In his essential Jerry Lewis essay “The Jerriad: A Clown Painting,” film critic B. Kite discusses the lineage of classic clowns like Chaplin, Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy, saying: “The great comedians are metaphysicians. Through their relations with space and interactions with the material world, each embodies a mode of being and intimates a deeper (dis)order.” Taiwanese master Tsai Ming-liang may not be a comedian in the way we understand those figures, but he nonetheless carries on in that tradition. Indeed, his 1998 masterpiece The Hole is the apotheosis of this metaphysical tendency. It’s no surprise, then, that over the course of his career, Tsai has frequently been compared to Keaton. Like The Great Stone Face, he’s found a stable, recurring presence in lead actor Lee Kang-Sheng, who has figured in every one of the director’s narrative features, and in The Hole plays an unnamed man who comes into contact with his downstairs neighbour (Yang Kuei-mei) because of a plumbing problem. In the process of being fixed, this results in a small opening in his floor (i.e. her ceiling), leading to all manner of minor irritations and aggressions between the two, a situation Tsai often sketches as one would a silent-era gag. (A particularly amusing sequence has Lee and Yang each making a desultory dinner of instant noodles, their movements just out of sync because, owing to some unknown problem, the building’s tap water is only available in one of their apartments at a time.) Furthermore, as in a Keaton movie, The Hole sees a variety of objects employed to peculiar ends, their received purposes rejected in favor of brisk necessity: an umbrella becomes a receptacle for concrete debris; a wok cover and a kitchen door are used as fans; an ever-growing mound of toilet paper packages turns into a makeshift bed.

This, in a sense, is why Tsai’s great motif is water, which is fluidity, flux, and transformation—but also entropy, dissolution, and decay.

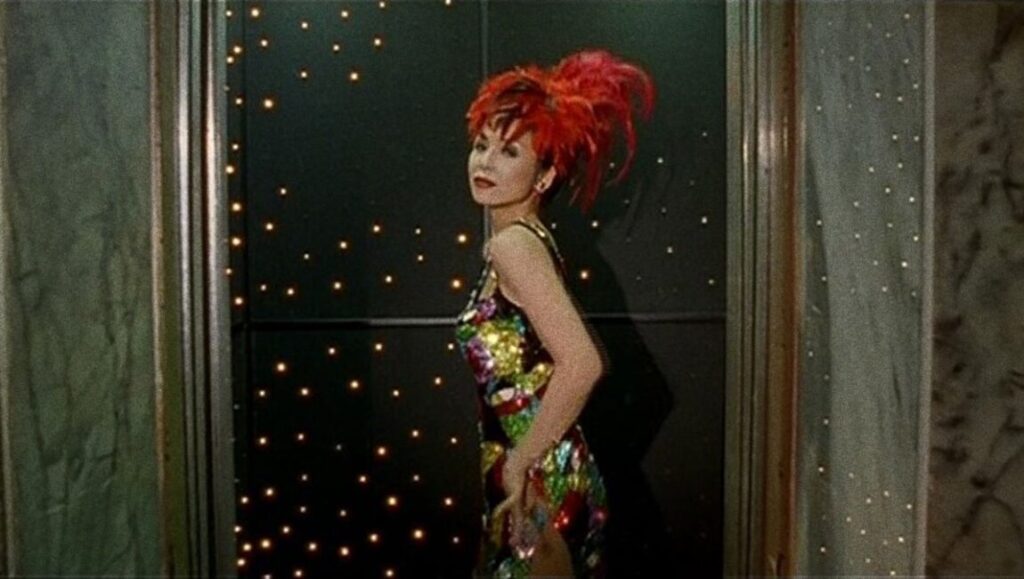

The crucial difference, though, is that whereas Keaton eventually triumphs with such resourceful shifts in usage, thus “click[ing] into gear with the world-machine,” per B. Kite, no such success is ever in store for Tsai’s alienated figures. In The Hole, as in the rest of his films, the world-machine is not just broken, but rusting. This, in a sense, is why Tsai’s great motif is water, which is fluidity, flux, and transformation—but also entropy, dissolution, and decay. As if extending Lee’s chronic neck pain in his previous feature The River, The Hole unfolds in a Taiwan gripped by an uncontrollable epidemic: aerosols and deadly fumigation diffuse into the air; garbage bags seem to fall continually out of the sky; a damp apartment practically sheds its skin. There’s a pervasive sense of alienation that’s mirrored, too, in Tsai’s formal approach, which establishes visual rhymes and subtle linkages between shots (thereby maintaining the narrative momentum of his largely dialogue-free films), while also employing compositions that underline the fixed boundaries of the frame (thus highlighting the ontological limitations of his chosen artistic medium). What comes through most strongly in The Hole is a sense of inescapable malaise, of disease that simply seeps into the bones. For the classic Keaton hero, even the destructive climactic storm of Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) is something to be dodged and overcome. Here, the rain never stops. So maybe all that one can do is sing: The major innovation of The Hole is its inclusion of musical numbers (homages to the film star Grace Chang), each performed with gusto amidst ghostly corridors and crumbling structural facades, a disjunction that Tsai would carry on into the The Wayward Cloud (his second musical) and even into his later digital period with Stray Dogs (2013), whose shots seem to stretch out into infinity. But in The Hole, at least, there’s a certain transcendent finality: Its last shot sees Lee and Yang embracing, at long last, in a barren apartment, swaying to Chang’s lilting voice as the rains continue to fall, and the walls weep around them.

Comments are closed.