Wong Ping’s Fables 2

The first of two fables in Wong Ping’s Fables 2 is entitled “Cow the Super-Rich.” It’s an amusing anti-capitalist tale about a cow who was, early in his life, a “radical social activist.” He believed violence was necessary for meaningful societal change and, after killing a police officer, was sentenced to jail for twelve years. Upon his release, he starts a company manufacturing and selling jeans, and is convinced that, in his newfound wealth, he still has the same burning desire to make a difference that he did early in his life. It’s in his death, however, that he’s most useful; his meat, which “rivaled Japanese A5 Wagyu beef,” is loved by locals. In an unexpectedly delightful way, Wong Ping utilizes “eat the rich” literally to make clear the meaning and value of the phrase. The second fable is even more haphazard, featuring conjoined triplet rabbits and a cameo from the aforementioned cow. While this story doesn’t land with the same power as the first, it’s consistently funny in its narrative progression, use of sound effects, and visuals. Wong Ping’s idiosyncratic animation style is deeply memorable, overflowing with the garishness of flash games from yesteryear, yet avoidant of any retro fetishist tropes of internet-loving visual artists. There’s a crudeness to the images and sounds that allow the innate silliness of these stories to truly shine. This, in turn, makes the seriousness of their messaging all the more impactful. [Part of Program 1]

Exam

Sonia K. Hadad’s Exam begins with a shot of a teenage girl (Sadaf Asgari) studying for a test. There’s food on the table, but she ignores it to spend time writing in her notebook and to repeat facts out loud. Her father scurries into the room to explain that she needs to deliver a package today, much to her chagrin. What that package ends up being, however, is an eighth of cocaine, and when the prospective buyer never appears, she’s forced to keep it in her backpack and bring it with her to school. There’s a shot of her ambling in an alleyway as cars pass — she’s clearly worried about getting to school on time — and it functions as an effective contrast to the film’s primary scene, which finds the protagonist in a crowded all-girls classroom after the completion of the titular exam. An adult comes into the room to explain that a random bag check needs to take place, and the tension that immediately ramps up in these few minutes coincides with a loose commentary on the strict policies present within these students’ lives; they have phones and a curling iron taken away, and one girl is chided for having dyed her hair. In barely showing the actual school exam taking place, Hadad posits the other ways in which adults force stressful tests on students, and how exactly they can so unwittingly burden. But for as suspenseful as it often feels, Exam still reads more like an individual sequence from a feature film than something self-contained, and its overall simplicity makes the underlying message feel incomplete. [Part of Program 1]

Monster God

Agustina San Martín has stated that Monster God is a film in which God is a power plant. Such an abstract concept lends itself nicely to an equally abstract film, one that begins with still shots of electrical structures amidst fog, the shots smeared in blues and greys. We hear the indistinct sound of a group prayer before a siren is then heard, making evident this structure’s holiness. Cows are seen grazing in a field, shot with a Reygadas-like patient mystique, and we’re soon bombarded with shots of children, the main figure of which is a girl wearing a spiked choker. “Last night I dreamed that I was electrocuted,” says a young boy who accompanies her, revealing San Martín’s desire to show the terrifying rule of God over creation. It doesn’t quite feel as sinister or bleak as it lets on, though. One scene shows people dancing to a song that repeatedly says “Jesucristo,” and it feels too obvious to add any depth to the film’s premise. The same is true for when shots of the powerplant appear once again, as a red light near the top of these structures is meant to suggest something living and all-seeing. The only thing that proves slightly unsettling, then: shots of cows staring directly at the camera. [Part of Program 1]

The Eyes of Summer

Rajee Samarasinghe provides background information for The Eyes of Summer before any image is shown. We learn that the film was shot in his mother’s village in Southern Sri Lanka in 2010, shortly after the civil war. It was also done collaboratively with family members and “improvised around an investigation into [his] mother’s interactions with spirits.” This all establishes clear expectations for the film, one whose tone is meant to be serious and contemplative — the greyscale images and lack of dialogue further point to this. It doesn’t quite ever feel that way, though, as the pacing is quick and its attempts at post-war emptiness are attempted via cheap images: a girl holding up the bones of a fish, dogs having sex in the middle of an otherwise empty street, close-ups of people’s faces. The film is relatively quiet, too, but it rarely feels meaningful in its quietude. Attempts at conjuring some sense of the supernatural are done through avant-garde techniques, the most successful of which is an overlay of a bright, white light transposed on another image. Still, these moments are simply too schematic, and the shallowness of the naturalistic images makes for a poor foundation to build upon. [Part of Program 1]

Sun Dog

There’s a three-minute drone shot that kicks off Sun Dog, the debut short film from Dorian Jespers. We traverse the frozen landscape of Murmansk, a Russian port city, and the film’s purplish hues and organ soundtrack instill a sense of light melancholy and desolation. We stumble upon a locksmith named Fedor, who’s first seen pissing onto snow. After the title card appears, we spend time on foot, the camera gently moving down a road as the city’s lights cast a dreary yellow across the terrain. There is, in the very isolated nature of the locale, a sense of something enigmatic about every person and place. Jespers’ hand-held camera and use of tilt-shift lenses build on this, creating an immersive yet queasy experience not dissimilar to Aleksei German’s work. And when we follow Fedor into a woman’s home, the set design and lighting make the interior space feel especially surreal. Near the film’s end, people start speaking to the camera directly, as if the viewer were along for the journey the whole time. The moment when this first happens is an unexpected but amusing surprise, and its effectiveness is a testament to Jespers’ larger ability to establish a tight, distinct atmosphere. [Part of Program 1]

Playback

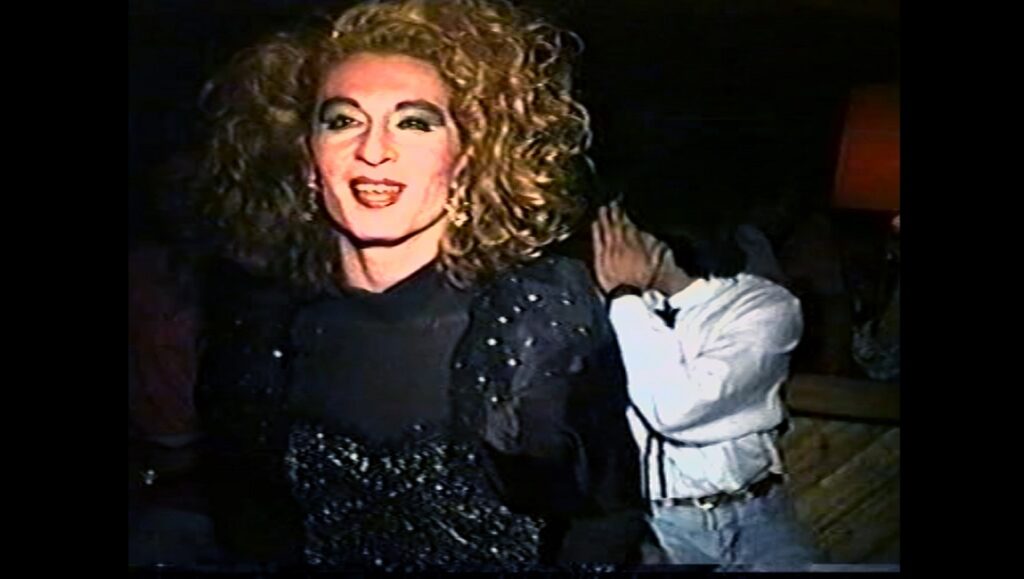

Agustina Comedi’s first documentary feature, Silence is a Falling Body, saw the Argentine director utilizing VHS footage and interviews to navigate the story of her late father’s life. He had, unbeknownst to her, been an activist and was involved in leftist and LGBTQ+ circles. It was through that experience that she learned of a partner he had earlier in life, La Delpi. She’s the sole survivor of Kalas, a group of drag queens and transgender women who convened in Córdoba during the 80s, a time in Argentina defined by Catholicism and military dictatorship. “All of those enchanted nights, those fantasy nights, those award-filled nights — we were very happy. Because if we didn’t give ourselves awards, who was going to do it?” she explains in Comedi’s new short film, Playback. That spirit of celebration and communal love is at the heart of the short, suffused throughout its many sadnesses. La Delpi narrates over archival footage, speaking of the AIDS epidemic that took the lives of friends, and of the films they created wherein friends who died were granted happier endings. She talks of a friend named La Colo, who died during the making of Playback. And parallel to what had been done decades prior, this film functions as a way for La Delpi to remember and honor the life of a beloved friend, one she considered a revolutionary. And in the VHS footage and playback performances, in the desire of these people to authentically express themselves, in the willingness to imagine better lives, Comedi makes clear that everyone who was a part of Kalas could be considered a revolutionary, too. [Part of Program 2]

After Two Hours, Ten Minutes Had Passed

Steffen Goldkamp’s After Two Hours, Ten Minutes Had Passed has a title that hints at its conceit: we witness men inside Hahnöfersand, a juvenile detention center in Germany, and get a sense for the lethargy of existence in such a facility. The film begins with a close-up of a Coca-Cola bottle between someone’s legs, a man fiddling with the red plastic ring underneath its cap. As men are seen lounging in the space, Goldkamp ensures that we never get a clear look at anyone’s face: they’re obscured by baseball caps, hidden in the darkness, or facing away from the camera. Halfway through the film, a turtle is seen moving along a bathroom floor — too on-the-nose, surely — and the title card appears. Upon seeing it, there’s a sense that we’re meant to reflect on how long the preceding events have felt, but the shots haven’t been as slow-paced as they seem. And as After Two Hours progresses, the title card is understood as a tool for bifurcating the film’s two distinct halves, the latter of which shows men at work, toiling away. A Beethoven string quartet begins playing as a man is mopping a floor, and this genteel soundtrack makes obvious the misery of the situation. It’s bizarre to see Goldkamp so noncommittal, moving towards a more didactic approach, and indeed, it feels a lot like hand-holding: the turtle appears once again, we see images of arms outstretched between bars, and the sole close-up of a face is of someone outside the building. It’s a frustrating pivot and insulting to viewers that Goldkamp spends the back half of his film simply explaining the subtext that came before. [Part of Program 2]

Happy Valley

Sound has always played a crucial role in Simon Liu’s films: looped or fractured audio clips match frenetic editing, the gauzy haze of his music mirrors his neon-drunk colors, and everything from pop songs to field recordings to silence bolsters the underlying messaging of his images. Music plays an especially crucial role in Happy Valley, a film highlighting the cloud of uncertainty that looms over the city of Hong Kong. The film begins with a chair-swing ride at a carnival, the blue-tinted image quickly contrasted by the sight of multiple fires. From there, it’s a constant barrage of images and sounds: shopping centers and Chinese ballads, a fish tank and electroacoustic hiss, ambulances and a warped version of “What the World Needs Now Is Love.” Liu’s sound and visual collaging create a tapestry of the manic and resplendent, and how they’re ubiquitous no matter where you look. The film veers away from the human in its finale, with images of a wire bridge soundtracked by uplifting brass and ambience. As we view the structure and its metal cords, there’s a sense of firmness, an upward trajectory approaching an infinity. The moods that preceded this moment — the claustrophobia of tight spaces, the dizziness of quick camera movements, the boredom and disorientation of the everyday — conclude with a moment of release and hope. Liu understands that such sentimentality can be grounded in reality without forsaking its encouraging power. [Part of Program 2]

Black Sun

It takes some time before the plot of Arda Çiltepe’s Black Sun reveals itself. The film follows an unnamed man (Enes Yurdaün) as he travels to the place of his father’s funeral, and with few words spoken throughout these 20 minutes, Çiltepe allows the sound of various environs to speak to the necessity of quietude in such times. There’s the buzz of a drill, the whooshing of wind, the lapping of waves: noises that are just enough to distract oneself from the rest of the world. In numerous scenes, the man is seen traveling — on a plane, in a car, by foot — and taking his time to arrive at his destination. Along the way, he makes stops at various locations — a beach, a hotel, a bathhouse — and there’s an array of emotions quietly underpinning this constant starting-and-stopping: an inability to find pleasure in the everyday, numbness from a loved one’s death, and a desire to avoid such an unwelcome reality. It’s stated that an eclipse is taking place and that animals have retreated from the area because of it, forcing us to consider the parallels between this rare event and the protagonist’s own excursion. The film ends without a concrete understanding of what’s to come: after the eclipse is over, after the man travels back to his home, will things be normal again? [Part of Program 2]

T

“We are here to honor our dead, we’re here to mourn, we are here to scream, to cry, to dance, to celebrate.” These are the first words spoken in Keisha Rae Witherspoon’s T, and they’re narrated over wistful strings and images of Black people dancing. We learn of Miami’s T Ball, an annual event commemorating the dead through lavish outfits and R.I.P. t-shirts. While we’re introduced to three characters who speak of someone who’s gone, T is ultimately a fictional film presented as documentary. And in opting for this format, Witherspoon points to the inability of an onlooker — an outsider — to ever fully empathize with those telling such stories. It’s made clear: there are inevitable limitations to understanding what the dead could have meant to those who loved them. At one point, a woman named Dimples enters a room to find her son, who we previously learned had passed away. He’s sitting there motionless, sunglasses on. “I know he’s not here, I’m not crazy” she says matter-of-factly. But then she starts to verbalize her pain: “You can’t fill up the hole in your heart — the hole in your heart can never fill up!” It brings to mind a mantra she imparted earlier in the film: “You create or you die.” And that’s what this fictional T Ball, these R.I.P. shirts, what even remembering is all about: They’re acts to keep the dead alive, which only helps the living to do the same. [Part of Program 2]

Comments are closed.