Sable Island is a thin crescent of land (twenty-six miles long and less than a mile wide) located southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia. This sandbar planted at the lonely edge of the Atlantic continental shelf, burdened by histories of shipwrecks and ghost stories, is home to a quietly resilient ecosystem; horses roam wild, seals lounge in the sands, beetles scurry in the underbrush, and one naturalist Zoe Lucas keeps watch of it all as both guest and de facto caretaker. In Geographies of Solitude, Canadian documentarian Jacquelyn Mills delicately enters Lucas’ world. Shot on soft 16mm, the film aesthetic mirrors Lucas’ warmth, calm, and clear-eyed affection for the environment and her place within it. Meanwhile, experimental sections of the film allow the island to speak to us in a more direct way, and even Mills’ matter-of-fact descriptions of these invigorating fragments read like poetry: “horse hair, bones, and sand, exposed in starlight, developed in seaweed,” she notes over a particularly intense segment. And so, Geographies of Solitude is an organic balancing act between the more conventional documentary forms (somber reflections at the mountain of plastic washing up on the island’s shore) and something weirder and wilder (ambient electronic compositions constructed out of snail song) altogether.

More so than a narrative disruption, Mills’ experimental digressions are, in effect, an attempt to probe and reflect the push and pull at the heart of Lucas’ environmentalism. Moments like Lucas’ introduction into the film, walking with a lantern amidst a pitch black sky perforated with stars; at once wholly a part of the environment, just another gleaming light, and yet distinct, somehow apart from the natural fabric of the place and relegated to forever be an observer. The true solitude of the film’s title reveals itself slowly, in the uncomfortable middle ground that we seem to occupy somewhere between Mills’ gorgeous compositions: the rugged mosaic of horse skulls and the cloying primary colors of plastic detritus. These are the grim undercurrents (72% of collected bird corpses have stomachs filled with plastic, as Lucas explains) flowing beneath the tender and soft exterior of the film, whose presence in someway recalls the more confrontational approach of Lucien Castaing-Taylor and VérénaParavel’s Leviathan, an avant-garde rumination on the fusion of man, animal, and machine on an industrial fishing ship.

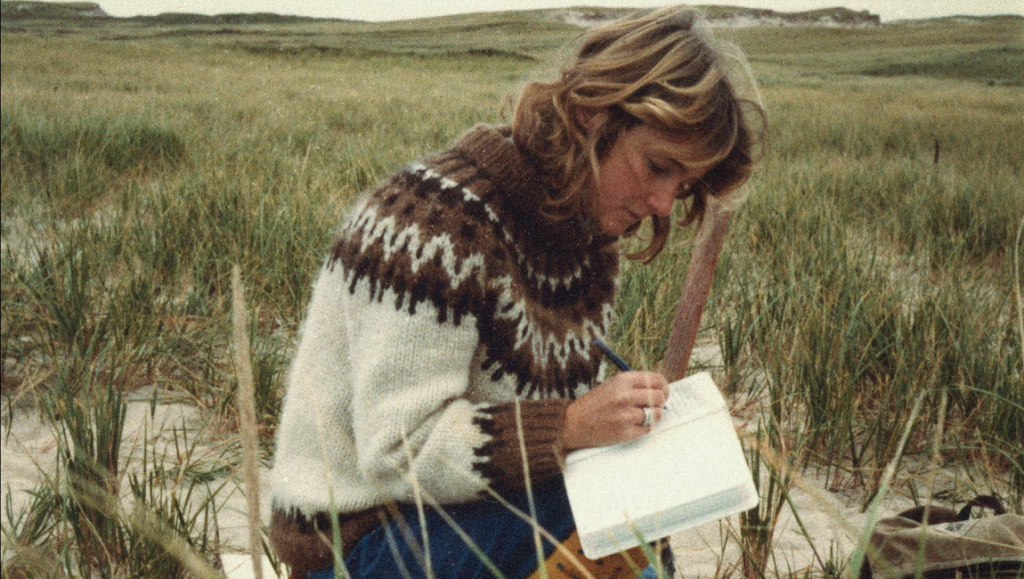

A similar type of fusion takes place here, within the bounds of Lucas’ work, whose spreadsheets capture the scale of the island’s ecosystem in startling detail, from horses (the living and the dead) down to ladybugs, spiders, and flowers, a taxonomy that, just one worksheet over, shifts towards a seemingly endless hoard of plastic washing up on shore ranging from balloons, shampoo bottles, and microbeads. Brand names are listed out like genera. Much like the Frankensteinian visions of Leviathan — which imply the domination of industrial machinery not simply over land and sea but over us as well — Geographies of Solitude shares a somber melancholy over the impending, irreversible damage we have wrought to our natural ecosystems. A strain of positivity nevertheless lingers throughout and expresses itself, however guarded, through Lucas’ emphatic passion for her work. In a rare fragment from the past, intercut into the film, we see her over thirty years ago giving a tour of the island to the legendary Jacques Cousteau. Lucas is immediately recognizable by her spirited enthusiasm, the perseverance of which, to this very day, attests to a resilience sourced deeper than any individual ambition. There now on Sable Island, with its howling gale, walking amongst the seals and horses, a backpack dappled in snow, is a woman who bears down her life’s work with the determination predicated on a more natural instinct: survival.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 4.

Comments are closed.