The Code

If nothing else, Eugene Kotlyarenko is a filmmaker dedicated to understanding how we live with technology, and his greatest strength is a willingness to confront how uncinematic this can be and to push himself to invent something new. He takes the mundanity of staring at our phones as a challenge to experiment and innovate, and in his new film, The Code, this includes the use of over 70 cameras of varying quality and size, from iPhones to cheap consumer spycams purchased from AliExpress. Here, Kotlyarenko adds to the difficulty of capturing how we live now by also making this very explicitly a movie about the pandemic, a topic few are excited to revisit. Celine (Dasha Nekrasova) decides to turn her troubled relationship with Jay (Peter Vack) into a documentary, which is also on the surface going to be a movie about how couples navigated lockdown together. Celine and Jay haven’t been having sex, and they decide to go on a vacation to find the spark between them once again, while capturing every moment of it on camera. Jay, recently canceled due to a series of anonymous #MeToo accusations, gets paranoid about Celine only telling her side of the story, and so new hidden cameras are arranged, leading to a cacophony of prying eyes clearly intended to emphasize the lack of personal privacy under surveillance culture and the performativity of being a person on the Internet.

All of which is well and good, but Kotlyrenko luckily has the chops to make all this also genuinely funny, thank god. Much of the social commentary here is quite straightforward and expected, which could rankle if you’re hoping for the film to uncover something revelatory about our collective compulsion towards self-presentation. But the aim here appears more focused on lampooning all this for comedic effect and, more interestingly, using it as an excuse to play around with screenlife aesthetics and formal subjectivities. We bounce around between the couple’s seemingly endless portals into each other’s lives, often with multiple screens arranged for us — one marvels at the prospect of editing this film together into the coherent madness we take in — to dart around and identify what story we’re meant to be following. As a feat of filmmaking, it’s genuinely astonishing, which makes the spare moments that fall flat (extended riffs on cancel culture, references to Nekrasova’s real-life persona) easier to ignore.

Unlike Kotlyrenko’s previous film Spree (2020), which was similarly ambitious and sought to ape the hunt for online virality through the apathetic eyes of a rideshare driver, The Code is far better pitched as less a Black Mirror-esque treatise on the dangers of technological misuse and more an opportunity to reflect waggishly on the apparent breakdown of interpersonal communication and the Gone Girl-like potential of, just maybe, rekindling passion through the reality-blurring power of mutually assured documentation and representation, puked back up for consumption. In other words, it’s a film made by and for the irony-poisoned Extremely Online, but only as a jumping-off point for excavating real pathos from a medium (the cinema) that has been or has pretended to be threatened by all these screens. The Code, then, seems to prod and offer a specific provocation of the art form: try harder. Film has always been about voyeurism, its perversity and its pleasure, and the seeming inanity of what we see online and our natural inclination to spy over someone’s shoulder at whatever they’re looking at is taken to its logical conclusion here. One could crassly but accurately call it the rousing cinematic answer to digital brainrot. — JAKE PITRE

House of Sayuri

Horror and comedy share much in common. Both are affect-driven genres that hinge on build-up and release while helping us navigate through cultural taboos. For exemplars of this genre marriage, look no further than Wes Craven (the Scream quartet, The People Under the Stairs, and Shocker) or Tobe Hooper (Poltergeist and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2). However, effectively combining the two can prove challenging, and Kôji Shiraishi’s new film House of Sayuri is a case in point. Pitched explicitly as a horror-comedy, it hits some bumps in its merging of wacky humor with Takashi Shimizu-esque slow-burn Gothic.

The film begins with a multigenerational family moving from a cramped apartment into a spacious (but haunted) house, wherein a revenant spirit announces itself through increasingly menacing means — nocturnal whispers, possessions, and eventually murder. Shiraishi deftly handles the escalating supernatural intrusions. A specter flickering in guttering staircase light prefaces intense violence; one memorable scene depicts a dying character’s blood painting the wall red (a possible homage to Dario Argento’s Tenebre) before finally culminating in Junji Itô-esque surrealism, a ghost’s face unfurling into a mass of writhing tentacles.

Which is to say, Sayuri makes overtures to the cultural anxieties underlying many haunted house narratives, with several lines pointedly alluding to what constitutes a “happy life.” An early scene depicts a teacher asking her disinterested class to analyze a poem by posing questions such as “Where do we find happiness?” and “What exactly is happiness?” The film ultimately disavows the notion that domestic ownership equals anything like existential fulfillment or familial harmony. It locates horror in the conformist embrace of cultural repetitions, depicting its haunting as something like a tape stuck in a loop: the same ghostly giggle echoes through the house again and again, haunted TVs replay snippets of glitchy footage, and one character repeatedly watches the simulated reenactment of her beloved’s grisly death.

Shiraishi evinces a deep understanding of horror’s inner workings, which is no surprise, given that he’s responsible for the deeply upsetting Grotesque and the brilliantly dread-soaked Noroi, a masterclass in found footage horror. In Sayuri, he displays affection for the genre without relying on easy fanservice, and he also creates real stakes by refusing to pull his punches at crucial moments. He puts Sayuri’s clean-lined, open-concept haunted house to good use, using several cunning third-floor overhead shots to achieve scares.

Unfortunately, the film stumbles in its approach to comedy. Sayuri’s genre tensions are woven into its plot: the final act’s survivors combat undead evil by embracing their own “lifeforce,” using equal parts humor and tai chi to ward off wraiths. While horror and comedy share much in common, synthesizing the two within a single narrative can present complications: horror-comedy works best when it’s organically mining humor from its innate excesses. Put more plainly, the most blackly comic horror films know when to keep a straight face. Sayuri doesn’t locate that tricky tonal balance, so its fart gags, sophomoric jokes, and kooky mannerisms are realized as little more frustrating distractions.

At times, Sayuri does promise the kind of gonzo genre mix-up often mastered by Kiyoshi Kurosawa and Takashi Miike — consider, for example, the former’s Real and Before We Vanish and the latter’s Gozu and Lesson of the Evil. But while it never reaches anything near the heights of those films, it contains plenty of indelible images and moments, and sometimes that’s all a good horror movie needs. — MIKE THORN

Vulcanizadora

Joel Potrykus offered viewers a kind of hell on earth in 2014 when he released Buzzard, a crusty cumrag of a movie about the drudgery and paranoia of contemporary lower class life. It’s utterly brilliant, with a clear-eyed point of view that never looks down on its abjectly miserable protagonists — Marty Jackitansky (Joshua Burge), a temp worker at a mortgage company who pulls small-time, seemingly innocuous scams for extra money, and his friend Derek (Potrykus) — while also never shying away from sincerely investigating their desperate motivations. In many ways it’s a very funny film, and has a brilliant comic cadence in its story and characterizations. But a sad refrain accompanies its comedy… — CHRIS CASSINGHAM [Read the full previously published review.]

Electrophilia

In her 2019 memoir, In the Eye of the Wild, French anthropologist Nastassja Martin grapples with the aftermath of a near-fatal bear attack in the Siberian wilderness, an attack which left her mutilated and also threw her life out of balance in a more philosophical and spiritual sense. Her friend, Andrey, articulates her encounter and miraculous survival thusly: “He didn’t mean to kill you, he wanted to mark you. Now you are medka, she who lives between the worlds.” Medka is a word used by the Evens people to describe those who have been “marked by the bear” — survivors of bear attacks that are henceforth considered to be half human, half bear.

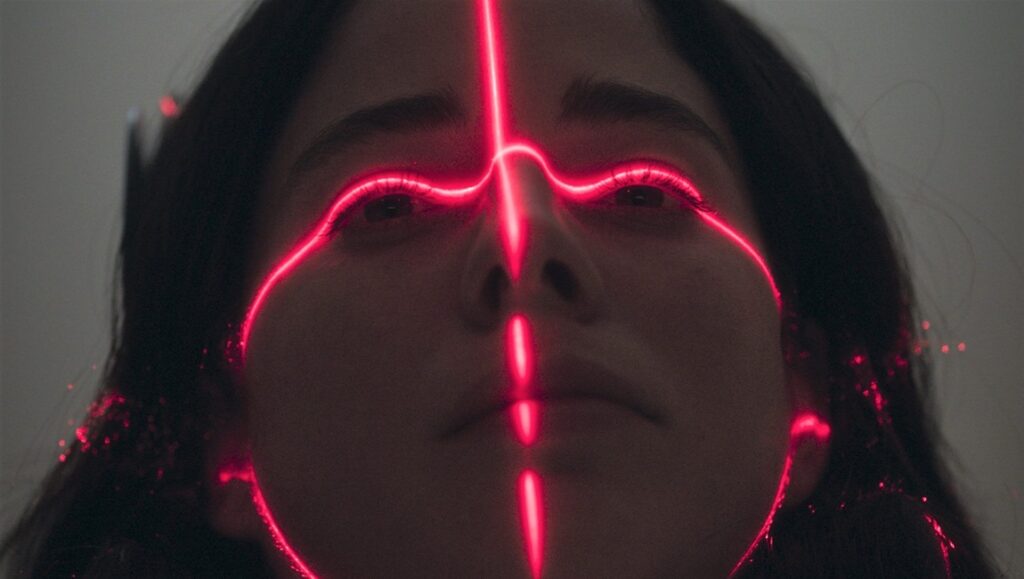

Like Martin, Ada (Mariana Di Girolamo), the main character in Lucía Puenzo’s Electrophilia, has a similar encounter with a terrifying, unknowable force of nature; one, however, that doesn’t come in animal form and on which something akin to reason can be mapped out even less: lightning. Waking up from an induced six-week coma, the young veterinarian finds herself a changed woman after a lightning strike nearly kills her. Understandably confused at first, she quickly notices changes of a more permanent nature. Not only is she more sensitive to light and sound, but she appears to have come down with a bad case of electromagnetic hypersensitivity, a condition very much rooted in the world of pseudoscience in the real world but treated as genuine by the film.

But the biggest changes come via Ada’s vivid auditory and visual hallucinations, an apparent ability to produce charges of electricity (though she cannot control them), and a noticeable decline in her mental stability. While this works to isolate her from the people in her life and makes a return to her previous routine difficult, Ada falls in with a group of lightning strike survivors who seek to reclaim their experience and embrace the various changes they have gone through after the fact. This group is led by Juan (Germán Palacios), an enigmatic doctor who seeks to understand the nature of the survivors’ condition.

There’s an obvious parallel in Electrophilia to David Cronenberg’s 1996 erotic drama Crash: character goes through traumatic event, event changes them in unexpected ways, character falls in with a group of people (led by a charismatic doctor) in a similar predicament (or in the case of Crash, with a similar predilection), and the allure of outer-limit experiences exerts an inexplicable and strangely, disturbingly sexual pull. Granted, with Puenzo, the sensuality is executed in a more muted manner, but the comparison is plain nonetheless. When Juan administers electroconvulsive therapy to Ada, she moans and writhes in both discomfort and pleasure, her face bright with a relief that resembles post-orgasmic bliss once the treatment concludes. The ensuing affair — Ada is already in a relationship with Jano (Guillermo Pfening) — between researcher and subject is pretty much a given at this point.

But this reflects a kind of duality that is unfortunately rare otherwise. There is no living “between the worlds” in Electrophilia, nor is there a sense of profound change to Ada aside from her emotional volatility and choice instances of sexual recklessness. Unlike the real-life Martin or Crash‘s fictitious cast of car crash junkies, Ada’s body is neither scarred by the savage claw marks of a wild animal nor the industrial, metallic force of an automobile that renders her a kind of human-animal or human-machine hybrid. (Even her more base appetites seem to be the stuff of a midlife crisis, rather than a life-altering brush with death.) Instead, her body is marked by the comparatively elegant and minimal patterns of a Lichtenberg figure, a relatively tasteful reminder of the ordeal she endured.

As indicated by this difference, Ada’s journey into “electrophilia” doesn’t take her to the outer edges of her consciousness, psychology, or humanity. Puenzo provides flashbacks that tether her film to subject matter that feels painfully familiar — complaining about what this familiarity is, one can’t help but feel like a broken record at this point: namely, childhood trauma. Her distrust of psychotropic drugs (suggested and administered by her doctor father, played by Osmar Núñez) ties back into memories she has of her mother, and this renders Ada’s feelings and motivations too legible while never taking the film outside the realm of its educated middle-class scope.

For all her trouble and for all the drama the film suggests, Ada’s ostensible exploration of the unknown drives her right back into the arms of a comfortable (and monogamous) existence. A little wiser (perhaps), therapized (certainly), and a little more aware of what lies beyond; but there is no sense of a cycle truly being broken, no moment that could be seen as a liberatory breakthrough — not even a desperate, if unsuccessful, grasp at it. At one point in her memoir, Martin writes that “all is permitted when you are rising from your own ashes.” Reading about the break-your-chest-open-and-let-your-guts-spill-out changes she went through again and again, her statement is heavy with meaning. One wishes Puenzo would’ve envisioned her main character’s arc in a similar way. — FRED BARRETT

Chainsaws Were Singing

2024 has shaped up to be a boon year for DIY cinema, with achievements like Hundreds of Beavers and The People’s Joker emerging as critical darlings and massive audience hits alike. Despite their minuscule budgets and relatively unknown performers, these films have been lauded for their formal ingenuity and innovative storytelling techniques, both significant contributing factors to their wild successes. Not one to be left out of the conversation, Estonian filmmaker Sander Maran enters the low-budget fray with his own feature, Chainsaws Were Singing. Self-proclaimed to be a mix of “Monty Python meets The Texas Chain Saw Massacre meets Les Misérables,” Chainsaws Were Singing is indeed a horror-comedy-musical, evoking the spirit of Peter Jackson’s earlier splattery efforts as it aims to make viewers laugh, cry, and feel sick to their stomachs. Well, two out of three ain’t bad, as Chainsaws Were Singing is largely enjoyable to watch, brimming with enthusiasm and endless buckets of fake gore to accomplish its mission. The feature ultimately runs too long for comfort, diluting its cleverness as it stretches past its baked-in expiry date, but for the first two-thirds of its runtime, the unhinged enthusiasm feels infectious.

Chainsaws Were Singing wastes no time getting to the carnage, opening with Maria (Laura Niils) being chased by Killer (Martin Ruus), a “fuckface with a chainsaw” who carves up a hapless bystander in the process. Meanwhile, they’re being tailed by Tom (Karl Ilves), a recently single and depressed young man who has met and fallen in love with Maria, vowing to save her from this menace. He’s accompanied by goofball Jaan (Janno Puusepp), offering his various motor vehicle skills for assistance. (In a hilarious running gag, every car seen in the film explodes if it so much as runs out of gas. “They go like hot cakes,” Jaan laments.) Killer eventually makes off with Maria, taking her back to his family of backwoods cannibals, led by the violent and domineering Mother (Rita Rätsepp) with the intention of adding Maria to the dinner menu. Divided up into chapters, Chainsaws Were Singing switches POVs between its lead characters, gifting each with extended musical numbers to tell their tales. For Tom and Maria, it’s a blossoming relationship, except Maran subverts romantic expectations by having Maria proudly profess in song her unconditional love for Tom’s body hair, weak knees, and beer breath. For Killer, the tale is of a misunderstood giant with a gentle soul, thrust into a vicious lifestyle by a sadistic matriarch, who even framed him for the murder of his own father. If that doesn’t make it clear, Chainsaws Were Singing has plenty of energy to spare, even emulating Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead animated camerawork at its best, zipping from one set piece to another. The press materials cite The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as an influence, but the film is really more akin to Tobe Hooper’s gonzo sequel, Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, eschewing any actual dread for deranged amusement.

Not everything lands as intended. At nearly two hours in length, Chainsaws Were Singing runs out of gas long before it reaches the finish line — films of this ilk tend to play better when they clock in around the 90-minute mark, clocking out before they become too exhausting. This longer runtime allows Maran to indulge in plenty of narrative digressions, the lamest being an encounter with a group of forest dwellers dubbed the “Great Bukkake Tribe” who seek enlightenment from a fridge-dwelling entity that spews copious amounts of ejaculate. Sure, it results in the obvious gross-out gag you’d expect, but it also stops the film dead in its tracks to execute the punchline. And so, at the end of the day, Chainsaws Were Singing feels tailor-made to be a hit with midnight screening audiences, who are sure to celebrate its serial irreverence and exaggerated violence. No worries, though: to gauge whether you might be a member of this most amenable audience, Chainsaws Were Singing offers the perfect litmus test with a sequence that showcases Killer’s brute force as inflected on a trio of disgruntled motorists: one poor bastard forcibly has his eyes gouged out, then proceeds to get his testicles ripped off and subsequently shoved into his newly emptied eye sockets, causing him to exclaim “Ow, my eye balls!” while predictably writhing in a great deal of pain. If that sounds like your particular idea of a good horror film time, run, don’t walk, to Chainsaws Were Singing. — JAKE TROPILA

100 Yards

Xu Haofeng makes movies for people who enjoy and understand the finer points of martial arts choreography. His best-known film work (he’s also a novelist) is probably the screenplay for Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, in which Wing Chun master Ip Man navigates the various schools and styles of early 20th-century kung fu. Two of Xu’s earlier directorial efforts, The Sword Identity (2011) and Judge Archer (2012), have a strong cult following, although this writer hasn’t seen them. On the other hand, Xu’s The Final Master, which received a proper US release back in 2016, is a dour slog: the choreography is indeed unique, realistically fast and detailed, but the story of rival martial arts schools in pre-war Tianjin lacks dramatic sense… —SEAN GILMAN [Read the full previously published review.]

Carnage for Christmas

In what is somehow 19-year-old filmmaker Alice Maio Mackay’s fifth feature, Carnage for Christmas, genres abound. Though a slasher makes up the bones of the plot, the narrative is also framed by protagonist Lola’s work as a true crime podcaster, while Mackay additionally uses the Christmas setting both to augment the horror and to bring Lola back to her hometown, placing her in implicit conversation with the past. Carnage for Christmas begins with Lola addressing a listener question about the origins of her interest in true crime. She recounts first a local legend about a toymaker who killed his family and himself after dreaming his wife cheated on him, and follows that up with the story of her own discovery of the long-missing corpse of the murderer’s youngest daughter while engaging in a youth ritual of entering the haunted house.

Lola notes that the kids who dared each other to enter this house were “mostly boys,” and in some ways, the tale stands in for the transition origin story expected for trans narratives, both fictional and non-fictional. Her transness here is a static fact throughout Carnage for Christmas, and all tension surrounding this is brought about by forces external to Lola: it’s her sister’s TERF-y roommate or the gas station clerks giving her dirty looks who are anomalous in this world, not Lola. In fact, the preoccupation with transition that defines much of trans media is distinctly marginalized here — a welcome shift in representation. As it becomes less remarkable for a trans person to make a film, the same is able to become true of the trans characters they write.

Mackay’s welcome delicacy in this regard allows the film’s point of interest, then, to become its genre, which, for better or worse (mostly the former), it largely exists within rather than subverting. The podcast recording at the start of the film essentially functions in place of a flashback, and the director manages to overcome the potential visual blandness of two women talking into microphones for the first ten minutes of the film. It’s in this sequence where the voice of editor Vera Drew, director of The People’s Joker, is most felt, flitting from stylized footage of the kills Lola describes to animated sequences. The rest of this film is not so frenetic as Drew’s own 2024 release, settling instead into amiably straightforward slasher territory and deploying a familiar low-budget horror aesthetic for the rest of its respectably brief runtime. In this, Carnage for Christmas proves to be a suitably compelling watch, likely landing even better for viewers who are fully invested in its playful horror trappings (which this critic isn’t quite). But again, perhaps counterintuitively, that the film is well-executed but somewhat intentionally unremarkable is actually a genuine strength. Though Lola’s transness is ultimately a key point in the film’s plot and its contribution to the slasher, Mackay’s project is more defined by its genre than its queerness. In a climate where representation is too often taken to be its own end, it’s refreshing to see queer representation instead as a statement of fact within a larger vision. — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER

The Beast Within

Director Alexander J. Farrell’s The Beast Within opens with a quote about there “being two wolves inside each of us,” followed by a brief but bloody werewolf attack. In other words, he’s not being coy about what this particular movie is about, and it’s no spoiler to say that our protagonist, Noah (Kit Harington), is dealing with an acute case of lycanthropy. Which is why it’s all the more disappointing when the film inexplicably downplays any genre thrills for yet another slow-paced, somber mood piece about lost innocence or whatever. In other words, we are firmly in elevated horror territory, immersed in what writer Parul Sehgal refers to as ”‘the trauma plot.” Preexisting psychic damage is everywhere, and it defines everything.

Much of the film unfolds from the perspective of young Willow (Caoilinn Springall), who lives in a secluded compound with mother Imogen (Ashleigh Cummings), father Noah, and grandfather Waylon (James Cosmo). Imogen is a caring, attentive parent, but occasionally she and Noah disappear, and when they return Imogen must clean blood off of his clothes. Harington plays Noah as a coiled bundle of anger, turning his pretty boy good looks into something that feels much more dangerous. Farrell and co-writer Greer Taylor Ellison do manage to string some genuine tension out of their scenario, as Willow must gradually discover what we in the audience already know. There’s deep familial discord here, which we only get snippets of: Noah seems moody and erratic even when it’s not a full moon, and Cummings’ portrayal of Imogen suggests deeper traumas than just a monthly transformation. Willow also suffers from some ailment that requires her to drag around an oxygen tank at all times, adding additional stresses onto a family that already feels like it’s falling apart at the seams. The filmmakers try to mix things up, inserting a brief, recurring flashback that proves to be an unreliable memory of sorts, while also occasionally jumbling chronology for brief bursts of expressionistic introspection. But the crux of the film remains fairly banal — something is wrong with Dad, and everybody knows what it is except Willow.

Beyond that, there’s simply not much else to The Beast Within. Cinematographer Daniel Katz crafts some appealing images, in that slick, prestige TV kind of way, but otherwise, Farrell’s film looks like every other ponderous horror movie of recent vintage. There are no surprises to be found, nothing screenwriters haven’t endlessly excavated and viewers endlessly seen before. Mounting dread and tension work best when they build to something explosive, but The Beast Within offers genre fans a scant few minutes of terror only at its very denouement. A ludicrous little twist that ends the film suggests the filmmakers themselves felt a similar way, and decided to goose viewers at the last minute, but it’s too bad the stinger makes no real narrative or conceptual sense. The cast is at least uniformly good, and their commitment carries things as far as something like this can reasonably go. Curiously, if you excised the film’s brief prologue and the film’s final few minutes, you’d have a straightforward, reasonably powerful family melodrama. Which reminds us what a problem it is that this is supposed to be a horror movie. As Scout Tafoya wrote in his original 2019 piece about the rise of this pernicious subgenre, the problem is that you “squint and these films can become about anything.” — DANIEL GORMAN

The Killers

Between Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, the seemingly never-ending V/H/S franchise, and even Yorgos Lanthimos’ Kinds of Kindness, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year and is currently out in cinemas, anthology films are arguably having a moment. The appeal of such a project is understandable: why tell one single narrative when a director — or a series of directors — can offer a wide array of amuse-bouches, experimenting with form and storytelling conventions within the economy of a short, leaving viewers with a nice variety to enjoy. The options can certainly be enticing, but the drawback is always consistency: for every Memories, there are at least half a dozen Four Rooms… — JAKE TROPILA [Read the full previously published review.]

Comments are closed.