James Benning’s The United States of America (2022) opens with a shot of Heron Bay, Alabama. With its muted landscape and dull blue sky, the space emanates an unmistakable sense of loss. Lining the horizon are the roofs of houses — one a dusty pewter, another a chestnut brown — and foregrounding the image are the dilapidated remains of a wooden structure. This doesn’t feel like the same country that defined The United States of America (1975), one of three shorts Benning made with Bette Gordon. In that film, the two mounted a camera in the back of their car to document a road trip from New York to Los Angeles, the windshield becoming a portal into the richness of America’s environs. With the two always in view, and with the vantage of a passenger, there was an intimacy and casualness to it, something aided by the constant use of dissolves. This spiritual sequel is more austere, working in a familiar structural mode that Benning has employed in the decades since. Each stationary wide shot lasts 105 seconds and is preceded by the name of the city and state being depicted. All 50 states are accounted for, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, but there is no continuity, no journey that lands in front of the Pacific. If there was a desire to capture the trek from “Sea to Shining Sea” back in 1975, then Benning aims for the particulars in that Johnny Cash song here; “the swamps of Okefenokee” and “Hibbing, Minnesota” are locales we indeed encounter in these 100 minutes. Now more than ever, Benning wants specificity.

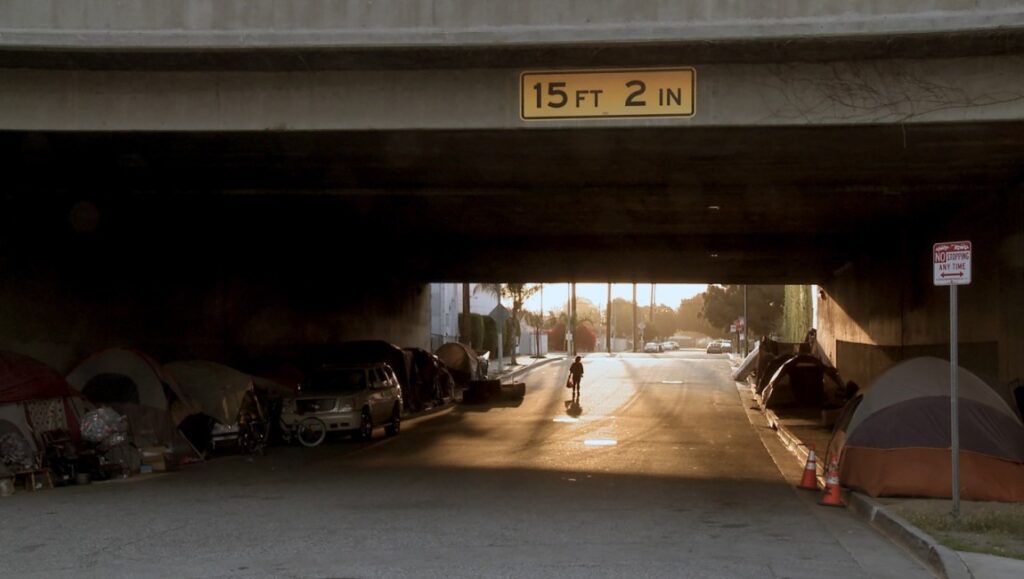

That specificity arrives in broad strokes: each city and town is lovingly captured, though the time we have to sit with each shot is relatively short. Being abruptly vacated from one state to the next is a pointed maneuver, however; one of the ideas presented here is that one can never truly soak in the entirety of the nation’s diverse environments, be they the barren lake in St. Elizabeth, Missouri or the snow-topped trees in Stemple Pass, Montana — one of the only shots animated by movement, the snowfall looking extraordinarily dazzling. This brevity is also, to hearken back to the 1975 film, in line with the transitory spirit of a road trip. Still, some images are striking enough as to be indelible: Little Eagle, South Dakota is almost hallucinatory with its slow-moving clouds, while Wilmington, California has this lovely golden sunshine tucked underneath an overpass. The United States of America (2022) is, at the very least, a feast for the senses.

Just as sound played a crucial role in the Benning and Gordon film, so too does it elevate this new one to something beyond pretty images. Back then, the two used the radio to channel the moods and ideas of the time: talk of the Vietnam War, a song from Deep Purple. Most notable was the repeated use of Minnie Riperton’s “Lovin’ You,” which appears only once here amid the clouds of Cleveland, Ohio. It’s low in the mix, however, and often hard to hear alongside nearby chatter. It feels odd, like talking with a former lover who’s all but a stranger now. In that aforementioned shot of Alabama, one hears the Carpenters’ “(They Long to Be) Close to You” below the ostensibly diegetic sound of the space. That track’s wistfulness is carried over to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” in Minier, Illinois and then to Riperton’s. Traveling from state to state, there’s a creeping understanding that any love one has for America ought to be checked for being misguided. The most subtly impactful song arrives in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. We hear Buena Vista Social Club’s “Dos Gardenias,” a track that may sound fitting on the surface. The Cuban group’s self-titled album was one of few instances where Latin American music found major success in the States. Its presence here is a reminder of Americans’ ignorant assumptions that all countries in the Caribbean or Latin America are the same. Even more, one recalls Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. commonwealth and America’s imperial pursuits of both Cuba and Puerto Rico; the former has generally been the more desired of the two, especially in its comparative depictions by media. America always wants what it can’t have.

There are more direct references to American horrors across The United States of America (2022). Benning chooses a cotton field for Fayette, Mississippi, and the audio we hear is from civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. He speaks firmly, “You have to build a movement so strong in this country that if one Black man is touched, every Black man will rise up and let them know they’re not gonna tolerate it.” An interviewer questions him with an incredulous tone, bringing up the supposed terror of “riots.” Carmichael swiftly corrects him, “I call them rebellions.” Later in Hanksville, Utah we hear someone discuss Manifest Destiny, the displacement of Indigenous people, and how they were confined to reservations. In both these moments, we remember that the wide expanse of America isn’t a freedom available to everyone.

Benning drives his point even further in the film’s conclusion. A parking lot in Milwaukee, Wisconsin is soundtracked by Alicia Keys’ cover of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” For a song so hackneyed and staid, Benning manages to draw poignance from its content. “Imagine there’s no countries,” we hear, reflecting upon the tragedies that characterize his own country. The song cuts out right after “imagine all the people” and right before “living life in peace.” When we land in the final state of Wyoming, the image of a barbed wire fence telegraphs the hatred, racism, and xenophobia that is the reality for many who live across America; peace is, irrefutably, not here.

In an astonishing finale, the end credits upset everything we think we have seen. There’s an impressiveness to the deceit he employs, and it’s a delight to see Benning deploy a longform gag, but most important is how it highlights the truth underlining the entire movie: The America many know and love is rarely one that’s depicted honestly. One thinks of Benning’s other film with America in the title, American Dreams (Lost and Found). The multiple narrative devices in that film complicate any neat image of the country, and one can see both United States of America films as their own separate strands of America to mentally superimpose. It becomes clear: In reusing the same title as his decades-old film, Benning forms a necessary dialectic between America’s scenic beauty and its sinister underbelly. “Lovin’ you, I can see your soul come shining through.”

Published as part of Berlin Film Festival 2022 — Dispatch 2.

Comments are closed.