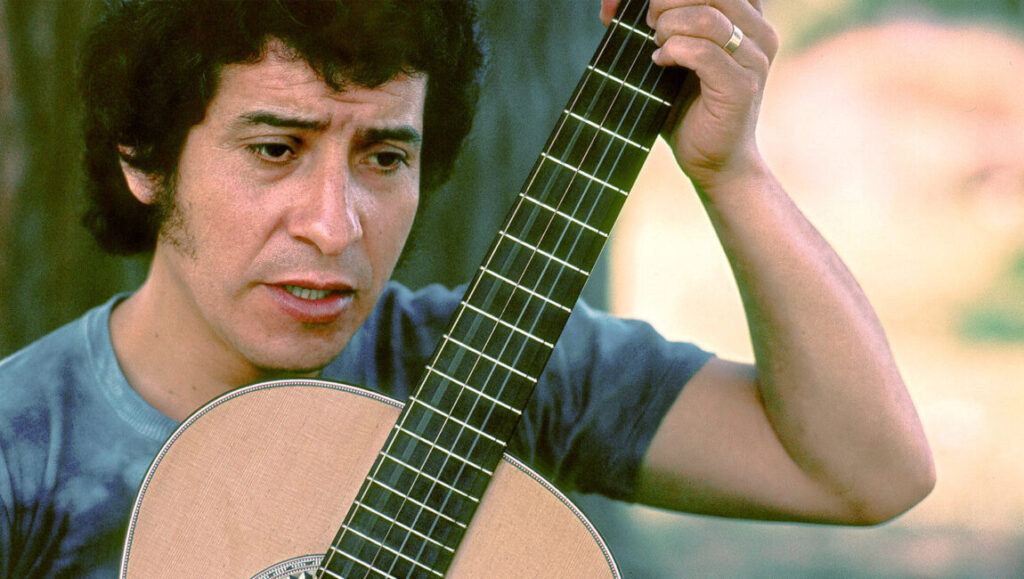

In her biography on her late husband — renowned Chilean singer/guitarist Victor Jara— Joan Jara recalls the days leading up to the impending sea-change in Chile’s political landscape, in the early 70s. The Popular Unity party, a left-wing alliance behind Chile’s then-socialist president Salvador Allende, was in the midst of a cultural struggle against reactionaries who sought to recapitulate popular song traditions to instigate fascist rule in the country. “For the first time, during this campaign,” Joan writes, “the opposition used pamphlet songs in an organized way, in an attempt to counteract the influence of the New Chilean Song Movement. It was a sign that they recognized the political power of song.” The opposition would reinvent popular rhythms and ready-made cumbias. Even Jara’s most recognizable tunes, like ‘El hombre es un creador,” were propagandized. Jara’s body of work, like his activism, bloomed in those years, forming a document that cut backwards into folk traditions and forward into intentional and active solidarity with Chilean workers and peasants. And even now, almost a year after nine retired Chilean military officers were sentenced for the murder of the singer in a massacre at a stadium — orchestrated during a coup by August Pinochet — one can still feel this level of unity brimming on Jara’s fourth studio album, Pongo en Tus Manos Abiertas…

Jara’s signature, syrupy delivery wended through South American folkways, and he joined a multitude of voices to channel the “political power of songs” in an attempt to reconvene the history of popular movements against the backdrop of imperial assaults on the global South.

The album was released on DICAP (Discoteca de Canto Popular; or, Popular Song Records) at a time when the United States and Europe had set out to conduct economic and political experiments in South America. Jara’s signature, syrupy delivery wended through South American folkways, and he joined a multitude of voices to channel the “political power of songs” in an attempt to reconvene the history of popular movements against the backdrop of imperial assaults on the global South. This much is revealed in the album’s outset. On “A Luis Emilio Recabarren,” a Peruvian flute joins dampened, soft and exquisite chords, finger-picked in gratitude to the Chilean communist Luis Emilio Recabarren. “I put in your open hands, my singing guitar / Hammer of the miners, Plow of the farmers…Simply, I thank you for your light.” Jara almost sobs on this first track, with an inflection that stands in contrast to the more raucous, almost-mischievous moments on the record. “A Desalambrar,” originally by Daniel Viglietti, undulates between righteous address and joyous pantomime, as the irony and abuse of agricultural capitalism is laid out: “And if the hands are ours, it is our own profit that they give us.” “Duerme, duerme negrito” lullabies a black child to sleep while her mother is forced to work the fields and Emiliano Zapata is heard crying for land and freedom over mid-paced tango on “Juan sin Tierra.” “Preguntas por Puerto Montt” mourns the massacre of peasant squatters by a wealthy Chilean politician, and “Móvil” Oil Special” frolics amidst good old cumbia/cueca in recognition of revolutionary student movements. The album even includes the hit “Te Recuerdo Amanda,” which tells of the tragic romance of a factory worker. “Ya Parte el Galgo Terrible” channels Pablo Neruda; and Pete Seeger’s “If I Had a Hammer” gets a passionate reworking, in “El Martillo.” According to Joan Jara, her husband once spent a day visiting miners and singing with Phil Ochs and Jerry Rubin. This may be a testament to the troubadour’s resonant qualities; his songwriting would go on to inform folk-protest music more generally. However, what’s most striking about his work are its parallels to this form, as it evolved across continents, with its stunning humanism never lost in translation.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.