In the pantheon of late-19th to early-20th century intellectuals, there are few with such starkly opposing views as Sigmund Freud and C.S. Lewis. At most every intersection on questions of morality, sex, and faith, the pair diverged. Though the two never met, their corporeal incarnations have nevertheless been used as vessels to explore their various arguments about the nature of reality in Freud’s Last Session. The film, adapted from a play which was first based on a book, The Question of God, does little to justify its farce. It’s an appealing idea to cast two giants against each other, as one might conceptualize something like Alien vs. Predator for philosophers. What this equation fails to consider are the odds stacked against a movie whose crux is a philosophical debate it refuses to grant depth. Though the pair clash on the topic of Lewis’ belief throughout the film, there is no point at which the film makes clear who is winning the debate. The audience, entering a cage match of the minds, leave as they entered — having not absorbed a single hit during the brawl, which is staged more like a play-date. This act is not a revelation of history, philosophy, or of cinema but rather a fantastical account of one scholar’s views of these men, poorly remodeled into a Hollywood structure.

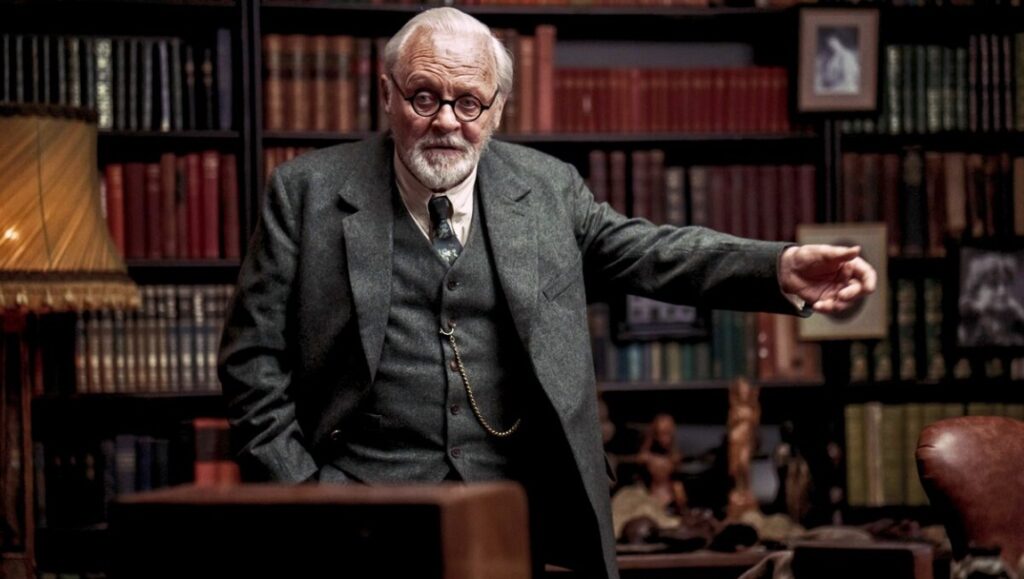

Freud’s Last Session takes place against the backdrop of the beginning of World War II, as Freud (Anthony Hopkins) nears his deathbed and a young Lewis (Matthew Goode) enters into Freud’s home to challenge his conceptions of faith. Freud, ever the atheist, is willing Lewis to change his mind before death. Though Lewis makes several passes, most of their conversations end up precisely where they began, and those that don’t are interrupted by the crudest of backstories suddenly appearing out of their minds. On the rare occasions that the two do genuinely engage with the other’s ideas, a stalemate is always drawn on lines of the grief both have endured throughout their lives: Lewis, a man haunted by his post-traumatic stress, and Freud, a man who finds himself spiraling after the death of his daughter and grandson, being faced now with this finality himself. The actors, at least, offer assistance to the flawed conceit; for a man with a mythos as expansive as Freud to be rendered with such immediacy and delicacy is a testament to Hopkins’ chops, and Goode acquits himself well with the largely anonymous figure of Lewis, providing the audience with a complicated portrait of a man known only as a saint to many.

But Freud’s Last Session is nonetheless baffling for its refusal to allow the men to actually debate for any prolonged period of time, or to conduct an argument of any depth beyond the witty remarks they can make at the other’s expense. Early on in their arguments, the radio announces that more than 20,000 have died in just a few days as a result of the encroaching war. Lewis remarks in bewilderment, “20,000 killed in just two days. Almost impossible to take in, isn’t it?” Freud replies, “Must be more of your god’s mysterious ways.” And the scene moves on, with no room for further interrogation of the idea that Lewis’ god would allow this to happen, nor room for Lewis to defend his faith in such a god. What’s even more confounding is the film’s decision inability to stick to the very simple, very enticing grounding point of these interactions between Freud and Lewis. For every few moments we get with these figures, we are given time with Freud’s daughter, Anna (Liv Lisa Fries), whose affair with another woman serves as grounds for Lewis and Freud’s debates around human sexuality; Anna Freud is a fascinating historical figure in her own right, well deserving of her own film rather than being shunted into the B-plot of a movie bound for the wheel-in monitors of bored high school classrooms.

And indeed to the schools this film will go! Its inoffensive lack of ground makes it the perfect fodder for a generation clinging desperately to its “neutrality.” The neoliberal age is one defined by its compromises, its placating to both sides of issues which must have a definite answer. Whether it be issues of climate, sex, or genocide — there is a middle ground available to benefit all but those who suffer. Though the topics at hand in Freud’s Last Session are in some sense much less immediate, the main item up for debate being the existence of god, the film still suffers from its insistence that everyone is capable of having their cake and eating it too. It would be preposterous to suggest that any one film should make an attempt at a definitive answer as to the questions of humanity’s purpose, but the quaint ushering of disagreements for the sake of peace often carves a far deeper cut than to allow these arguments to reach their logical ends. For all its posturing as a potential reconciliatory force for a divided people, its lack of insight into these debates cements this film as one better left to the imagination.

DIRECTOR: Matthew Brown; CAST: Anthony Hopkins, Matthew Goode, Liv Lisa Fries. Jodi Balfour; DISTRIBUTOR: Sony Pictures Classics; IN THEATERS: December 22; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 48 min.

Comments are closed.