Tsui Hark presents something of a glorious contradiction, the kind that nevertheless hewed closely to the norm in the crazed grandeur of Hong Kong during the latter half of the 20th century. From the anarchist upstart at the vanguard of the Hong Kong New Wave, to the overseer of a good chunk of the greatest films of the ‘80s and ‘90s as director and/or producer, to the shrewd helmer of some of the biggest mainland Chinese films ever, Tsui’s oeuvre has adapted to and defined each era of film in the area he’s worked in, mixing wild formal artistry with clever populism across a wide swath of genres.

Once Upon a Time in China, which spawned five sequels and a TV series in the following six years, is likely Tsui’s best known and most beloved work, and quite fittingly comes the closest to reconciling, or at least incorporating, all his seeming contradictions. In the process, it also forms one of the pivotal portrayals of the historical figure Wong Fei-hung, a physician and legendary practitioner of the Hung Ga martial arts style who lived in Guangzhou/Canton during the turn of the 20th century. His fame only grew after his death, thanks to the more than 100 films and television series that have featured him; Kwan Tak-hing played Wong in the majority of these films, but other notable works include films by Lau Kar-leung that starred Gordon Liu and the subversively parodic Drunken Master films starring Jackie Chan.

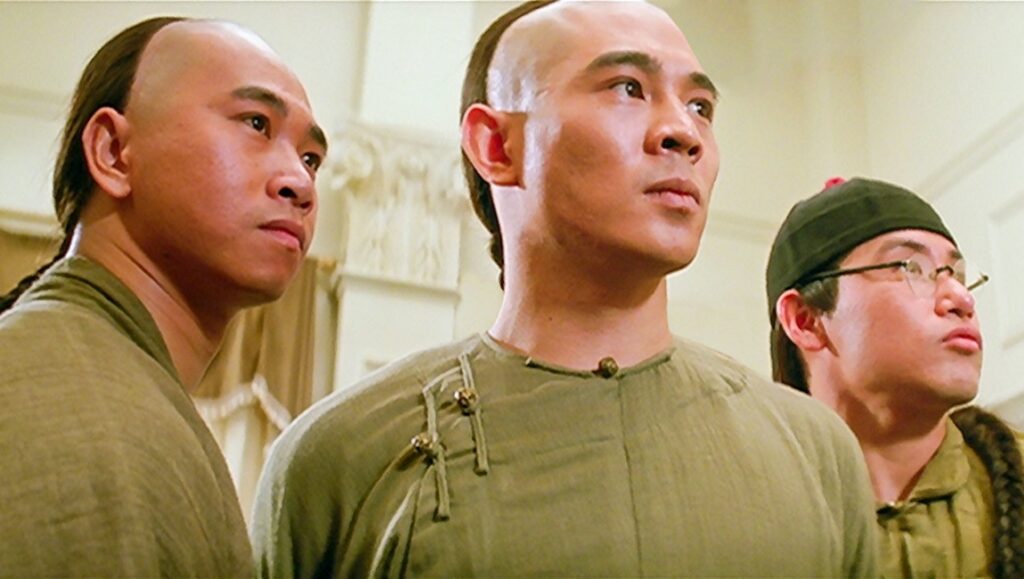

Here, Wong is played by Jet Li, and it’s worth comparing the dichotomy of the Chinese and English titles: Once Upon a Time in China puts the film in direct lineage with those epochal, nigh-mythical works of Leone, whereas the Chinese title, Wong Fei-hung, puts the folk hero at its center. The resulting film certainly has something of the sprawl of the former — running 135 minutes — and the ultimate focus upon the latter, but it also remains resolutely apart from those expectations, or indeed any preconceptions that might have applied to it from either of the artistic/commercial axes.

Even the question of the time in Once Upon a Time in China is in question: it takes place sometime in the late 19th century, and certainly before the fixed date of September 1895 that Tsui’s equally masterful Once Upon a Time in China II is set in, but otherwise its setting seems to float, taking place in a nondescript time of stasis within Wong’s native city of Foshan, where he trains disciples at his medical clinic Po Chi Lam. That stasis, of course, has come with more than its fair share of compromise, colonialism, and corruption: numerous foreign forces, including the British military, an American official, and Jesuit missionaries rub shoulders with the Chinese inhabitants.

Within this diverse mix, a cascading series of character arcs fittingly comes to fruition. Chief among them is Leung Foon (the great Yuen Biao), who arrives in Foshan with aspirations of both acting in the troupe that he performs menial tasks for and bettering his martial arts skills. He provides something of a ballast for Wong’s character, who presents something of a conundrum for Once Upon a Time in China: for a film packed with so much incident, it presents little in the way of conventional narrative or development for its ostensible hero. True, Wong faces the encroaching forces of Western modernization in both the antagonists and his 13th Aunt Siu-kwan (Rosamund Kwan), who has returned after an extended time and has long been enamored with him. But the change in his perspective is in a sense inherited from the characters around him, a response that arises out of his steadfast, unyielding principles and commitment to a conception of China deeply rooted in ancient traditions.

Those traditions are under attack from both without and within: the nominal principal antagonists are the Shaoho gang, who terrorize the local population and cause trouble for the local militia that Wong leads. Their mercenary aims lead them to ally with Jackson, the American official, agreeing to sell Chinese women as forced prostitutes for toiling Chinese laborers in America in exchange for Wong’s demise, and together the two form the forces of pure evil in contrast to Wong’s pure good. But in a certain light, Once Upon a Time in China’s most compelling dramatics revolve around a more indefinite approach to the changing tides, the little, even well-intended aggressions like the impromptu competition between restaurant performers and Christian priests to see who can perform louder.

With the exception of Wong, each character to some degree represents this push-pull between tradition and modernization, steadfastness and capitulation. The most pointed example is penniless martial arts master Iron Vest Yim (Yen Shi-kwan), who eventually allies himself with the Shaoho gang and seeks to defeat and kill Wong to establish his social and economic position. Leung very nearly follows a similar path, and it’s in moments and arcs like these that Tsui’s commitment to his characters and the overarching issues they suggest come to the fore. The characters are allowed to be petty, conflicted, and even extremely morally questionable at times, and the horror of certain moments — especially one where British soldiers open fire on a crowd of innocent Chinese people — is lingered upon in a way that feels necessary to establish the political stakes in such a fraught climate.

Of course, all of this happens in between some awe-inspiring action sequences, which are as notable for their virtuosity and grace as they are for their busyness — the famed ladder fight between Wong and Yim also finds the time to incorporate a bevy of Shaoho gang members who try to shoot Wong from an upper level. Tsui’s control of the rhythms here is key, frequently using longer swooping takes interspersed with both quick cutting and slow-motion that shows off the flowing nature of Li’s style, influenced by his mastery of wushu that reflects a different influence from the martial arts that the real Wong pioneered. That dichotomy almost mirrors the final moments of Once Upon a Time in China, where a balance is struck between the conflicting impulses that have flooded through the film at large. Redemption and adaptation, not unlike Tsui’s own through the years, asserts itself with vigor, but the sentiment of nationalism and the hope for an end to colonialism remain as potent as ever.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.