Scénarios

The last image of Jean-Luc Godard’s last film Scénarios is one of the most heartbreaking in his long, storied, notorious, glorious, defining, essential career. It is of Godard sitting on his bed, his shirt open, taking notes on a film he will never make. “Okay,” says a woman off-screen — presumably Anne-Marie Miéville, Godard’s partner in love and cinema since the ‘70s — and that is the last we will ever see of Jean-Luc, the screen goes black, and the man who vigorously redefined the possibilities of cinema time and time again since 1960 is now dead. This image is more devastating than that of just seeing a monumental figure in his twilight as a man, but it’s also the way that it’s shot that tears one’s heart out: smoothly steadied by hand with a wide-open aperture, this is an image Godard would have never filmed himself.

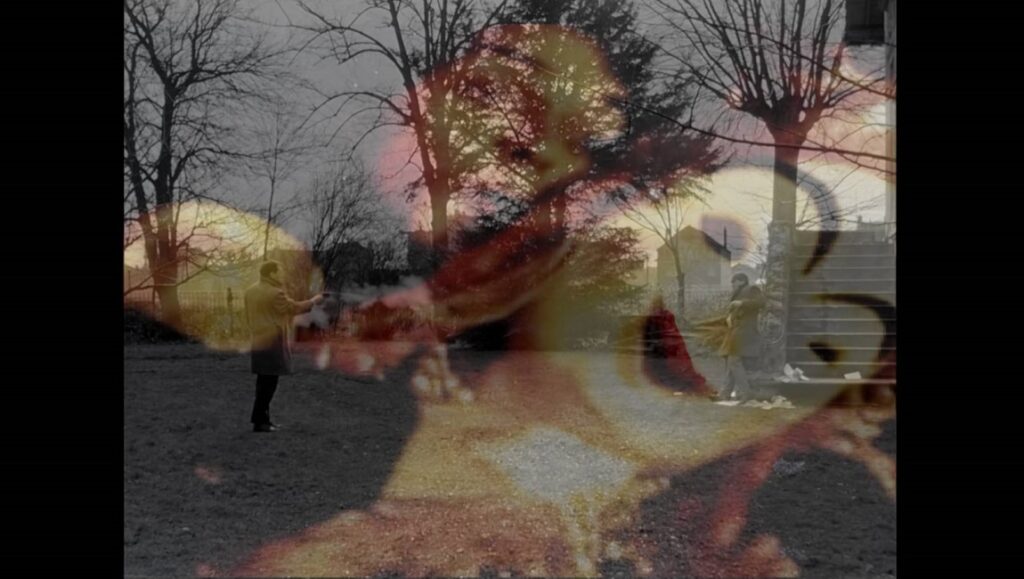

Godard built and rebuilt a unique mise en scène for himself in the post-New Wave stages of his career, the decades that really mattered. In the ‘70s, it was video work, multi-screen scenes and images directly laid in contrast to each other. In the ‘80s, his camera locked down on a tripod, exposing as much depth of field as possible while filling modern hotels and old chateaus with natural light. Hybrid video became Godard’s masterworking in the ‘90s — not just the recollecting of images, but the reconquering of them, reframing to take on new worlds of meaning. In the 2000s, his digital took on a new light, most stunningly with his cut to color in In Praise of Love (2001), where the black-and-white world of film is suddenly dunked in sharp blues and oranges that bleed out their own details. He’d expand this digital texture even further into the 2010s, ripping apart the images with 3D in Goodbye to Language (2014) and making a final screed in The Image Book (2018). What little he left in the 2020s were not images themselves, but notes on images, paintings over them and diagrams of the future. Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: ‘Phony Wars’ (2023) is a collage film — not in the “conventional” avant-garde sense of images overlayed each other in motion, but a film made up of images of collages that Godard produced for the never-completed film Phony Wars. Godard’s voice in Trailer is confident, if physically failing in his frail old-age. In Scénarios, it feels like Godard can barely speak, the reach of his still-sharp mind exceeding the grasp of his body. Even more than Trailer, Scénarios is less a film made by Godard than one his collaborators are trying to finish for him.

Scénarios opens with an image scrolling right-left across the screen, a photograph painted over by Godard’s own hand — the quality of the image being conquered by the material overlay of the artist. That kind of reconfiguring is typical of Godard, whose truest, fullest masterpiece, Histoire(s) du cinema (1989-99), is chock-full of the pieces of cinema overlapping, digitally altered, re-graded for new effect, as if the images themselves that made up the 20th century were being filtered through the director’s emotional memory of them. In Scénarios, the images we see are crisp. When Godard constructs a sequence in the latter minutes of Scénarios — piecing together a woman getting killed in Jaws (1975), a roadside assassination in the Middle East, the mirror shootout in The Lady From Shanghai (1947), Bridgette Bardot’s body hanging out of a crashed, cherry-red sports car in Contempt (1963), the doomed flight at the start of Only Angels Have Wings (1939), bodies on the highway in Weekend (1967), and, of course, Anna Magnani in Rome, Open City (1945) — the pictures are almost always of the highest quality transfers available, which does not feel Godardian, especially not in his latter stages. But interestingly, this sequence concludes with what seems to be a photo of a dead child, printed for maximum contrast, where any grays fade into their respective blacks and whites. Perhaps this is the way Godard instructed the image to be shown, perhaps it was an image in this quality when he left it behind, and perhaps even Godard didn’t reconstitute the cinema images because he didn’t have the time or the energy before his death. Or maybe those working to finish the film to the best of Godard’s intent didn’t see themselves fit to attempt to do it themselves.

Regardless of its ultimate presentation, what is left behind are final thoughts, the things that peeked out of Godard’s memories in his last days. Sometimes they elude the viewer. Why is it that, of all of Godard’s films, the two he wishes to revisit at length in Scénarios are Germany Year Ninety-Nine Zero (1991) — the sequence when Eddie Constantine (reprising his Lemmy Caution role) and a policeman knock on a window of a group of women playing violins — and the final shootout in Band of Outsiders (1964), which Godard was known to cite as being one of his worst films? One can feel something he’s trying to dig at emotionally, although it’s tough to find the words for what exactly that is. Much clearer in reason, if unexpected, is Godard’s use of a specific quote: “In the bowels of a dead planet, an ancient mechanism quivers,” from the Canadian science fiction author A. E. van Vogt’s story “Defense” this writer is indebted to Raymond Bellour for pinpointing this obscure citation), and which Godard first used in The Power of Speech (1988). Importantly, this quote is a translation of a translation: van Vogt’s original reads, “In the bowels of the dead planet, tired old machinery stirred,” which is rather dry compared to the poetics of the French versions: “Dans les entrailles de la planète morte, un antique mécanisme fatigué frémit.” The first half is the same when brought back to English, but it is undeniable that “an ancient mechanism quivers” is more beautiful and evocative than “tired old machinery stirred.” This translation (and re-translation) evokes the quivering (or, more literally from “frémit,” “shuddering”) film running, be that through a camera or a projector, dancing through the reels. This plays twice, as well, complementing the opening R-L scroll, literally running the film back. Though darkness is setting in on the world, the movies still play, again and again, until there is not enough light left to expose an emulsion or all the projector bulbs have burned out.

So whirs the projector at the Walter Reade Theater after Godard has gone out for good. Where Trailer felt like a transmission from the dead, Scénarios and the behind-the-scenes type film Exposé du film annonce du film Scénario (and, no, the film in Exposé is not the film Scénarios we just saw, it is a different film entirely, one that will only exist in notes and remembrances of Jean-Luc’s explanations) are films that show us really just how long Godard has been dead. He passed just over a year before Israel began its genocide in Gaza, and knowing of the lifelong importance the liberation of Palestine was to Godard — he’s recounted before that it was the political cause that brought him and Miéville together — it’s unthinkable to imagine that this would be anything other than Godard’s chief contemporary concern. In 1968, he helped shut down Cannes because he thought the Revolution was here; in 2024, there were protests to boycott the New York Film Festival entirely due to some of Lincoln Center’s donors’ Zionist beliefs. What this writer felt in the room watching Scénarios was that Godard was indeed dead. I felt the “here” and “elsewhere” Godard and Miéville sharply dissected in 1976 with Ici et ailleurs. The “elsewhere” is a world of constant destruction, humiliation, genocidal fury, and death, while the “here” is one unending stream of those violent images, resonating throughout the years like seeing Anna Magnani getting gunned down by Nazis juxtaposed with contemporary strife. “Here” we’re in a dark room watching the shadows of ghosts dance along the walls. “Elsewhere” people are on the streets. — ALEX LEI

April

There’s a moment smack in the middle of Beginning, Georgian director Dea Kulumbegashvili’s formally astute but callously cruel debut feature film about the combined oppressive forces of religion and patriarchy slowly but surely crushing the spirit of a depressed, devout woman, that threatens to expand not only her worldview but also the film’s. It involves her going to her mother’s house after we see her get brutally raped by an evil man in a static wide shot, its needlessly elongated duration recalling the infamous rape sequence from Gaspar Noé’s aggravating Irréversible. Kulumbegashvili provides no such time for the interaction between mother and daughter, which may as well be the point. Our protagonist, a member of the Jehovah’s Witness community, is defined by the violence committed against her, not her loud or even quiet rebellion against it; seeing other women, like her mother, living a similarly cloistered and repressed existence makes her accept her submissive attitude even more — except when she sees her younger sister, who has only recently become a mother, also follow the same trend. She’s puzzled by her sister’s decision to have a child this early in her life (we’re never explicitly told how old she is; the film implies that the younger sister would have just begun college if not for the birth of her child); she’s disappointed that her sister has left her education for a child whose “father hasn’t realized yet he [even] has a child.”

This feeling of quiet rebellion against patriarchy, briefly ignited by this sequence but largely left unexpressed in Beginning, materializes into something much more mysterious and altogether more potent in Kulumbegashvili’s second feature, April. In a way, it’s almost confrontationally oppositional to her first film’s turgid passivity. Here, our protagonist, Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili), is most defiantly an active participant: she’s an obstetrician in rural Georgia willing to aid patients seeking abortions despite legal prohibitions against it. Her moral stance, made repeatedly clear throughout April, is that “if it’s not me, it’ll be someone else.” But does she really believe that? Kulumbegashvili consistently contrasts her defiance with her downbeat existence, which, in theory, feels like a natural extension of Beginning’s monotonous miserabilism. Here, however, it doesn’t feel like the director is merely using cruelty as a form of artistic currency; Nina’s seemingly self-imposed isolation and sexual masochism complicate the genuineness of her beliefs. It almost feels like she has internalized the “murderer” tag given to her by those who condemn illegal abortions. So, detachment – from any genuine human connection – becomes her form of self-punishment.

The most impressive aspect of April — which sets it apart from other similarly punishing and horrifying pro-abortion dramas like Vera Drake (2004) and 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days (2007) — is its aesthetically varied depictions of Nina’s alienation. It’s surprising, too, since Kulumbegashvili could have easily resorted to doubling down on the tried-and-tested aesthetics of the European art film she gained plaudits for in Beginning. April still features that Haneke-styled boxed-in framing whose shot duration can feel punishingly long and unnecessarily emotionally distancing. But, given that our protagonist is much more of an active participant in the film’s drama, it also features movement. Kulumbegashvili and cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan signify this formally by switching from static shot compositions to handheld camerawork. They rely on this most in sequences when Nina is traveling away from the hospital’s cold sterility to either perform abortions in a village or engage in her nocturnal sexual adventures-cum-humiliations. The camera not only follows her here, but it embodies her POV, making her appear a bit like Scarlett Johannson in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin: a wandering alien (or ghost) engulfed by unnaturally loud sounds of heavy breathing and entrapped by the beautifully stark Georgian hellscape.

Kulumbegashvili further leans into this lo-fi surrealism in sequences that push April into the realm of an abstract creature feature. Unlike the change in shooting style, there’s no discernable explanation for the radical shift in generic form here. These sequences that bookend the film and pop up unannounced throughout it work as haunting folklorish interludes: otherworldly visions of a future (or past) version of Nina as a monster covered in moldy, decomposing flesh seemingly trying to express her repressed feelings — of guilt, love, and loneliness — through her increasingly decaying body language. Or as the arthouse equivalent of Bollywood musical numbers: an unexpected expression and underlining of every feeling Sukhitashvili’s cryptic performance of Nina otherwise keeps concealed. Whatever the intended rationale — and it may not amount to either of these for different viewers — the critical thing is that Kulumbegashvili’s aesthetic experimentations leave an emotional impression. Nina’s helplessness and isolation — self-imposed, state-enforced, or both — is palpably felt in April, not, as in Beginning, just forensically examined. — DHRUV GOYAL

Caught by the Tides

In 2001, Jia Zhangke made Unknown Pleasures, in which Zhao Tao plays a woman named Qiao Qiao who tries to make a living as a singer and model while juggling the attentions of her abusive agent Qiao San (played by Li Zhubin), her young boyfriend Xiao Ji, and Xiao’s friend Guo Bin. The film is set in the northern Chinese city of Datong, about five hours north of Jia’s hometown, Fenyang.

In 2006, Jia Zhangke made Still Life, shot in the last days of the dismantling of the city of Fengjie, soon to be flooded as a result of the Three Gorges Dam project. Zhao Tao plays Shen Hong, a nurse searching the town for her estranged husband, Guo Bin (played by Li Zhubin). She eventually finds him, but it seems he’s been up to no good: shady real estate dealings, sending gangs of kids to fight other gangs, romancing a corrupt politician — so she ditches him.

In 2018, Jia Zhangke made Ash is Purest White, which is set over three time periods. It begins with footage leftover from Unknown Pleasures, but quickly moves to new material and introduces Zhao Tao as a woman named Zhao Qiao who, along with her husband Guo Bin (played by Liao Fan), are medium-level gangsters in the city of Datong. In its second third, the film shifts to Fengjie, where Jia mixes in leftover footage from Still Life. Zhao is in town again searching for Guo Bin, who has been engaged in shady business dealings. They meet and break up. In the final third, Guo returns to Datong after suffering a stroke, where Zhao wearily takes care of him.

In 2024, Jia Zhangke has made Caught by the Tides, which is set over three time periods. It begins with footage from Unknown Pleasures, some of it outtakes, some of it repeated from the earlier film. Zhao Tao plays Qiao Qiao, an aspiring actress and model who is in a relationship with her agent. He’s again played by Li Zhubin, but he’s now named Guo Bin. After a fight, Guo texts her that he’s off to make his fortune and disappears. In its second third, the film shifts to Fengjie, where Jia mixes in leftover footage from Still Life. Zhao is in town searching for Guo Bin, who has been engaged in shady business dealings, including sending gangs of kids to fight other gangs and dating a corrupt politician, so she ditches him. In its final third, Guo returns to Datong after suffering a stroke, where he and Qiao reunite.

What are we to make of these rhymes and repetitions? Why is it that in Jia Zhangke’s films, we are presented with an infinite variety of Zhao Taos, but those Zhaos are perennially stuck with losers named Guo Bin who don’t deserve her? Actually, that’s not much of a question: the fact that Zhao is Jia’s wife should explain it. Caught by the Tides’ remixing of old material can be partially explained by practical reasons: shooting during Covid would limit the scale and time Jia and his crew could devote to a new project. But it’s tough to fully buy into that: plenty of Chinese filmmakers have been able to make wholly new movies over the past four years without scavenging the outtakes of their past work.

Rather, the simpler explanation is that Jia is getting older, and one of the things that happens when you get old is that you spend a lot more time thinking about your past than you do going out there to create new memories. He made Unknown Pleasures as his third feature film, when he was 31 years old. It’s not unexpected that he would constantly think about other ways he could have made it, other directions its story could have gone. It was a film that consciously set out to capture a new generation of Chinese youth, kids who had grown up completely in the post-Cultural Revolution era, when China was rapidly modernizing and, to some extent, Westernizing. In 2006, with Still Life, Jia found the perfect symbolic representation of the effects of that modernization in the crumbling city of Fengjie.

Ever since Jia returned to fiction filmmaking after a seven-year absence (during which time he made a handful of documentaries), his films have been episodic attempts to capture a wide swath of modern China. A Touch of Sin combined real-life news reports of scattered tragedies with the conventions of wuxia and other genre fiction in an attempt to link China’s seemingly alienated present to its long and complex history. The three films after that are split into thirds, spanning from 2001 to the mid-2000s to the present to the near future. Mountains May Depart created new stories and characters for each of its timelines, while Ash and Tides reconfigure Jia’s previous work. Where Sin took wuxia as its referent, Ash used Heroic Bloodshed cinema, tracking the difference between gangsters who followed the form of the Chow Yun-fat heroes they idolized and those who truly upheld the honorable ideas the films espoused. Tides, though, is nothing more or less than a romance: a missed chance followed by grave mistakes, with the hope of reconciliation and atonement to come with the wisdom of age.

Mountains was widely criticized (mostly unfairly, in this writer’s opinion) for its depiction of the next generation in the form of Zhao Tao’s character’s son. It seems likely that Jia, realizing he is no longer connected to the youth of China, has retreated to the safety of his middle-aged memories, content to refashion his past and mine it for new potential resonances, rather than attempt to capture a younger generation he really doesn’t understand anymore. This may explain why, given that in the middle third of Tides, set in 2006, Guo Bin is said to be 32 years old, but in the section set in 2022, he appears much older than 48. I’m 48, and while I don’t look that old either, believe me, I feel like it every time I try to figure out what these kids today are up to and why.

Tides feels like an attempt at summarization, a way to close the book on a chapter of Jia’s filmmaking before (hopefully) moving on to new and original products. The movie it reminds most of (aside from Jia’s own films, of course) is Adam Curtis’ It Felt Like a Kiss, which similarly reconfigured the director’s last decade or so of work, but distilled down to its essence. Just as Tides is shorn of most conventional dialogue or characterization, Kiss does away with Curtis’ famous narration: both movies instead make extensive use of title cards to explain necessary information, but otherwise rely on music and images to convey their stories.

Mountains begins and ends with the sound of waves crashing, the opening sounds of the Pet Shop Boys’ cover of “Go West” and also possibly a reference to Zhao Tao’s given name, which means “waves”. Tides begins and ends with the sound of wind blowing. Both the wind and the waves are expressions of motion, ironic for a filmmaker who seems stuck in his moment. Ash is Purest White gets its title metaphor from a volcano, the heat of the earth purifying its heroine’s soul. Looking to the future, Jia has given us UFOs and transparent iPads and talking robots. Will he find new elements for his movies as well? — SEAN GILMAN

Harvest

Athina Rachel Tsangari’s newest film, Harvest, begins on the precipice of change. Based on Jim Crace’s novel of the same name, Tsangari’s adaptation is set over the course of seven days “around Shakespeare’s time” in an unnamed English village following the Enclosure Acts. Led by Walter Thirsk (Caleb Landry Jones), whose sleepy voiceover washes over the film, we watch as the common land shifts hands from small farmers to wealthy landowners. Tsangari’s film is punctuated by anxiety, violence, and absence, and in so doing evokes a sliver of time — between the feudal system and industrialization — in European history, one which has been since lost to privatization.

A loose hierarchy is quickly established in Harvest. Walter is first seen traversing the landscape with gusto rather than working in the fields. Draped in blue, he sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the greenery, fingering tree hollows and eating bark before swimming naked in the lake. No one else is seen, until the camera pulls away from Walter and his nature-loving endeavors. Through effective long shots, we can see that the village resembles Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s busy compositions. This is partially because the village is in a fit of chaos and the barn is on fire, but also because the village is littered with allegories as in Bruegel’s work. Walter and Master Charles Kent (Harry Melling), his oldest friend and confidant, are both former townsmen. In the past, Walter served as Master Charles’ manservant, so he can read and write, unlike the other villagers, while Master Charles controls the lay of the land and its future developments.

Unlike Walter and Master Charles, who frolic through the fields as individuals, most of the villagers stick together as a collective, condensed unit. Their lives are not easy. Through their daily routines, songs, and conversations, we learn that the villagers depend on gleaning from Master Charles’ fields after they are commercially harvested. The leftovers from the common land are then distributed according to need, but this system is on the brink of change, and Tsangari uses this to build a pervasive sense of anxiety into the film, one heightened by a cacophony of non-diegetic music hammered into the narrative and Sean Price Williams’ cinematography, which ladles increasing distress onto the mounting unease via shocking, grainy closeups of dirty hands, mud, and carnage. He spends time documenting the villagers’ movement from near and far by combining drone footage with handheld shots that are edited together in rapid fashion. These camera angles add a healthy dose of modernity to Harvest that takes away from the film’s “Peasant Bruegel” aesthetic, but these choices are intentional. Rather than leaning into the Terrence Malick approach to composing landscapes, which feature vast, ethereal tableaux, Williams’ cinematography is fleeting and schizophrenic, of the same spirit as the villagers’ last days on Master Charles’ land.

But, of course, the villagers do not welcome outsiders. Three vagrants are quickly captured and blamed for the fire at the beginning of the film. A woman, Mistress Bedlam (Thalissa Teixeira), has her hair forcibly shorn for the village’s enjoyment while two men spend a week in the pillory. In Crace’s novel, Walter learns that the tree vagrants were forced from their village when it began focusing on sheep-herding rather than farming. This fact is omitted from the film, but complicated by Tsangari, who employs non-white actors in two of these roles, making their presence even more unwanted by the xenophobic villagers. The arrival of Phillip “Mr. Quill” Earle (Arinzé Kene) has a similar effect. Hired as a cartographer, Mr. Quill makes a lay of the undocumented land with Walter’s help. Mr. Quill is overcome by the land’s beauty and Walter’s knowledge of all things great and small, including the border rocks which kids’ heads are thumped against so “they know where they belong.” During one languid scene, they forage weeds and flowers; “naming things is your way of knowing things,” states Mr. Quill, leaving Walter aghast. Unfortunately, Mr. Quill’s benevolence toward the land will not save him. His status is in limbo, partially because his map prefigures the village’s new ownership, but also because he’s Black.

Despite the film’s narrative action, which slowly ramps up after Mistress Bedlam’s arrival, Walter keeps things sleepy. His voiceover reveals his innermost thoughts, which are benign and funny at best. At one point, during a sex scene with Kitty Gosse (Rosy McEwen), he wonders if they are even friends as she flops around on top of him, showcasing his neutrality toward women, and perhaps the villagers in general. He and Master Charles are the most similar characters. They look like they are from the Middle Ages and don peasant attire despite their privilege, but they never really walk the walk. When Master Charles’ cousin Edmund Jourdan (Frank Dillane) shows up in black robes, like the Devil himself, neither Walter nor Master Charles makes a stand for the village, even after a group of women are kidnapped and presumably raped by Edmund’s henchmen. Walter functions as a passive bystander, his moral compass magnetized. He simply watches as the film’s events take place, staring into the distance without saying a word.

In many ways, then, Harvest is deceptive. Rather than being a film about abundance, it’s a tragedy about erasure and absence, and something of a survey of xenophobia thanks to Tsangari’s casting. The Enclosure Acts, and the ensuing agricultural shifts, are a result of the first waves of early Capitalism, thus causing fear and anxiety in the village, two themes that permeate the film. Unfortunately, no one, including our ostensible protagonist, harbors much sympathy for long. Walter’s passivity leaves him alone at the end of the road. Rejected, he thumps his head against the border rocks, accepting his fate. He belongs with the land, and the past, while everybody else moves on. — CLARA CUCCARO

The Suit

It has now been seven years since Heinz Emigholz, until 2017 mainly known for his semi-silent architecture films, reintroduced language into his cinema with Streetscapes [Dialogue]. That film, structured as a series of conversations between an artist (John Erdman) and his psychoanalyst (Jonathan Perel), was inspired by Emigholz’s own depression-fueled sessions and thus served as a form of autobiography and auto-critique, building in discussions of the filmmaker’s career to date. Since then, Emigholz has collaborated with Erdman thrice more: first in The Last City (2020), which unfolds as a set of disparate conversations, and then in The Lobby (2020), where Erdman is credited as Old White Male, and which plays more like a misanthropic theatrical monologue. Like Streetscapes before it, The Suit, their latest collaboration, enfolds knowledge of those prior films into its diegesis — and Old White Male isn’t happy with the results.

For one thing, he contends that if anything, The Lobby was not misanthropic enough. For another, he is decidedly displeased with the label Old White Male, as if he could be reduced to an age and ethnicity. But then, he finds fault with virtually everything, at one point flatly remarking, “I no longer enjoy living.” (One of the few things he expresses admiration for is the suit he wore during the filming of The Lobby, hence the title of this film.) Perhaps unsurprisingly, Old White Male lives alone in a bunker, where he is surrounded by books, contemplates suicide, and dreads what is to come. More surprisingly, he receives a video call from his future self.

Unlike The Lobby, then, The Suit is undeniably verbose, but not technically a monologue. As in all of this recent cycle of films, Emigholz breaks up the presentation of speech and dialogue across a variety of spaces — and this remains the fundamental interest of the film. The additional fillip here is the disorientation that results from this cross-temporal conversation. If Streetscapes, for all of its visual interest, conforms to the beats of a psychoanalysis session, The Suit goes a step further by depicting a conversation with oneself, thereby dramatizing the discontinuity involved in a passage from present to future. Apart from the structural interest of that move, however, The Suit comes across less as a standalone film than as the latest in an experimental cycle. Caught somewhere between the daisy-chained dialogues of The Last City and the oppressive but charged atmosphere of The Lobby, it is a transitional work that leaves tantalizingly open where exactly Emigholz is heading. — LAWRENCE GARCIA

Fire of Wind

Fire of Wind is the surreal debut feature from Portuguese filmmaker Marta Mateus, which opens presumably in the present, as workers pick grapes in the summer sun and before one woman cuts her hand. We follow her trail of blood among the leaves and discarded feathers, until we find her again in a tree — trapped up there by a bull on the loose. The rest of the workers, and many faces and hands we haven’t seen also climb up, creating a whole world in the trees as night sets in. Mateus cuts from face to face, body to body, as they monologue amongst the branches, the raging bull kicking up leaves behind them. The film becomes a direct metaphor: of course the people need to return to the ground, to their fields, yet they are forced to live in constant precarity and a state of seeking refuge. From that vantage, all they do is watch.

Mateus uses an ample amount of reflected light, redirecting the sun’s beams against itself, creating harsh illuminations and flash-like portraiture in both broad daylight and night sequences. It is at first quite subtle: a grapevine a little brighter than it should be with its back lighting, or the space between bushels having a soft spotlight between its shadows. At first it could be mistaken for amateurish lighting, but as night sets in, its intentionality becomes clear; clear too is that it is the effect of a confident filmmaker. This kind of illumination feels indebted to the contemporary master of Portuguese cinema (and perhaps European cinema as a whole), Pedro Costa. Mateus is not merely a borrowing, however, but also delivering a bold iteration. Whereas Costa is often remembered for his interiors, Mateus stages her film entirely outside, showing us a strange world within the trees. Meteus’ world too is atemporal and aspacial — where the physical continuity of a space isn’t as important as its emotional contrasts, where people in wedding dresses can be seated in trunks near modern workers or soldiers from a war in the distant past.

Fire of Wind’s emphasis on the naturalistic is in stark contrast to all that looms around it. Deep in the night of the film, lights creep up over the horizon. A combine harvester cuts through the orchard at night. The peasants watch from the trees. “Nobody knows the land anymore, there are machines for everything.” The juxtaposition of a monstrous mechanism ripping up all the grapes that were so delicately cut by the hands of the workers is a brief moment in the movie’s runtime, but leaves a massive scar — as violent as the bull but oddly more indifferent. Even running from the bull, it seems natural to reach for the trees. But in the onlooking of modernity from distant groves, there is nothing but silent helplessness as far-off things sever connections with the physicality of the earth. Even if their labor was demanding to the point of being backbreaking, it was certainly not a world of alienation, one where the workers now find themselves unable to even plant their feet back on the ground. — ALEX LEI

Comments are closed.