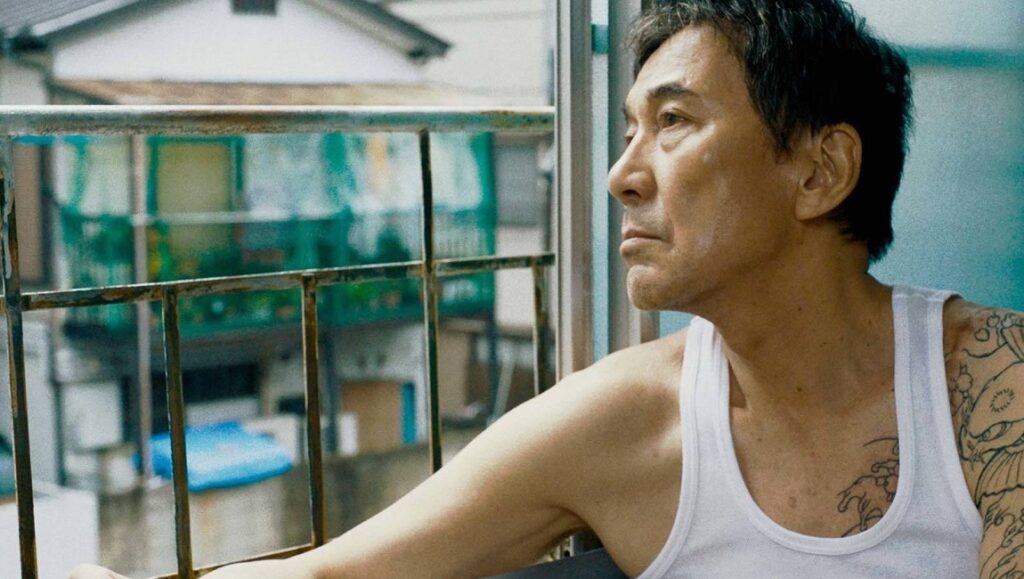

Like R.W. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, Under the Open Sky opens with an aging man being released from prison after serving thirteen years for murder. During his out-processing, the warden glances through the records and, in perhaps an attempt to relieve their unhappy burden, asks if he feels any remorse over them. The man nods, then clarifies his position — not towards the victim, a common “hoodlum” in his words, but for having suffered because of him. Mikami, ex-yakuza and an unloved social outcast played by veteran actor Kōji Yakusho, has vowed to “go straight” ever since, eagerly rejecting the destiny his orphaned childhood and criminal adolescence might have imposed upon him. But the comparisons to Fassbinder’s sprawling adaptation end here: While Mikami’s infantile disposition, imbued with a gruff and childlike innocence, may resemble Fassbinder’s Franz Biberkopf, the trials and tribulations the two encounter in the civilian world bear few similarities: Biberkopf, a common man, undergoes a hellish descent into madness; Mikami, of the underworld, falls a good many times before suddenly picking himself up.

Miwa Nishikawa’s adaptation of Ryozo Saki’s prizewinning novel, Mibuncho, might not have been dealt the fairest hand by being compared to Berlin Alexanderplatz, at less than a seventh of the latter’s colossal scope and runtime. But comparisons aside, Under the Open Sky still proves an increasingly melodramatic work whose quirky sentimentality, masquerading as endearing complexity, seems destined to win over more hearts than minds. From the outset, Nishikawa’s vision for her protagonist’s surroundings is set in stone: society as a whole may prefer not to reintegrate its transgressors, but everyday pockets of humanity usually respond kindly to those who are genuinely interested in rehabilitating themselves. And so begins Mikami’s upward struggle toward a normal life never known to him — he meets an affable lawyer who sponsors ex-convicts as a hobby, then tries leaving behind welfare and landing a job, getting back his driving license, and finding his mother with the help of a television crew. The inability to temper his angry outbursts, however, sees him rejecting the kindness of strangers, roughing up petty gangsters to within an inch of death, etc. — the hallmark of recidivism, essentially. Yakusho, valiantly injecting earnesty and vigour into his character’s rebirth, remains frustratingly subjected to the film’s saccharine generics. More a tiresome collection of calculated emotional investments than an organically developed storyline, Under the Open Sky initially charts a hopeful path, before going astray towards a checklisted, by-the-book formula and nosediving into an inexplicable and unsolicited denouement. There’re only so many bumbling, unhinged, self-pitying tales the genre can take.

Published as part of TIFF 2020 — Dispatch 6.

Comments are closed.