While the experimental “sidebar” screenings at larger film festivals receive more than their share of critical attention, they only have so many slots to program. While this perhaps promotes selectivity and careful curation, it also means that younger filmmakers and their promising but imperfect films are often overlooked. This is a limitation that is experienced both as a critic/viewer and as a programmer. One advantage that a festival like Light Matter has over these best-of showcases is that its breadth allows us to see a wide array of films from around the world and from makers at varying stages of their careers. As with festivals like Crossroads and Prismatic Ground, Light Matter provides a kind of core sample of the present moment in experimental production, and part of the benefit of Light Matter is that, alongside highly polished films by established artists, we are able to experience diamonds in the rough, films that may have their problems in terms of form or concept but offer a glimpse of new talent in the process of discovering itself.

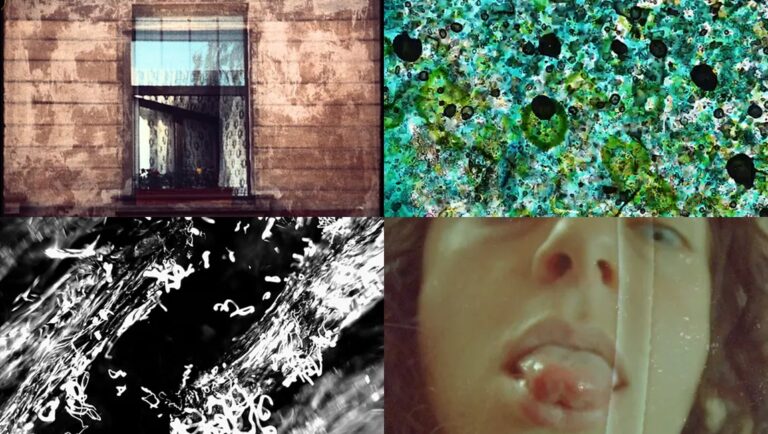

This piece will focus on two Light Matter programs: #4, “When Was I,” and #8, “Bajo de superficie.” Both programs feature over an hour’s worth of short films, a mix of work by newcomers and older, more established filmmakers. A few films, like Leonardo Pirondi’s Adrift Potentials and Mike Stoltz’s Holographic Will (both in Program #8), have screened widely at other festivals, and with good reason. Adrift Potentials examines the history of artistic and political resistance in Brazil, adopting an imaginary found-footage trope to consider the filmmaker’s cross-cultural aesthetic, while Holographic Will uses a rolling and turning camera to create a cyclotronic representation of a single domestic interior. But the most intriguing work in these programs came from filmmakers with whom this writer had previously been unfamiliar. Here are some images by Swiss filmmaker Yannick Mossiman is a complicated, even flawed film, but one that shows its maker to be on the right track, engaging not only in certain classic avant-garde strategies (found footage, direct light exposure, attention to the surface of the filmstrip) but taking a second-order approach to the material. Onscreen text poses questions and answers about what we are seeing, suggesting a hypothetical dialogue between the filmmaker and his audience. Are we really seeing an image, or are we asked to look directly at the film, treating its abstract colors and scratches as the filmic event? How do we make meaning from this abstraction? At times Here are some images can be overdirective, as though a purely materialist film requires rhetorical framing in order to connect with the spectator. But Mossiman is perhaps providing his own spin on the essay-film format so popular at the moment. Instead of explaining clear, realistic historical artifacts, it is formalism itself that is under consideration, the contradiction being that Mossiman asks us to simply use our eyes to see but also conceptualizes this process as a kind of argument.

Also working in physical abstraction, Masha Vlasova’s Midsummer takes up a well-known experimental method in order to question its basic premises. The film is a rayograph, with objects placed directly on top of light-sensitive paper which is then filmed on an optical printer. In a sea of blueprint blue, we observe natural forms floating by: leaves, twigs, flowers in bloom. Over its short runtime, Midsummer becomes increasingly cluttered with complex forms, some of which appear more photographically based than the initial rayographs. This prompts a slight confusion between figure and ground, such that we cannot tell what may have been photographically registered on the film in the first place.

Another film working in a classic idiom is The Year by Grace Mitchell. As the title suggests, Mitchell shot the footage over the course of one year, during which she takes us through a number of different categories of imagery. We see home movie material, Mitchell and her friends traveling or hanging out. We see nude self-portraits, along with a collection of bloody pads that allude to the body even in its absence. But the primary refrain in The Year is a shot down a suburban alleyway beside a house. Using the same exact camera setup, we see this spot in various light conditions, times of day, and over the course of four seasons. This shot resembles some of the California exteriors we often see in Laida Lertxundi’s films, but Mitchell incorporates them into a broad, abstract diary format. The disparate material is unified by the chronological movement of time, and the reference to the person behind the camera for whom these sights are concrete memories.

Mossiman, Vlasova, and Mitchell’s films are intimately connected to experimental film history, and they don’t entirely break free of their obvious influences. But they clearly indicate that these filmmakers understand the ways that structure and form can communicate with a viewer as directly as conventional narratives can. Content will evolve, but it’s much more important that these younger artists embrace the physical presence of film as the bedrock from which to build. One of the other notable films in Program #4 is Slideshow, the latest from an established veteran of avant-garde filmmaking, Janie Geiser. Geiser has been known as an experimental animator, someone who alters existing images and objects by using light, color, and sound to evoke anxiety or trepidation. With Slideshow, Geiser alters her working method, using actual slides in order to generate superimpositions and intersecting forms. Her earlier films usually entailed use of a copy stand and a stationary camera, but Slideshow has the feeling of so-called desktop filmmaking. We perceive Geiser at work, moving and organizing the images we see in front of us like an in-person demonstration. It’s a highly polished film that also conveys serendipity.

Program #8 also features works by younger filmmakers who demonstrate their facility with existing modes of experimental communication, putting their own unique spin on available styles and forms. Trace on My Body, by Chinese artist Yue Hua, looks a lot like a long-lost Nazlī Dinçel film, with its overworked celluloid surface and repetitive language scratched directly onto the filmstrip. This is a time-honored tradition of course, something Dinçel learned from Su Friedrich among others. For her part, Yue Hua offers a fragmented self-portrait in amber light, her body striped by the adjacent window blinds. With side-frame light exposures, ink and paint on the filmstrip, and a relentless skein of language obscuring the image, Trace on My Body takes sensual surfaces and infuses them with a sense of internalized anxiety. Likewise, Icelandic filmmaker Zoe Chronis’ Digital Light Leak resembles certain images in Peter Hutton’s Skagafjördur, also shot on the Icelandic tundra. Chronis shoots a waterfall in the distance, and at regular intervals the film is engulfed in flares and then total darkness. What may have been an accident — direct exposure of the film to available light — becomes the focal point of the work, the landscape appearing to breathe in and out of our vision.

Mexican-American environmental sound artist Abinadi Meza has focused his practice on filmmaking for the past few years, and his work in this medium seems to get stronger with each new completed film. His latest, Parangolé, is his best film to date. It is a hand-painted abstract animation composed for dots and splotches that expand and contract, generating a flattened perspective that also implies the existence of foreground and background. The film has antecedents, of course, above all the films of Normal McLaren and especially Basque artist José Antonio Sistiaga. Meza’s use of bright, saturated colors against the white field of the empty filmstrip also calls to mind the late Greenbergian canvases of Larry Poons and Sam Francis. What makes Parangolé unique is Meza’s use of rhythm, with marks moving around inside the image and the larger composition pulls in and out of the celluloid space.

Another film that is organized around the illusion of depth, Craig Scheihing’s to open a window, is probably the most accomplished work this writer saw in these two programs. Like The Year, to open a window appears to examine a handful of specific spaces across time. But closer investigation shows that Scheihing is most likely working with simple graphic matches to produce a dense array of ever-changing images. The film’s refrain focuses on a single window which rapidly changes color and light. It is in fact composed of multiple, same-sized windows, meaning that it’s not the actual space that remains stationary, but the shape itself. These passages alternate with fast-paced imagery from nature, such as light through spiderwebs or the leaves of trees. An unlikely combination of Nathaniel Dorsky and Rose Lowder, to open a window weds the sublime to the mundane, offering just what the title promises. The window, an utterly familiar form, is opened to new perceptual possibilities. Scheihing, like many of the other filmmakers discussed above, provides a glimpse of the new terrain that experimental film is likely to survey over the coming years. It’s a good thing Light Matter is on the beat, making sure we don’t miss anything.

Comments are closed.