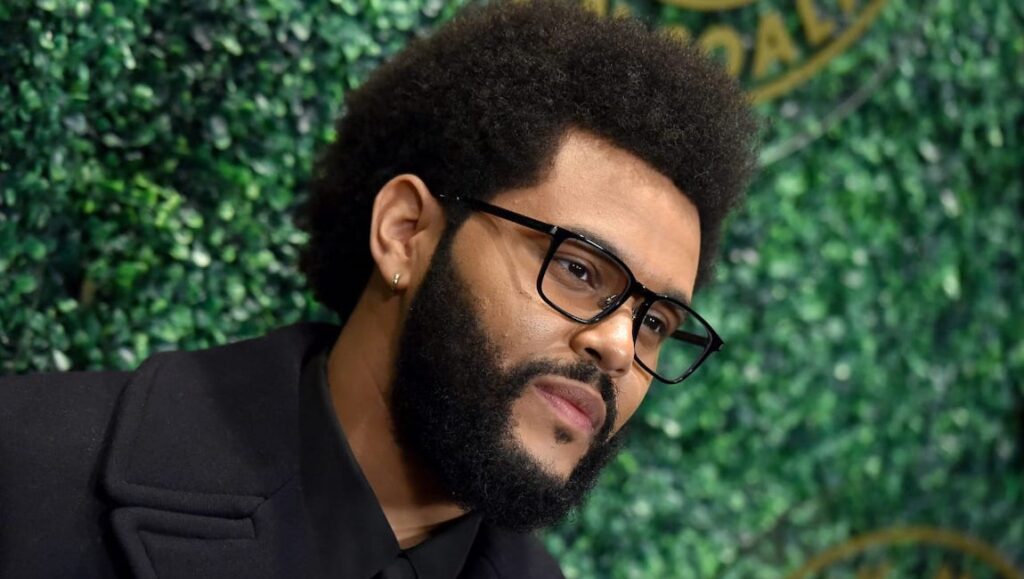

The Weeknd

These days, Abel Tesfaye occupies a pretty elite stratum of the pop music world as The Weeknd, straddling the line between consistent Billboard hits and a relatively solid rate of success with critics. With a large cross-section of the industry eager to work with him and seemingly no label opposition to his indulgent runtimes and relatively frequent drops (they probably find this appealing, actually), Tesfaye is, in this moment, unsinkable and likely will remain so barring some sort of dramatic pivot or career subversion. And so, The Weeknd’s focus has inevitably drifted toward notions of purgatory and the burdens of fame, two concepts with an obvious interconnectedness that have vaguely informed his last couple releases, and which now form the basis for a more literally minded concept album interpretation: Dawn FM.

Picking up from where they left off with their very memed Super Bowl 2021 halftime show, Dawn FM reunites Tesfaye with Oneohtrix Point Never (that program’s musical director), while also inviting Max Martin back into the fold (having become one of The Weeknd’s most essential collaborators at this point). All three assume executive producer responsibility here, overseeing a varied stable of pop and EDM producers whose collective contributions they’ve refined into a fairly consistent sonic aesthetic. Their total efforts amount to a chilly portrait of late-night/early-morning debauchery and reckonings, moody dance tracks that sit at the expected intersection of vapor and ‘80s pop production reclamation. Tesfaye puts his clout to work here, roping in fellow Canadian icon Jim Carrey for a series of eerie monologues that provide the album with its structure, casting the Bruce Almighty star as an otherworldly FM radio host guiding you out of a purgatorial state and into the light. Whether or not the songs in between Carrey’s musings add up to any legible continuity could be debated, which perhaps discredits The Weeknd’s cinematic aspirations here (telegraphed via spoken word interludes from Josh Safdie and Quincy Jones, who’s also on hand to lend legitimacy to this album’s general Off the Wall homage), but otherwise hardly matters.

Dawn FM may lose track of its proposed narrative, but Tesfaye, OPN, and Martin maintain a firm grip on their overall palette and tone, remarkable when considering the number of disparate and significant contributing producers they oversaw for this project (Calvin Harris, Swedish House Mafia… Bruce Johnston?) Not a new or unique aesthetic certainly (OPN has played around with many of these ideas before on his own albums), but one that’s too well-suited to The Weeknd vibe to dismiss, Dawn FM effectively evokes the rock bottom sensation that creeps in after an all-night bender, paralleling this sensation with a perspective aimed at maturation and reconciliation. Which isn’t to say The Weeknd has gotten much tamer, bringing nihilistic new-wave menace to the wonderfully melodic “Gasoline” in his recounting of a bleak Bret Easton Ellis type scene (whose work is echoed in more sentimental fashion in penultimate track “Less Than Zero”), and saving a spot for his classic sexually frank crooning on “Here We Go…Again,” an impassioned R&B sing-along disrupted briefly by an abrupt Tyler verse. Dawn FM’s big themes feel more like gestures than actual fixations for the artists who have masterminded this album, with inconsistencies and redundancies from song to song, but of course The Weeknd’s chic, tortured persona is itself contradictory in a way that inherently justifies this sort of oscillation. But while it’s true that post-Beauty Behind the Madness Tesfaye hasn’t quite figured out how to get a truly great project out of this format/release pace, Dawn FM at least maintains him as a dependable trend rider and craftsman of pop spectacle.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: Pop Rocks

Earl Sweatshirt

Over the past half-decade, Earl Sweatshirt has been saying a lot with very little; or, more accurately, he’s communicated an abundance of personal beliefs and ideals by keeping things frugal. There’s really not much that’s particularly flashy about the Sweatshirt enterprise these days, just a lot of getting to the point and getting to it quickly. As he even puts it on “Titanic” — the closest thing to a banger to be found on his fourth studio album, the Covid-inspired SICK! — he’s going to “give it to you straight, no frills.” Indeed, “no frills” entertainment is what he continues to provide: There’s hardly any crazy boasts, the beats are short and disheveled, only one track has a full-fledged chorus (closer “Fire in the Hole”), and a grand total of zero contain anything close to a hook — there are two credited features (Zelooperz and Armand Hammer), but you’d be hard-pressed to consider those some “big name” gets. Earl’s delivery throughout could best be described as relentlessly sleepy, like if Ghostface took a ton of quaaludes before going into the booth (not assisted by the muffled vocal mixing) — though, flow aside, Earl continues to be an equally expressionistic storyteller, employing the same type of Supreme Clientele-era abstract non-sequiturs that disrupt any sense of linearity to his raps. There’s a subtle keenness to Earl’s pen game that’s never been laugh-out-loud funny, but has grown sharp, pointed, and angry through the years, articulated most cogently here on the pensive title track. His music, in turn, has become spartan to the point of complete insularity, shaggy-dog self-reliance taken to its logical conclusion.

But while this parochial approach suited Some Rap Song’s downward spiral progression — where the general terseness was mandatory given that album’s emotional trajectory — it creates a void at the center of the disjointed SICK!, which is elusive for its own sake most of the time. Lacking any real sense of cohesion, the project is forced to rely on each individual track’s strengths (if he didn’t already use it, calling this collection “some rap songs” would have been far more fitting), where, frankly, the line between lo-fi and low effort is now getting increasingly thin. Take “Tabula Rasa,” which keeps stopping and starting again for no discernable reason, where guests E L U C I D and billy woods certainly bring their A-game, but are left stranded against a sea of general indifference; it’s captivating in the moment, but lacks any purpose beyond fulfilling these basic aspirations. At a scant 10 tracks — including an interlude that’s structurally indistinguishable from most of the other “serious” songs — SICK! all too regularly gives off the impression that it’s content with doing as little as possible, where the minimalist tendencies of its central artist are starting to feel like defects instead of virtues. While there’s still certainly plenty of pleasures to be found with Earl’s raggedy inflections (the way he murmurs through “’03, momma rockin’ Liz Claiborne” is both endearing and amusing) and deft wordplay, the degree to which everything else around his music continues to produce diminishing returns positions him and his artistry at a distinct crossroads.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: What Would Meek Do?

FKA Twigs

After the melodramatic heights of 2019’s Magdalene, it’s not so surprising that FKA Twigs would aim to lower the stakes for her follow up, this time walking in the footsteps of Drake’s More Life and putting out a faux-mixtape of her own (Jorja Smith feature and all), entitled Caprisongs. As was the case with that Drake project, Twigs uses the “mixtape” label here as a means of alleviating release pressures and characterizing what is still ultimately an album as a looser, more freewheeling effort. It’s a sunnier one too, leaving behind Magdalene’s chilly textures and mythic heartbreak in favor of more traditional pop production and straightforward, inspirational sentiment while making room for an abundant guest list, having grown increasingly more comfortable with sharing her stage over the last couple years. Caprisongs also marks a step forward in Twigs’ self-expression, never a lyrically coy artist exactly (early hit “Lights On” succeeded in part off the merit of her directness), but certainly one who has actively disguised and obscured messaging through vocal manipulations and subversive pop production. This project, on the other hand, relies more on the clear, legible refrains and anthems more readily associated with Top 40 contenders.

Streamlining ever so slightly from Magdalene’s sprawling all-star lineup of producers, Twigs has teamed with dub/tropicália producer and Rosalía collaborator El Guincho here, the pair sharing executive producer responsibilities with credits on nearly every track (Koreless, returning after his contributions to “Holy Terrain” and “Sad Day”, picks up the slack otherwise). As such, Caprisongs’ aesthetic is weighted towards the Alegranza producer’s preferences, though he and Twigs embrace an excited curiosity, shifting in and out of genre from song to song, playing around with afrobeat, grime, dancehall, U.S. R&B, etc. (again, a bit reminiscent of Drizzy’s More Life tape…). On many of these tracks, Twigs and El Guincho seem to follow the lead of the invited guest, pitching her against a mostly U.K.-centric collection of artists (the exceptions being Nigerian rapper Rema and Canadian crooners Daniel Caesar and The Weeknd) who specialize in these genres and stylings.

Rejecting the introspection and flagellation of Magdalene, the songs compiled here instead subsist off the energy of female empowerment, Caprisongs revealing itself to be a different sort of breakup record over the course of its 45 minutes, indulging in a playful aggression toward the famous men who’ve wronged Twigs in recent years (with varying degrees of severity, of course). Having made a stirring spectacle out of her wronged womanhood, Twigs now turns celebratory, inviting fellow female artists and friends to monologue about masculine cruelty and indifference, a la Jazmine Sullivan’s recent Heaux Tales. These anecdotes, while hardly revolutionary, offer some levity and a guiding ethos to Caprisongs that ultimately casts the album as the flipside to her previous, more demure releases that came before: “oh my love”’s “Everyone knows that I want your love / Why you playin’, baby boy, what’s up?” acts as a sort of progression from “Cellophane”’s painfully intimate “Why don’t I do it for you?” That said, Caprisongs also lacks Magdalene’s weight, by design certainly, but Twigs’ commitment to pop immediacy doesn’t feel entirely pure yet, resulting in a handful of excellent singles (Arca contributions “tears in the club” and “thank you song” are particular standouts in this regard) and a few more songs that occupy the necessary space to constitute a full mixtape. Still, a brighter fun-minded take on the FKA Twigs project has its appeal, and Caprisongs understands that, to some extent, this has been the direction many fans have been anticipating her turn toward. Presumably a dry run for something a bit grander, this latest project, if not fully at arrival, at least allows Twigs to redirect her narrative and imagine new horizons for herself.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: Pop Rocks

Aoife O’Donovan

Though recorded in lockdown, Age of Apathy dreams of motion. Songs catalog bus routes and rearview mirrors; characters speed down backroads, ascend in elevators, and keep a watchful eye on the movements of celestial bodies. In the title track, the narrator blasts Joni Mitchell from the car radio. For Aoife O’Donovan— singer, songwriter, and professional itinerant— Mitchell can’t help but be a lodestar and patron saint: Another restless poet who quests for connection and seeks refuge in the road.

Indeed, wanderlust seems like a habit of being for O’Donovan, whose own discography is a series of detours and crossed paths. She has made fine albums as a solo artist, as the leader of Crooked Still, and as a co-founder of I’m With Her. Despite its transitory concerns and the mitigating circumstance of its creation, Age of Apathy is her most grounded and assured album yet. It’s sung with grace and passion. It’s written with an intuitive sense of story, poetry, mystery, and thematic connection. And it’s produced with warmth, texture, and detail by Joe Henry, a man who can produce great singer-songwriter albums in his sleep, yet still finds new ways to distinguish his work. Here he wrangles a team of musicians, including go-to studio hands like drummer Jay Bellerose as well as marquee guests like Allison Russel, all of whom recorded their parts remotely. You’d never know of the album’s piecemiel provenance unless you read it somewhere: It sounds as elegant and as seamless as if all the parts were recorded live and in real-time.

Age of Apathy is an album that sounds uncluttered and direct, but which surprises with new layers on each listen. In some other corner of the multiverse, this album might have been rendered with fusty austerity, and O’Donovan’s melodies are so winsome that they probably could have supported it. Blessedly, she and Henry chose a more generous route, populating these songs with ear candies and sensual delights: Listen to the woodwinds that snake through “Sister Starling,” to the burnished soft-rock harmonies on “B61,” to the open-air finger-picking that brings glistening grace notes to the devastating “Prodigal Daughter.” The album’s grace and poise never shake, not even when it takes surprising detours into scuffy, minor-key rock (the brooding “Lucky Star”) or summons the ghosts of Lilith Fair (the lilting “What Do You Want from Yourself?”, as confrontational as its title). Varied, textured arrangements give the album depth and character, but they don’t distract from O’Donovan’s pliable tunes and clear, confident singing.

The production mirrors the songs themselves, which churn and thrum with uncertainty and dislocation. O’Donovan’s characters often find themselves caught in time’s riptide, doing their best to make peace with bygone days. “What Do You Want from Yourself?” answers its own question with jarring clarity: “What do I want? I want to be what I wanted to be in 1993.” There is a similar struggle to reconcile with the past in “Prodigal Daughter,” which downplays the Bible’s aspirational grace with a more measured psychological realism: “I know forgiveness won’t come easy,” O’Donovan admits. A few of these songs drop anchor in specific times and places — “Elevators” paraphrases Bono’s famed reminder that “outside, it’s America,” while “Age of Apathy” is set in the long shadow of 9/11— but O’Donovan is just as comfortable writing in allegory and myth, as in a provocative song where she exiles herself from a town called Mercy. In “Passengers,” an album-ending guitar jam with Madison Cunningham, the planets are in motion and we’re all just along for the ride. But a more persuasive moment comes in the title song, which posits love as the true center of gravity: “When nothing’s got a hold on you / If you need someone to hold, you can hold me.”

Writer: Josh Hurst Section: Rooted & Restless

Burial

The defining characteristic of William Bevan’s 5-track Antidawn — an EP in name only; this is his longest effort since 2007’s Untrue — is one of atmospheric ethereality, where the music is so weightless and measured that the basic act of listening becomes strenuous, an ordeal in attempting to hold onto anything of momentous note. The colorless soundscapes are sparse and desolate, lacking in tangible form and haunted by decaying, detailed textures (record crackles, warbled voices, dripping water, hissing pipes, clicking lighters, etc.) that fade in and out of the percussion-less mix at a moment’s notice, ones that help instill some semblance of organized structure. There’s a lot of negative space/breathing room on any given song here, to the point where serene silence becomes an integral part of the musical compositions themselves. There are a few melodies, but they’re hidden in plain sight, abstracted, and silently looping back around over and over again until their presence is finally felt by sheer repetition. The mood is, generally speaking, somber and sedated; the overall listening experience is frigid and gelid, akin to a long, solitary walk on a snowy winter night. Except, here, the environment feels more like a ghostly wasteland, once joyfully inhabited and now, ever so slowly, transitioning into a realm of deterioration, currently existing in an in-between state of being — especially fitting, given that Antidawn itself doesn’t neatly fit into any one predetermined category or genre (sound collage? field recording? ambient? electronic?). If definitive descriptors were required, then one could easily label this as Burial’s most patient, quiet, and experimental release thus far — and so, as it stands, it’s yet another curveball from our least calculable working musician.

Wading through this uncharted territory, at least on a first listen, can feel like an uneventful journey: the pay-offs provided aren’t that grandiose — usually culminating with billowing vocals or a sensory-charged element that slowly simmers — nor do they call much attention to themselves. The EP starts at 1 and, at the absolute max, ends on a 2.5. Compared to any number of scattered singles released before this extended play — or, to be fairer, the somber cuts from Untrue — Antidawn’s material could even seem outright boring when immediately contrasted to the likes of “Dog Shelter” or “Night Bus.” But since this is, again, a record defined by its sonic ambience, these types of judgment calls are a bit premature to lob after only one spin. Since the key aspects of each track are so amorphous and ambiguous in their temperament, each new listen allows for a different interpretation; the general oppressive vibe remains the same, but the granularity of each track unfurls with a different register each time. And so it’s ultimately up to the listener to derive meaning from apparent meaninglessness, to form their own connotations from the slivers of provided denotations (the cover art, however one interprets it, becomes a starting totem for this personal elucidation), and to venture through the unknown at their own pace and speed. It’s a bitter, cool expedition, a crossing not for the faint of heart; even for those willing to invest the needed time and attention, some additional consideration may still be required, but the rewards are rich.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: Ledger Line

Cat Power

Cat Power made a name for herself across not only an extensive solo career, but according to her knack for covers. Her first record of such material (2000’s The Covers Record) was a huge success, with multiple songs being featured in films throughout the following decade. Now, over two decades later, she has returned with Covers, an album that largely sets out to do the same thing. If the sign of a good cover is capturing the spirit of the original while bringing your own flair to the track, her latest is certainly full of these successes.

Given her predilection, it shouldn’t surprise that covers have been a mainstay of the Cat Power live show for quite a long time. While some of these operate as an outro or accompaniment to one of her originals, many of them stand as notable works in their own right. It’s an approach that sticks on her latest record: take, for example, her cover here of Frank Ocean’s “Bad Religion,” which imbues much of the melody of her track “In Your Face.” This process of adaptation and transposition makes for an interesting, textured listen, as pieces of the original are clearly gleaned in what has ultimately become an utterly new song. Other covers are a little more straightforward, like Nico’s “These Days,” an oft-covered track that doesn’t necessarily present anything new in its rendition, but still registers as a pleasing listen. But even cuts of mild ambition testify to Power’s eclectic taste, with covers from modern artists like Ocean and previous collaborator Lana Del Rey butting up against classic artists like Billie Holiday, with a little bit of everything in between. Continuing her tendency toward introspection here, Cat Power also covers her own song “Hate” from album The Greatest, retitling this new version “Unhate.” Re-working songs is a part of her process, she claims, and she treats everything she’s written as a fluidity, an opportunity for a new canvas in the future. The result is a sound cut through with the deep emotion of reflection and growth.

There’s a definite ceiling for something like a covers album, but Cat Power seems intent on breaking through with each attempt. While most artists would flounder under the weight of such a task, wearing another’s songs like clothes that are too large, Power instead relishes the opportunity for artistic cosplay, retaining her signature while also finding inspiration in the work of others. Her records of original music are of course always a welcome development, but what Covers proves is that where most artists might utilize such a record as a bridge project before dropping new material, Cat Power instead sees ample opportunity to continue advancing her sonic evolution in impressive fashion, with just a little help from others.

Writer: Andrew Bosma Section: Ledger Line

Punch Brothers

A terrific standalone album that’s perhaps done a disservice by its concept, Punch Brothers’ Hell On Church Street is as thoughtful and progressive as the band’s albums ever are. As a tribute to one of their key influences, Tony Rice, the band performed the entirety of Rice’s landmark album, Church Street Blues, at a festival in 2019; banjoist Noam Pikelny then encouraged his bandmates to record their reinterpretation of the album in full. Church Street Blues, then, is an album of covers — purposefully chosen and expertly performed by one of the finest guitarists in the history of Bluegrass music — which means that Punch Brothers tasked themselves with covering a covers album.

Given this setup, it’s to the band’s credit — and is a testament to their technical brilliance, which remains unmatched by any of their contemporaries — that they have the chops to make Hell On Church Street into an album that’s full of surprises. The arrangements on Bob Dylan’s “One More Night” and Bill Monroe’s “The Gold Rush” are not overly beholden to Rice’s, while their version of Jimmie Rodgers’ “Any Old Time” takes a familiar standard in wholly unexpected directions. The variations in tempo and dynamic range on opener “Church Street Blues” immediately make it clear that the band understands that paying tribute to a figure like Rice demands that they take creative liberties with their approach. The band’s fearlessness is part of their brand at this point, and that makes Hell On Church Street a riveting listen. Still, Rice’s Church Street Blues is a genre classic for good reason, and Punch Brothers’ concept here does invite comparisons that, if not necessarily unfavorable, make for the first Punch Brothers album that isn’t a masterstroke of pure creativity and ambition.

Writer: Jonathan Keefe Section: Rooted & Restless

Comments are closed.