IWOW is a work of pure hubris and self-aggrandizement, entirely devoid of the humanity that has informed Allah’s previous works.

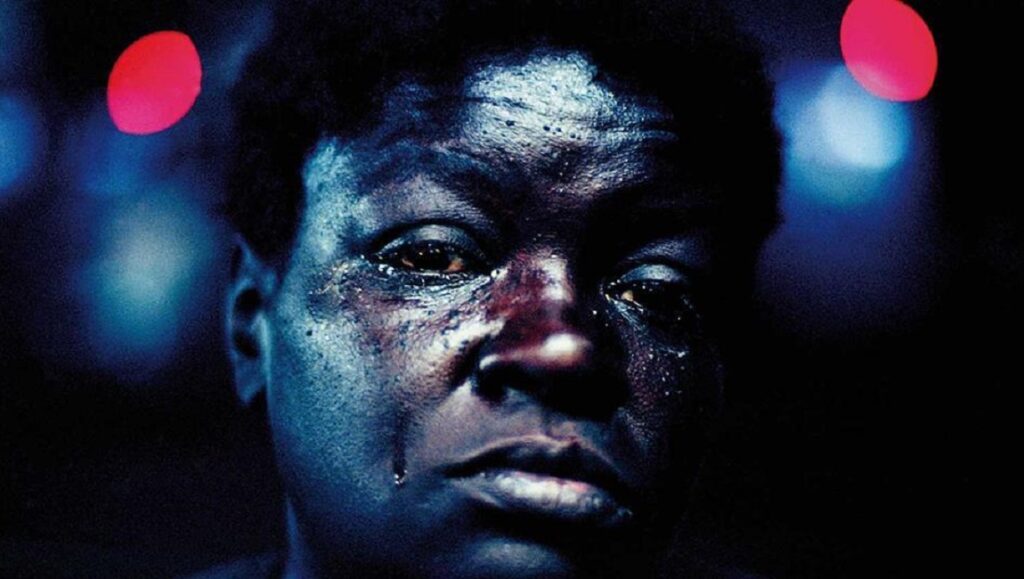

Over the course of his career, New York-based director Khalik Allah’s work has been suffused with an over-powering sense of the place he calls home and attention to capturing the faces and voices of its struggling and forgotten inhabitants. It’s a project best summed up by the title of his 2013 short film Antonyms of Beauty, and staggering for how his filmmaking has challenged, by means of paradox, what beauty even means when one has a camera at one’s disposal. Yet this project, which Allah has developed further with 2015’s Field Niggas and 2018’s Black Mother, and now including his latest Mubi-released work, IWOW: I Walk On Water, appears to have shifted into the realm of antinomy. The filmmaker-photographer’s now emblematic modes of asynchronous montage and non-diegetic voiceover become vehicles not for the views and ideas of those recorded to narrate and explicate their reality (something made all the more complicated, of course, on account of Allah’s position as artist, editor, and curator of such a thing), but here for the spoken psychology of the filmmaker to pass over his subjects in search of seeming validation of his own self-deification and catharsis regarding his own barely-confessed faults. The antonymic radiance found in the occupants of Harlem’s streets in past efforts encounters the ever-dormant contradiction that has persisted underneath this body of work: the filmmaker and his aestheticization of the bare life that surrounds him and on which he has made a career. It’s hard to not be turned off by the work, for as much as there seems to be the minimum amount of self-awareness (e.g. the voices of Allah’s mother, wife, and friends regularly question the filmmaker’s ideas — although they appear to function more as a chorus to be overcome than voices of correction), the director and self-professed god’s primary identification point and seeming defense is that of the bipolar-schizophrenic Frenchie, in whom Allah finds a broken reflection of himself and justifies his own divinity through the fulfillment of the unhoused and unwell person’s needs.

In a film full of ugly dynamics, it’s the one presented as obtaining between Frenchie and Allah that is most emblematic and concerning due to Allah’s dismissal of the unilateral relationship’s material dimension. The director argues that he has transcended such trivialities, encountering only the “essence” that underlies and connects both he and his subject — a line of reasoning which functions as barely veiled code for dismissing the question entirely. It’s this that perhaps allows one to understand almost no discernible humanity present from Allah’s perspective in any of the film’s voiceover conversations (even with those who are not beset by a serious mental disorder): in becoming a protagonist in his own work, the director’s photography and recordings are bent toward an abstract justification of his own theology and worldview, rather than engaging the concrete nature and position in the world of himself or those documented and recorded. IWOW is, then, a work of true hubris and overcome by the formal antinomy. Allah subjects it to contrasting images that draw out shudders of horror and empathy with recordings of himself that amount to deranged ramblings of a person who has lost ethical perspective while declaring himself a god. In contrast to Allah’s prior works, which highlighted the voices of the streets themselves or the director’s family and the milieu of their home island of Jamaica, his work here — subjecting the images of New York and its inhabitants to a shift in power relations — becomes repugnant. While the recordings of conversations between the mentally well suggest talk among equals that Allah allows to offer tame challenge, those that occur between the director and the occupants of the streets reveal a work Allah appears incapable of recognizing as appalling: a parasitic thing in which their beauty is extracted for the filmmaker’s glory, healing, and self-aggrandizement. And, indeed, in utter disregard of these criticisms — expressed too by his mother, girlfriend, and others throughout — Allah draws the film to a close in an epilogue and montage of streets, lips, and water as the sound of the director receiving fellatio ushers this work of self-deification to completion.

You can currently stream IWOW: I Walk on Water on Mubi.

Comments are closed.