The Girl and the Spider

Like their previous collaboration, 2013’s The Strange Little Cat, Ramon and Silvan Zürcher’s The Girl and the Spider is best approached as a Rube-Goldberg contraption of physical/emotional pressure build-ups and releases. But whereas that film was set almost entirely in a Berlin apartment over the course of a single day, the Zürchers’ sophomore feature deliberately extends this organization: Mainly tracking a young woman’s, Lisa (Liliane Amuat), move away from the flat she currently shares with her roommate Mara (Henriette Confurius), The Girl and the Spider unfolds across a pair of apartment complexes over two days and one night. A blue-eyed Berliner with an intense, inscrutable stare, Mara at one point point reminisces about a bike trip she and Lisa took together, hinting at a time when they were happily, and romantically, attached. But it’s perhaps not so hard to see why things took a turn for the worse. Indeed, as we observe Mara unhelpfully wander about Lisa’s new apartment on moving day, at specific points spilling hot coffee on a dog, deliberately vandalizing a counter-top, and toying with a utility knife, we might eventually conclude that she is, at the very least, somewhat disturbed. Then again, by the end of the film, we might reach the same conclusion about every other character in the movie as well.

For the most part, the film’s constant sense of aggression is welcome, and makes for a good amount of fun as we are introduced to a literal host of complications: Apart from Mara’s unresolved feelings for Lisa, we also observe Lisa’s barely disguised hostility towards her mother, her mother’s flirtations with a hired mover, the mover’s assistant’s attraction to Mara, his eventual hookup with Mara’s neighbor, that neighbor’s history with one of Mara and Lisa’s other roommates, and so on. And though these action-reaction symmetries become rather tedious by the film’s end, the Zürchers at least take care not to violate their highly-stylized framework and underlying artistic hypotheses, which consistently render human activity with the same opacity as the material world. (The touch of fairy-tale suggestion in the title — seen most clearly in the succubus-like neighbor who sleeps during the day and roams the night — is for this reason appropriate, giving the impression of an insular, oddball fantasy.) If The Girl and the Spider ultimately feels too much like a recapitulation of The Strange Little Cat, it remains, for a time, a welcome tonic, its symphony of sights and sounds creating the sense of a world on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but never quite collapsing entirely.

Writer: Lawrence Garcia

Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn

Radu Jude’s films are an acquired taste, his unconventional brand of humour droller than Wes Anderson, more off-kilter than Tati, yet less misanthropic than Lanthimos. Both Uppercase Print and I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians, two recent reckonings with Romanian complicity in tyrannical regimes, exemplify their director’s stylistic idiosyncrasies. Despite incorporating archival footage, re-enactments, and piercing irony into patchworks of meta-theatrical performance, they don’t have the overtness characteristic of modern American satire (think 2006’s outrageously provocative Borat and its borderline-didactic, DNC-sponsored sequel), which their outwardly garish presentations suggest. This applies even more so to his latest work. Leaving the historical subjects of communism and fascism in his other films for the present-day, it examines an enduring legacy of social and national conservatism and its troubling implications for sexual and personal freedom.

Subtitled as the “sketch of a popular film” and segmented into three chapters, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn reveals a proclivity for free-flowing intellection via its essayistic blend of documentary, fiction, and aphorism. Emi, a secondary-school teacher, incurs the wrath of outraged parents after her sex tape finds its way online against her wishes. Citing trauma and violation on behalf of their children, they clamor for an official parent-teacher meeting to demand her resignation. Jude’s triptych presentation saves its meat for last, content with nibbling on starters that illuminate what essentially amounts to a cross-section of urban Romanian society. Shot during lockdown, the film incorporates the COVID-19 pandemic via extended sequences of Emi walking on Bucharest’s streets in the day, running errands and attempting to mitigate her predicament before the moral jury that evening. Pedestrians in masks openly acknowledge the camera’s presence, and Jude, recalling Tati’s techniques of isolation, frames moments of semi-staged slapstick against the backdrop of buildings and billboards. A stranger scorns Emi’s inability to afford a car; another runs a passerby over with his.

Jude’s camera pans and swivels, exploring the city’s materialist structures and dialectical contrasts: façades of buildings old and new, quarters gentrified and ossified, a store displaying anime next to the benedictive-sounding My Jesus. The little absurdities of these cross-cultural exchanges inflate in the film’s second chapter, whose A-to-Z compendium of witticisms — ranging from bawdy and inane (“blowjobs”) to solemnly scathing (“have you heard about German psychoanalysis after the war?”) — deconstructs the stubbornly intergenerational consciousness of the post-Ceaușescu era, its citizens stuck between ingrained ethnocentrism and capitalist pragmatism. Somewhat disappointingly, Jude is most didactic during the film’s third act, where the comical title is watered down as a committee of inquiry reveals, apart from profound hypocrisy and institutionalised misogyny, the director’s hyperbolic, flagrant attempt to condense a populace’s entire demographic into dramatic archetypes. To his credit however, these archetypes subtly conflate and contradict internally, and Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, cognizant of its sketchbook designs, has equal ire reserved for the high-falutin theorists and liberals. After all, these guys have the worst luck banging.

Writer: Morris Yang

Drift Away

Drift Away’s opening is a three-tiered one; within not even the first five minutes, Xavier Beauvois simultaneously presents the relationship between local gendarme Laurent’s (Jérémie Renier) work and home life, while intercutting a bride and groom photo shoot morbidly interrupted by a suicide that will in no doubt be that day’s call. As if the intriguingly granular details that imply the ways in which police work encroaches on this man’s life were not enough — a gun kept in the closet, the station house literally sitting right next door — Beauvois include a gratuitous death from the jump. Also, before Laurent begins his brief walk to work, he briskly proposes to Marie (Marie-Julie Maille), his girlfriend of ten years, whom he also has a young daughter with, Poulette (Beauvois’ own daughter, Madeleine).

The film continues to operate along these routine points of contrast, bombarding Laurent with the tiresome work he weathers daily, before esconcing him within the atmosphere of love and care his family provides. The path the film takes to reach its climax, however, is an errant one, teasing numerous plotlines that could possibly deal the final blow to the put-together façade Renier so ably presents. The opening suicide, a case of insurance fraud, a discomfiting mention of child abuse: all of these take their visible toll, but it’s during an encounter with a young, beleaguered farmer, Julien (Geoffrey Sery), that Laurent performs his fatal blunder. Near the film’s halfway point, Julien threatens suicide with a shotgun, and in keeping with Drift Away’s heretofore established rhythm, the event appears to be yet just another issue Laurent has to deal with before moving onto the next. That is, before his attempt to debilitate Julien with a gunshot instead kills him. What follows is an ostensible descent into existential matters of responsibility and violence — which mostly consists of Renier striking pensive poses in otherwise unremarkable compositions — culminating in Laurent being ensnared in self-righteous wanderlust, abandoning everything to take to sea.

The film’s Normandy setting and flirtations with policier tropes suggest comparisons to the festival circuit’s premier chronicler of murders in French coastal towns, Bruno Dumont. Dumont may meet pushback for the vacillating spirituality and depravity that marks his films, but Beauvois presents the negative flipside of this with Drift Away. His existentialism is merely nominal, only evinced by a grossly manipulative twist that prioritizes drama over actual human feeling. Whatever effects Drift Away managed before that point are by and large dispelled by Laurent killing Julien, which plays less like a productive end in itself than a means to get to the next act.

Writer: Patrick Preziosi

A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces

At this late stage in the coronavirus pandemic, it’s no surprise that the first of presumably plentiful documentaries devoted to the topic have begun to arrive. These works largely adhere to the common conception of documentary filmmaking as objective, capturing moments and answering questions about how this series of calamities happened. While this can indeed result in incisive and interesting work, it is in no way the only means of engagement, especially with a topic as all-encompassing as COVID-19. To help fill that gap, there is Shengze Zhu’s A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces, which premieres in the Forum section of this year’s Berlin Film Festival. Her last film was the daring and compassionate Present.Perfect., which relied exclusively on footage from various Chinese livestreamers in order to capture new, developing forms of self-expression and connection for the marginalized, and with River Runs, she applies that same precision and rigor to an even more contemporary topic.

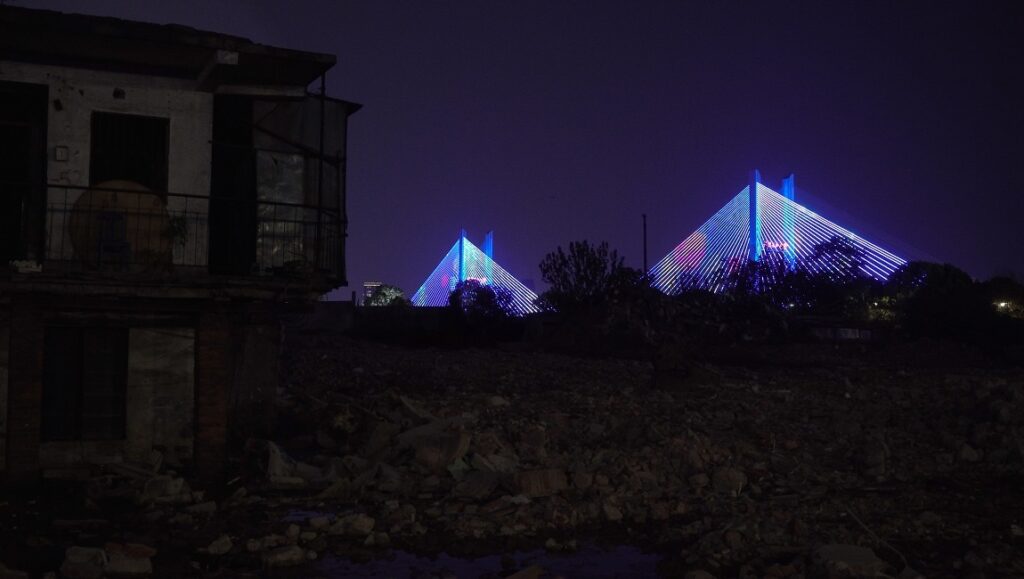

Zhu herself is from Wuhan, the Chinese city where coronavirus was first discovered, and where the entirety of River Runs was filmed, but any pretense towards exposé or journalistic explanation are quickly dispelled by the opening sequence, comprised of seven minutes of surveillance camera footage from February 8-April 4, 2020, showing the gradual progression from total lockdown to comparative bustle. This is as close as Zhu comes to showcasing a governmental response to the crisis, and indeed COVID-19 is never even mentioned by name in the film. Instead, the rest of River Runs consists solely of footage shot before the pandemic as part of a proposed installation project, proceeding in largely reverse chronological order from the fall of 2019 to the summer of 2016. Eschewing the dominant close-ups and constant patter of her previous film, Zhu only uses extreme long shots, which contain no dialogue whatsoever, filming numerous locales within Wuhan from afar. She focuses particularly on large-scale construction, towering bridges, and, above all, the Yangtze River, the banks of which flood near the end of the film. With a few exceptions, all of the locations are largely empty, with solitary figures dwarfed in the frame, largely the result of Zhu’s compositions (though social distancing inevitably springs to mind): in one scene, a soccer match can be heard just off screen, and the players and the ball occasionally intrude at the very bottom of the frame.

Into what might seem like an “objective” mix of cityscapes untethered from the present calamity, River Runs introduces a devastating device, presenting four letters written by Zhu and based on true stories from four grieving people, addressed to a husband, a grandmother, a father, and an older brother, respectively, all of whom died from coronavirus. These letters are presented silently, placing a line of handwritten Chinese characters on screen one at a time, each detailing the often-mundane sadness with which each person is contending, one that extends into such banal moments as chopping a chicken or swimming in the river. The third letter in particular is presented in a different manner, using typed-out characters, and provides such a clear motivation for the documentary’s images — the writer was unaware of her father’s affinity for the very bridges that form such a large bulk of the construction and backdrops here — that it seems quite possible that this might be Zhu’s own story. While this is not the case, it goes some way in detailing the ache of the film, the emotion that infuses the lonely, decaying buildings and desolate shores. Though none of this footage was initially intended as a commentary on the pandemic, River Runs creates an extraordinary poignancy both within and outside of this unexpected context. Zhu understands that, traumatic as it was, coronavirus merely intensified daily struggles, the loneliness and discomfort with which the vast majority of people have been living, and that quarantine mingled with and transformed their conceptions of places and people just out of reach in both space and time. By mapping those melancholy feelings and hazy memories onto the specifics of a city ever in flux, River Runs charts the present state of existence with stunning, heartbreaking clarity.

Writer: Ryan Swen

Copilot

A straightforward romantic drama that gradually reveals itself to be about something else entirely, Copilot is a modest success for about half of its runtime. Utilizing a mostly handheld camera and an uninflected approach to realism, Anne Zohra Berrached’s film follows the fits and starts of a young couple, Asli (Canan Kir) and Saeed (Roger Azar). She’s studying to be a doctor, he a dentist, and they bond over their mutual overbearing families and the weight of expectations thrust upon them. It’s fairly standard stuff — familiar but enlivened by fine performances, a keen sense of place, and a novel milieu. They’re both foreigners (she Turkish, him Lebanese) living in Germany, and the mix of languages — German, English, Turkish, Arabic — suggests the difficulty of communication in a rapidly globalized world. Copilot is broken into five chapters, one for each year of their relationship: year one is the ‘meet cute,’ year two finds them temporarily broken up, and so on. Things start to go south in year three and here the film deviates from charting a long term relationship to something approaching a thriller. Saeed becomes more aggressive and is spending more time at a local mosque, while refusing to introduce Asli to his new friends, taking furtive meetings in the street, and sneaking out at night to make secret phone calls. Concerned, Asli looks at his text messages while he sleeps, and something there shocks her. But Berrached plays coy and chooses not to spell out exactly what it is that Asli reads. Instead, Saeed tells Asli that she is responsible for keeping his secrets, whatever they are, and proceeds to disappear for the better part of a year. It becomes clear that he’s been radicalized and has helped carry out some sort of terrorist act, and the last section of the film is a steady narrative march towards the 9/11 attacks.

It’s a bold narrative zig zag, but Berrached fumbles it. Nearly two decades since 9/11, Copilot is clearly not a desperate bid for topicality, but it doesn’t do anything to add to our understanding of how jihadists are radicalized, nor does it succeed as a nuts and bolts procedural. It wants to both humanize these people and dramatize an epochal historical event, but winds up becoming an empty rhetorical gesture instead of a film. It’s a story that could have been better served by being a novel, where we might be privy to Asli’s inner thoughts. Instead, she comes across as passive and aloof, with no real reason to harbor a violent spouse other than the occasional declaration of love. Berrached seems to want to explore how complicit Asli is, or is not, in her seemingly willful refusal to deal with Saeed’s radicalism, but the film’s episodic nature and elision of granular detail ultimately leads to an vague, unedifying dead end.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Moon, 66 Questions

Moon, 66 Questions, the debut feature from Greek director Jacqueline Lentzou, opens with a series of grainy home video clips with dates from roughly 25 years ago imprinted in the top left corner. In voiceover, a young woman named Artemis (Sofia Kokkali) tells a stranger that she is returning home to care for her estranged father Paris (Lazaros Georgakopoulos), who is rendered nearly immobile by multiple sclerosis. Kokkali and Lentzou previously collaborated on the latter’s short film Hector Malot: The Last Day of the Year, which won the 2018 Cine Leica Discovery Award at Cannes, and their rapport is evident. Lentzou doesn’t stray far from Kokkali’s face as she learns the extent of her father’s illness and the full weight of her responsibility, which has been foisted on her by an absent mother and a bevy of self-absorbed extended relatives. Her few moments to herself are punctuated with seemingly involuntary outbursts of physicality — jerkily dancing in the garage, a heated game of ping-pong — as though waving a middle finger to her father’s own physical limitations, or daring her body to betray itself. In one heartbreaking scene, she acts out a still-raw childhood memory, playing both her father and a younger version of herself pleading to go on a school trip. She breaks down sobbing at the mere memory of her father’s cruel response, and we see how close to the surface these scars are, how grueling it must be to care for the person who has caused so much unresolved pain. Georgakopoulos, for his part, plays Paris with both hostility and helplessness. A former basketball player, clearly not used to asking for help, he now cannot even walk without assistance, and we see the toll it takes on his pride. Even as he relies on Artemis for almost every basic need, the gulf between father and daughter shows no sign of abating.

Amidst this charged environment, which takes place almost entirely in Paris’s large, well-appointed house in the countryside, hovers the duo’s extended family as they interview potential live-in nurses. Each meeting is an almost farcical tableaux of vanity and carelessness, with the family exhibiting more concern for gossipy neighbors than the health crisis at hand. There’s no reason this massive responsibility should lie so heavily on Artemis, yet there’s also little urgency in rectifying the situation — an indication of the family’s general carefree attitude, or Paris’s less-than-stellar standing among his siblings. Moon, 66 Questions is a self-described “film about flow, movement and love (and lack of them),” and its four parts are introduced through various tarot cards. True to her promise, Lentzou has crafted a film that channels the ebbs and tides of physical movement and emotional trauma, even eschewing a traditional score in order to let her two leads truly carry the weight of this family drama. And so, when a family secret is revealed (though not necessarily to the audience) Artemis and Paris are finally able to find a moment of communion that hints not so much at reconciliation, but — finally — recognition.

Writer: Selina Lee

Comments are closed.