Mariner of the Mountains is a beautiful family project that becomes diluted within the context of Aïnouz’s filmography, slowing the film’s considerable poetry.

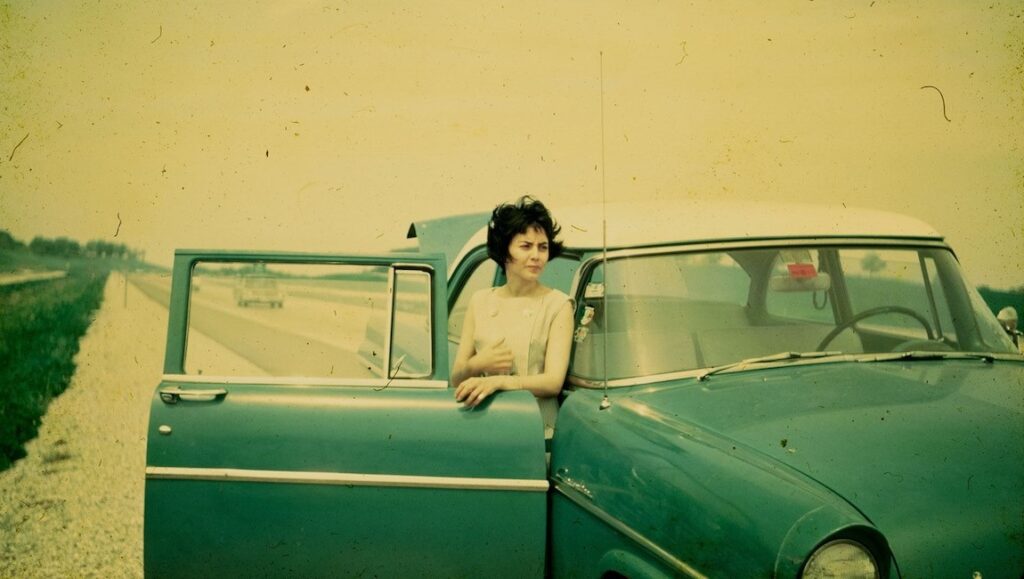

Per the film’s opening titles, calentura, of Latin root, denotes the quality of being warm. Referring to the phrenic, feverish nights of mariners, brought to the deck at night and sighting meadows and white flowers upon the crests of waves, the term has been used over the centuries of seafaring; the mad sailors, caught in a feverish lust for life, are the titular mariners of mountains, sailing over imagined crests of hills in a place they can only dream of. Karim Aïnouz considers himself one of them — less a sailor than a wanderer, assembling a fantasy of his father’s homeland and the mountains he could have known as his own in another life. A letter to a mother he recently lost, and a father he never knew, Mariner of the Mountains is an exercise in unfolding a familial history out of the lineage of entire nations. Aïnouz travels to his father’s Algeria for the first time in the summer of 2019, and high up in the Atlas mountains, a region denoted Kabylia, he meets extended family and finds the birthright into a society freed from French colonial rule. From green-glowing microorganisms to soldiers fighting for independence, all of this living and breathing world is taken in through the eyes of a child for the first time.

Aïnouz is a notedly skilled melodramatist, and these emotive stylings present in two of his best-known fiction features, Love for Sale and Invisible Life, carry their weight in the visuals alone. Red filters, heavy grain, fragmented light, and the splicing of archival footage of both military occupation and revolutionaries side by side displace our eyes with the same disorienting effect the journey to the unseen homeland has. Mariner of the Mountains plays with the idea of a duo, once upon a time the same but now living disparate lives, not quite an analogue to the sisters of Invisible Life but valuable as a recurring theme. In Algeria, the director meets another man by the name of Karim Aïnouz, and it is this doppelgänger that prompts him to envision the alternate existence he would have led had his father not left their family before his birth. A young girl is by the documentarian’s side through much of this trip, offering to hold his camera; one of many subjects, ranging from children on the street to a goat with long, curling horns and a sneering smile, centrally framed and locking eyes with their unseen audience. We, whether standing from the vantage point of Brazil or the perspective of the director’s mother, are meant to meet eyes with Algeria, to survey it in all its living geography. The travel diary form is brought to life well because it never falls into empty musings on a place — there is a clear reconnection with genealogy, of a place held in firm reverence.

Mariner of the Mountains is not intended as a standalone film, and its partner within a dyad with Nardjes A is what significantly weakens the project. Having screened at the Berlinale in 2020, the latter follows a day in the life of a young activist, shot on a smartphone for International Women’s Day. Barring Aïnouz’s lush imagery and rich character studies, what’s troubling with this precursor is how little it actually engages with the politics it tapes experientially, merely celebrating the act of being present in Algeria without delving into its political dimensions (of legislature, pacifist mentalities, etc.). The director considers this minor work of his to be a sequel in his connection drawn between Algeria and Brazil, but there is a sour taste left knowing that this minor work, whose footing it struggles to find, is part of the poetic image of Mariner of the Mountains. What works beautifully as a personal family project becomes, given this contextual incursion, somewhat diluted, a poetry in motion slowed down by its counterpart’s pat verses.

You can currently stream Karim Aïnouz’s Mariner of the Mountains on Mubi.

Originally published as part of Cannes Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 6.

Comments are closed.