Wonders in the Suburbans is an unwieldy affair, taking supposedly comedic pot-shots at any number of targets without any clear vision.

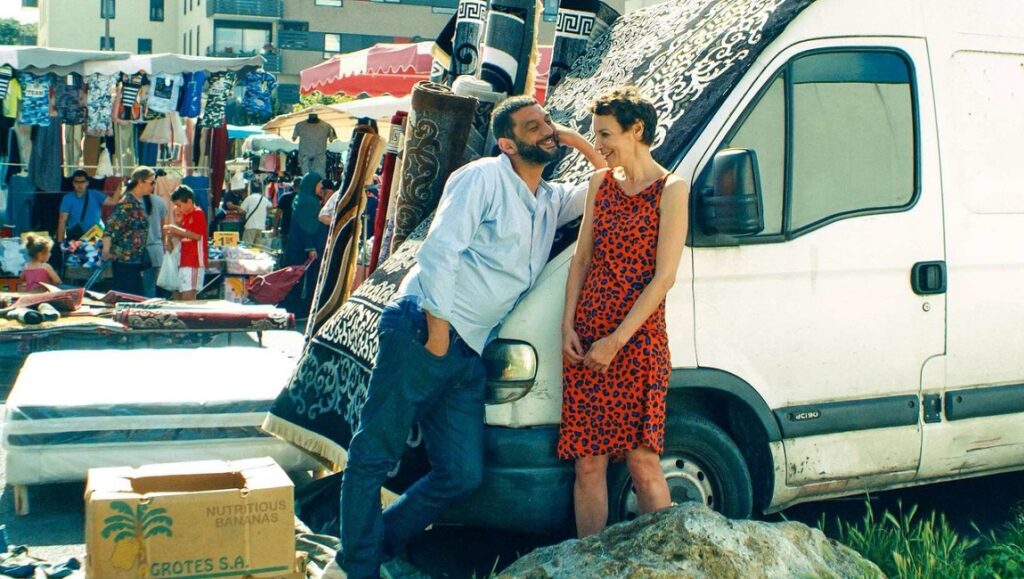

Jeanne Balibar’s brand of idiosyncrasy — most recently and prominently displayed in Mathieu Amalric’s Barbara — curdles with her solo directorial debut, Wonders in the Suburbs, a comedy of manners whose bureaucratically positioned perspective bungles any incisive observation or criticism of municipal governance, replacing that potential with clumsily deployed comedy that extrapolates an unwieldy class antagonism in a passive aggressive way. The film follows Joëlle (Balibar) and Kamel Mrabti (Ramzy Bedia), a married couple who both work for the town of Montfermeil’s new mayor, Emmanuelle Joly (Emmanuelle Béart), and who are also in the midst of (attempting) divorce. The focus often shifts, however, to a familiar cast of other faces — all of whom, in their peripheral roles, are in some way connected to the mayoral government. Each side character also proudly displays some distinctive form of quirkiness that seemingly keeps them from being particularly effective at their job; and yet, in what is as cogent a criticism as this film ever delivers, they all remain installed in their positions of power.

Evidently, this is a part of a more schematic kind of very-French slapstick, where a seemingly scathing humour (of the political class) is closely tied to the restless particulars of each character’s enunciation and use of language. Each beat in the narrative here is defined by a kind of discursiveness; there is no logic by which this film functions other than to supplant whatever might be one’s logical assumption about the way one of these characters would behave with some distant, absurdist version of that assumption. “Distant” because the manner in which this physical comedy is visually presented is both rigid and reliant not on any kind of character-centric physicality, but more often tied to mise-en-scene; jokes relate to the whole space rather than the individual in a way that makes the characters themselves seem small and insignificant — a feeling furthered by editing that abides by no sense of the kind of moment-to-moment continuity which could-have, should-have empowered the comedy here.

Eccentricity becomes the point of each interaction — with staggered speech, whimsical physicality, and garish spaces dominating each scene in a repetitious, aimless cycle. Of course, this in itself can be seen as manifestation of this film’s central theme: political disorganization under capitalism, the stultifying alienation of one class from another, and thus the impossibility of municipal governments’ legislative actions to be guided by any kind of meaningful regard for the people whom they represent. But all of that is formulated through a tiring pastiche of a kind of comedy whose entire affect was built reflexively on the latent awareness of class and what the comedy of manners would then inherently attack. The thought seems to be that this film must explicitly articulate just that dynamic; it does, and we sit there nodding our heads as characters squabble and make remarks like, “My brand of feminism is putting myself systematically in the centre.” The joke is so aggressively grating and transparent that there is no real occasion for engagement with the film beyond it. Everything comes to a neat conclusion, but we’re left feeling ignorant to whatever was the point in the first place.

You can currently stream Jeanne Balibar’s Wonders in the Suburbs on Mubi.

Comments are closed.