There’s a wistful touch of George Bailey to the fatefully doomed protagonist of The Executioner (El Verdugo): José Luis is a Spanish undertaker yearning to go to Germany and become a mechanic, a man with big dreams of escaping his morbid career as each and every circumstance ushers him in the other direction. To think of it, there’s even a bit of Capra-like sweetness to Luis García Berlanga’s satiric scalpel. This quality sets the beloved Spanish director (whose cutting filmography recently made its long overdue debut on the Criterion Channel) apart from his towering contemporary Luis Buñuel, who while just as playful, rarely conceals his viperous bite. On the other hand, Berlanga’s approach is sneakier, all smiles and avuncular glad-handing — often personified by Pepe Isbert’s terrific comedic performances. There’s such a lighthearted grace to his films that sometimes you don’t even notice the poison creeping into the bloodstream. This delicious sleight of hand is how Berlanga slipped one of the most caustic satires of capital punishment ever made past the censors of Franco’s Spain.

By 1963, Berlanga had already perfected his sly delivery; Welcome Mr. Marshall! (1953) and The Rocket from Calabuch (1956) were bombastic sendups of Spanish provincialism and American ego wrapped in a romantic charm akin to Tati’s Jour de fête. Meanwhile, That Happy Couple (1953), Boyfriend in Sight (1954), and Placido (1961) gorgeously tackle relationships and family through the searing lens of class. Together with fantastic collaborators like fellow director Juan Antonio Bardem (Death of a Cyclist, Calle Mayor) and screenwriter Rafael Azcona (Mafioso, Peppermint Frappe), whose respective projects are classics in their own right, Berlanga built a cinema unlike any other; the wit of Lubitsch, the elegance of Renoir, De Sica’s bleeding heart, a Bunelian deviousness — all these reference points can map a vague idea of his work, but can’t pin down his idiosyncratic power. So it’s at this established point that together with writing partner Azcona, Berlanga delivered The Executioner, a spectacular balancing act, weaving wry farce around a barbed premise: the ease with which the state can turn someone into a killer.

We are introduced to José Luis (Nino Manfredi) as he delivers a casket to the prison where an execution is about to take place. He arrives here as an undertaker, and ferrying the dead away is a stark reminder that however indirect his role, José Luis begins the film as a complicit actor in the very system that repulses him. There is a gorgeous irony in the fact that his brother and sister-law, with whom he shares a cramped basement apartment, have a similar revulsion to him being an undertaker as he does to the executioner. Despite the proximity of their trade — working so closely they might as well be colleagues — the line between the one complicit in murder and the one who commits murder remains stark. This thin line is beautifully laid out in the influential Italian gangster comedy from just the year prior, Mafioso (1962), directed by Alberto Lattuada but written by the very same Rafael Azcona, which tells the story of a factory worker whose trip to his Sicilian homeland pulls him into the violent world he left behind. Despite their ostensible differences, the two films share a profound architecture tracing how fundamentally decent protagonists are shuffled toward violence by the fascistic forces of tradition and honor.

If these themes manifest themselves as mob loyalty and coercion in Mafioso, they appear in subtler ways here. José Luis’ path to becoming a murderer is via a litany of little accidents and missteps from his initial meeting with the retiring executioner Amadeo (Pepe Isbert), a forgotten bag, a charming daughter, an unexpected pregnancy, a quick wedding, an available apartment — one thing flows into another so naturally that it’s hard to find the crossed line until it’s far too late. “Mr. Amadeo, I’m a good man. My intentions are good,” José Luis proclaims after being caught in bed with the executioner’s daughter Carmen, and it’s this juvenile drive to prove himself virtuous that propels him toward his inevitable destruction. Before we know it, José Luis is at the government office being registered as an executioner, except the allegorical father/Franco stand-in Amadeo is handling all the paperwork; José Luis, on the other hand, stands off to the side gripping a melting ice cream cone like a petrified child watching adults talk. Later in the film, once the apartment is secured, the patriarch Amadeo lounges in his room watching as the next generation inherits the burden of his trade, the lovers unable to find a moment alone without a reminder of the hideous commitment José Luis has made, just as a telegram arrives announcing an upcoming execution.

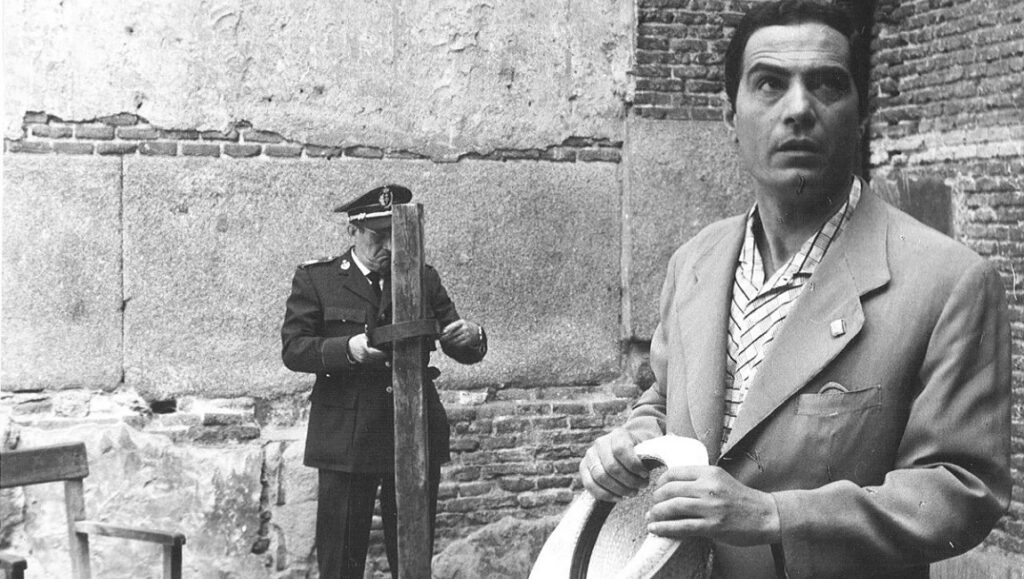

The bumbling banality of fascism depicted in The Executioner — much like Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains — makes the subsequent heartbreak all the more palpable. After all, Amadeo is a laughable little man whose power and influence are drawn through an inert bureaucracy puffed up by conservative values like honor, family, and tradition. This brand of fascism infantilizes José Luis as he scurries along, forsaking his dreams of becoming a mechanic, not to execute righteous “justice” as Amadeo defines it, but rather to do “right” by his family, ironically dooming his son to the same fate. Berlanga weaves through this tragedy a delicately juggled tone that keeps things just light enough that the jokes consistently land, while never quite losing grip of the stakes behind them. Never is this clearer than in the film’s spectacular closing act set in the picturesque resort town of Palma. As José Luis inches closer and closer to the dreaded execution, Carmen, the child, and Amadeo enjoy the vacation sights, sea, and sand. When the moment finally comes and the terrified José Luis arrives at the jail to perform his duties, it looks like he’ll finally back out. A tragically hilarious monologue breathlessly delivered by Manfredi recounts the sequence of events to a bemused warden who pushes him toward the film’s startling penultimate shot: both the executioner and the condemned are dragged across an empty prison yard, one behind the other, to meet their respective fates. Though still underseen, Berlanga’s marvelous film stands alongside the likes of Ōshima’s Death by Hanging as one of the greatest on the subject, and its acute portrayal of complicity in the face of fascist creep feels devastatingly current today. One can’t help but think of José Luis’ ridiculous straw hat, the one he bandied around all vacation, a symbol of the easy life afforded by his devil’s bargain, falling as he’s dragged kicking and screaming off-screen, discarded in the prison yard dirt.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.