wrong thing at the wrong time. Her demands in the film’s opening moments to be taken home from summer camp, lest she commits suicide, are fulfilled, but she regrets her actions upon realizing that some of her fellow campers will miss her. “I thought nobody liked me, but I was wrong,” Lacy tells her mother Janet (Julianne Nicholson) in a desperate gambit to reverse course. Janet doesn’t take the bait, and the pair return to their rural Massachusetts home, and to mom’s boyfriend Wayne (Will Patton), to spend the rest of the summer of 1991 together.

Enumerating the events in the plot would do a disservice to the way Baker and her actors economically reveal information about their characters. We learn that Janet runs an acupuncture clinic in her home, which gives the film its name, yet the only client we see is Wayne when he’s seized by a crippling migraine. We gradually glean from Janet’s nurturing tendency a pattern of caring for damaged men, rooted in a difficult relationship with her Holocaust survivor father. But Baker doesn’t reduce Lacy and Janet’s codependency to this spate of exposition, allowing Ziegler and Nicholson’s chemistry to accord their relationship a sense of close, if not always healthy, intimacy.

Baker introduces several characters whose presence quietly provokes Lacy and Janet’s dynamic, including an old friend, Regina (Sophie Okonedo), and a spiritual guru, Avi (Elias Koteas). These peripheral figures in Lacy’s life provide an impact which she does not fully grasp in the present. With its protracted, static shots, the analogue cinematography by Maria von Hausswolf emphasizes moments of contemplation for children and adults alike with tactile immediacy. The significance of these reflections, primarily held by women, lies in their potential for personal revelation.

These moments are also rife with potential rupture, and Baker’s conversations possess these multiple possibilities. A nighttime parlay with Regina swiftly turns sour when she tells Janet that she makes bad decisions. The latter, who believes some people are incapable of telling the difference between good or bad choices, turns coldly furious, and her hostility is subsumed by Lacy. This duality is literalized, perhaps a little too neatly, in the Red Riding Hood doll owned by Lacy’s piano teacher, which can morph into the grandmother and Big Bad Wolf.

By and large, Baker avoids rendering objects with pat allegorical import. For example, the small figurines and detritus that dot the tiny stage in Lacy’s room are mementoes in the constructed play of her memory. Indeed, the image of a child overlooking “the little world” of the stage is redolent of nothing less than Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander. Baker earns the comparison without resorting to facile pastiche, as the film’s climactic moment also incorporates an enigmatic disappearance that teases the outer limits of magical realism without breaking its own inimitably cast spell.

As Avi tries wooing Janet by reciting Rilke’s Elegies, the passage he quotes gestures toward a transcendental love children have that requires their parents to ebb “into cosmic space.” By letting go of a parental bond, children are given the chance to make their mark on the world, even if that mark is ultimately ephemeral. But what elevates Janet Planet to a superlative bildungsroman is Baker’s wise understanding of how the constituent pieces of those marks are culled from those we’ve loved and hurt. “Can I have a piece of you?” Lacy asks her mother. Growing up means watching the piece of our parents we receive transfigured into new material, and with all the self-love we can muster identifying that piece as a part of ourselves. Sharing that with others, in all of its ambivalence, is central to Baker’s artistic ethos. — NICK KOUHI

A Prince

Pierre Creton’s acclaimed 2017 documentary Va, Toto! was, among other things, an examination of the lives of elderly gay men in rural France, depicting their aging bodies as they work the land, and one another. Creton brings this subject matter into the fictional realm with A Prince, a film that… [Previously Published Full Review] — MICHAEL SICINSKI

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed

Many critics have already labeled Joanna Armow’s laboriously titled The Feeling That the Time For Doing Something Has Passed a “millennial” comedy (a fitting alternate title: Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time), a descriptor that makes a certain amount of sense but that also feels limiting. It’s true that… [Previously Published Full Review] — DANIEL GORMAN

Man in Black

In many respects, each of the works by Wang Bing at Cannes this year exemplify the now reigning axes of Wang’s interests and style. Youth (Spring) is the latest embodiment, in now sparser and more controlled form, of what West of the Tracks: Tie Xi Qu (2002) established, Crude Oil (2007) (for want of a better word) refined, and 15 Hours (2017) crystallized, in terms of… [Previously Published Full Review] — SEAN GILMAN

The Shadowless Tower

Chinese-Korean director Zhang Lu has been a bit of a slow burn in the West. Despite having directed 12 feature films since 2003, only a handful have made waves on the broader film circuit. These include two early works, Grain in Ear (2005) and Dooman River (2011), and most recently Yanagawa (2021), which received a lightning-quick U.S. theatrical release — Zhang’s first. Even competition slots at two high-profiles — Desert Dream (2007) in Berlin, and Gyeongju (2014) in Locarno — did surprisingly little to increase his visibility.

It’s possible that this will change with his latest film, The Shadowless Tower, which also competed in Berlin earlier this year. To call a work of cinema “novelistic” is often to damn with faint praise, suggesting that the filmmaker has sacrificed filmic considerations in order to foreground a narrative structure better suited to another medium. But like the best “novelistic” films — one thinks of Yi Yi (2000) and Drive My Car (2021) — The Shadowless Tower communicates complex states of being through framing, camera movement, and the accretion of detail over time. Although Zhang’s style has been consistently patient and meticulous, he has achieved something of a higher order with this new film, his literary and directorial instincts achieving an ideal harmony.

At the center of The Shadowless Tower, narratively speaking, is Gu Wentong (Xin Baiqing), a middle-aged divorcee eking out a living in Beijing as an online food critic. His life is in the permanent doldrums, and his only moments of unadulterated happiness are spent with his four-year-old daughter Smiley (Wang Yiwen). But for reasons left largely unexplained, apart from vague references to how “busy” Gu is, Smiley lives with Gu’s older sister Wenhui (Li Qinqin) and her husband (Wang Hongwei). Over time, we see that Gu is both too financially insecure and — frankly — too depressed to be a full-time father, much to his shame.

But that shame, like so much else in The Shadowless Tower, is almost wholly internalized. For a writer, Gu has a deeply ambivalent relationship with words. Frequently, he follows an utterance by saying “that’s not what I meant,” as if wanting to retract a statement even before making it. At many points, characters chide Gu for being “too polite,” which is code for passive-aggressive diffidence. While some viewers may struggle with Zhang’s leisurely pacing and the subtle precision of Piao Songri’s camerawork, this style and atmosphere perfectly reflect the stop-and-start aimlessness of this man whose identity seems to have cratered when his marriage fell apart. This is nowhere as evident as in Gu’s inscrutable relationship with Ouyang (Huang Yao), the 25-year-old photographer who shoots the food for his reviews. They are together constantly, and at various points she tries to initiate a sexual relationship, or maybe more, with Gu, to no avail. At other times, they spar like frenemies, and in still other moments, they tell strangers they are father and daughter, which is quite plausible given their age gap.

What Gu and Ouyang actually do share is a primal wound that neither will directly address. When he was five, Gu’s father (played by Fifth Generation titan Tian Zhuangzhuang) was forced to leave his family behind. We learn that he came by on the kids’ birthdays to gaze at them secretly through a window, and after finding the old man’s address, Gu lurks around his father’s home staring at him. Ouyang, meanwhile, has her own daddy issues, and it is to Zhang’s great credit that he allows Gu and Ouyang to hover around each other like charged particles, their relationship never succumbing to cliché.

But while Gu is central to the film narratively speaking, the true geographical center of The Shadowless Tower is the White Pagoda, a 13th-century structure that, it is said, casts its shadow many miles away in Tibet, but leaves no such impression in Beijing. This architectural anomaly speaks to the complicated place of Buddhism in the People’s Republic, but Zhang, even more than this, allows it to serve as a looming metaphor for a solitary life, for people who — for whatever reason — refrain from making their presence felt in the lives of others. Such a hulking symbol could have been unbearably clumsy, with all the negative connotations of literary impulses clashing with cinematic expression. But like so much else in this film, the actual Shadowless Tower simply stands there, obdurate in its brute physicality. But everything is always moving, and The Shadowless Tower marks time like a sundial, whether its characters see it or not. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

About Dry Grasses

When first introduced in About Dry Grasses, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s latest feature, Samet (Deniz Celiloğlu), an art teacher, has been in the remote village of Icesu for four years. Posted there for compulsory civil service, he has been looking to leave since the moment he arrived — and by the end of the film, he will do so. Before the… [Previously Published Full Review] — LAWRENCE GARCIA

The Taste of Things

Trần Anh Hùng’s The Pot-au-Feu charts a romance between gourmet chef Dodin Bouffant (Benoit Magimel) and his cook, Eugenie (Juliette Binoche), in late 18th-century France. Their relationship as creative collaborators and lovers sidesteps the typical pitfalls of complicated entanglement or fraught power dynamics, Hùng instead taking… [Previously Published Full Review.] — EMILIO DIAZ

Bleat

After dipping his toes in the waters of English-language filmmaking, Yorgos Lanthimos makes his return to his Greek roots with Bleat, inviting a cadre of international collaborators — notably, his current muse Emma Stone — to participate in a piece commissioned by the National Greek Opera for their Artist on the Composer program. Tasked with putting a classical piece of music to film, Lanthimos and his team have produced a curious spiritual parable devoid of sound, but teeming with familiar images of aberrant sexuality.

A small, exclusively female enclave on an unnamed island (Lanthimos shot the film on the 75-square-mile island of Tinos) congregates for a funeral. They are mourning the only man among their flock, whose widow (Emma Stone) is their youngest member. Tight close-ups of Stone’s face rhyme with the wizened faces and hands of her peers, a communal vision belied by a prevailing specter of mortality. Upon their departure, Stone’s face gradually cracks into a fissure of sorrow as she regains her composure on the brink of tears. Stone’s mechanically precise transition between the polarities of grief is striking, and more than a little disquieting, for the discipline she displays in a scenario of which, ostensibly, she has little control.

Yet she transgresses the boundaries limning life and death by resurrecting her husband through a spontaneous bout of necro-cunnilingus, sealed with a none-so-subtle lick of a portrait of Jesus hanging above the bed. Without expounding upon the rest of the plot, the man (Damien Bonnard) partakes in an unorthodox inversion of a wedding ceremony. Lanthimos has cited Macedonian Wedding, Takis Kanellopoulos’ 1960 documentary short, as an influence on Bleat’s second half. Kanellopoulos infused ethnography with a poetic romanticism, as his camera tracked in and around villagers celebrating long-standing East Macedonian and Greek customs. For his part, Lanthimos is less interested in cultural specificity than in doffing his cap to one of the prominent figures of Greek Cinema’s Golden Age.

With its other cinematic precedents and touchstones, Bleat splits the difference between the ecumenical austerity of Dreyer and the comparatively secular sacrilege of Keaton. Lanthimos’ insistence on screening the film on 35mm with live orchestral accompaniment only doubles down on this formal invocation of silent cinema. But as made evident by his two previous collaborations with Stone, he freely appropriates historical signifiers into a postmodern cocktail that vaguely gestures toward universal aphorisms. As the final minutes of the film unfold, they approximate an aura of rapturous awe that only yields a manufactured miracle.

If the spiritual dimensions of Bleat feel overly calculated, that may be because Lanthimos is a filmmaker who’s more comfortable in the realm of the senses. Goats aptly abound throughout the film, occupying a metaphorical parallel to the human figures driving the wisp-thin plot. Their presence calls attention to the peculiarity of human behavior, yet the brutal fate of one poor bovid seems distinctly informed by a vestigial echo of Greek antiquity. In this respect, Bleat yields a flash of historical specificity that’s refreshing in the wake of the director’s burgeoning overreliance on anachronism.

If the film’s offbeat pleasures are greater than the sum of their parts, then those pleasures are provided by the game artists who have helped Lanthimos realize his vision. This writer had the good fortune of seeing the film in Alice Tully Hall with an orchestra performing the accompanying pieces by J.S. Bach, Toshio Hosokawa, and Knut Nystedt. Lanthimos wished all of the musicians good luck before the screening — “Hope you do a good job!” were his words — but he needn’t have worried: their clockwork precision invigorated Thodoros Mihopoulos’ stark monochrome photography with ethereal beauty. Even if the film’s parting shot of collective transcendence rings hollow, the choir that sang over the ending instilled enough hushed awe, its voices joined in polyphonic grace. — NICK KOUHI

Orlando, My Political Biography

Berlinale’s Encounters section has largely been a platform for lesser known filmmakers since its inception, though it’s also seen its fair share of high profile directors, including Bertrand Bonello, Cristi Puiu, and Hong Sang-soo. This year Hong is joined by Paul B. Preciado, a prominent… [Previously Published Full Review.] — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER

“>

Comments are closed.