Promising Young Woman does its best to reshape the rape-revenge narrative into a novel form, but it ultimately fails to muster much ambiguity or thorniness.

Heavy with all sorts of baggage though it may be, the exploitation subcategory known as rape-revenge is a little-loved, oft-misunderstood zone at the intersection of cheap thrills, misogyny, sexual politics, and (occasionally) great art. From 1972’s grimy Last House on the Left all the way up to this year’s quite sensitive TIFF sensation Violation, there’s room for all manner of takes here, even if the results remain very often controversial. Emerald Fennell’s foray into this discourse, Promising Young Woman, won’t be immune to that kind of fallout even though it hits its targets as frequently as it misses them.

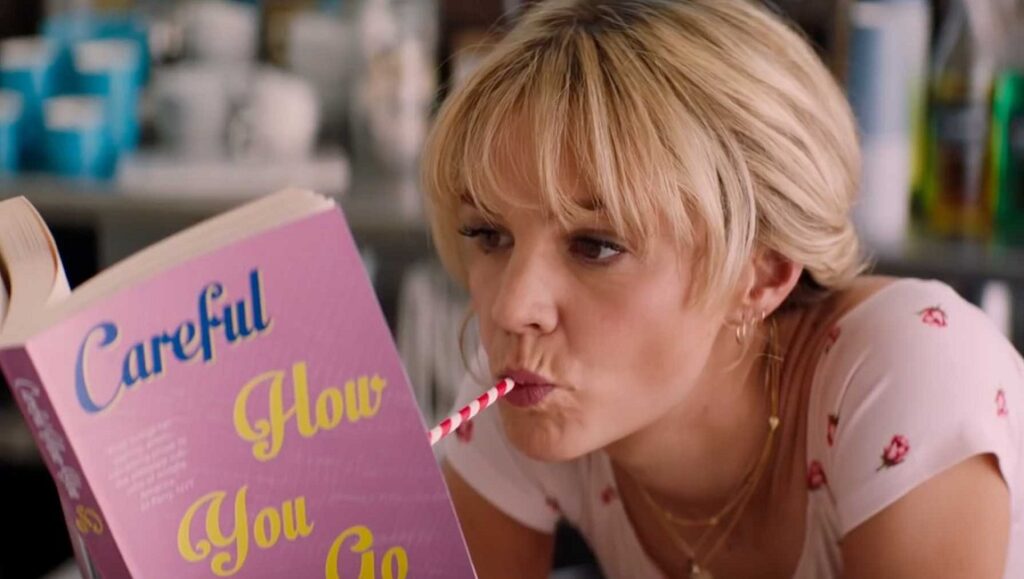

Carey Mulligan is Cassandra (maybe named for the doomed seer of Greek myth?), who, on her nights off from her barista job at a cute local café, gets dolled up, hits the bars, and pretends to be falling down drunk in order to attract horny and, shall we say, unscrupulous men who are only too willing to try to take an inebriated woman home for some adventures in non-consent. After she pulls the rug out from under them and offers a stern, cautionary lecture and some unpleasant threats, she’s on her way after having taught these assholes a valuable lesson. All the while, Cassie is reeling from the depression and trauma apparently caused by her best friend Nina’s sexual assault and eventual suicide in college, an incident that was resolutely ignored by not only the school authorities and law enforcement, but even by a few of her peers.

Mulligan is fantastic in the role, effortlessly communicating both her fierce anger and deep, deep misery. Each small tempest plays out across her face, and everything from catcall micro-aggressions to some dickhead’s David Foster Wallace recommendation are reflected back right back at their source. She’s even good at acting drunk. And when all this coincides with the reappearance of Ryan (Bo Burnham), an old acquaintance from her college days who presents as a shy but sweet dude with a lingering crush, her mask crumbles a bit, the resolve weakens, and we see the sensitivity that makes her trauma that much worse to bear. Meanwhile, Cassie graduates from shaming standard-issue creeps to more elaborate punishments. She allows Madison, a former classmate who brushed Nina’s rape aside, to believe she got drunk and was herself assaulted. She tricks the school administrator who ignored the crime into thinking her teen daughter is going to be assaulted by a group of boys. Indeed, her worst acts of vengeance seem reserved for women.

Fennell shoots the whole thing with pink, candy pop imagery, a sort of visual attempt at a razor blade in a cupcake, and it’s executed in a way that feels intentionally but also amateurishly edgy. It’s energetic but stylistically superficial, and the elements of grief and trauma on display seem pretty formulaic in this age of would-be woke genre films; up until its last half-hour or so, Promising Young Woman seems frustratingly safe. It’d be cruel to spoil things in detail, but it turns out that Cassie —dubious though her karmic punishments may be — has been embarking on an attempt at suicide-by-proxy this whole time (or at least aware of its potential), and the result is a harrowing final act that also backfires thematically. It’s clear that Fennell wants us to view this as a fuck you to rape culture and shitty men and the people in power who allow this culture to continue, and it’s likewise clear that we’re meant to be ambivalent about Cassie’s methods, especially given the outcome. Provocation is clearly the goal, and on that point, the film succeeds. But it’s hard to read the conclusion as any kind of meaningful blow against patriarchal power — the cops even get to play hero to a degree — and not merely another misery.

It’s a problem that this chilling coup de grace — the only section of the movie that’s really firing away and feels truly dangerous — is built on a shaky foundation of cheap douchebro stereotypes, retread girl-power revenge tropes, and cheeky formal gimmicks. It’s possible, maybe even likely, that the project’s strategy here is to lull an audience into a sense of complacency before a shocking rug pull, but that can’t really work because we learn materially very little about Cassie outside of her undeniable grief. Other recent attempts at this subgenre, like Coralie Fargeat’s grand-guignol Revenge or Isabella Eklof’s searing, austere Holiday, go to much greater lengths to damage the viewer by simultaneously repulsing us and making us empathize with cruel acts, but Promising Young Woman’s ambiguities seem trite and too easily palatable. This isn’t an incoherent film; its message is clear and righteous. But the problem is that it never succeeds at being intentionally thorny, which, given the material, is a requisite.

Comments are closed.