We at InRO have never covered the Portland International Film Festival, but we’re all about evolving in 2020, and so here is our first ever dispatch (and the first of several we’ll be publishing across the next week). Featuring a slate packed with fall festival regulars and an intriguing mix of under-the-radar debuts, there is no shortage of material for us to dig into. This dispatch focuses primarily on festival regulars from the past nine months, including: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s To the Ends of the Earth, Pedro Costa’s latest experimentation (Vitalina Varela), and Armando Iannucci’s period pivot (The Personal History of David Copperfield), among others.

To the Ends of the Earth

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has been here before. Not to Uzbekistan, where his newest film is set — and which is indeed new territory, geographically speaking — but to this border zone openly contested by opposing modes, genres, and moods. To the Ends of the Earth begins as a kind of travel film, or more precisely, as a document of a TV crew failing to produce one: The host, Yoko (Japanese pop singer Atsuko Maeda, now a regular Kurosawa collaborator), can’t muster the pep required to perform her role as world ambassador for audiences back home, who are conditioned to believe that foreign lands uniformly provoke wonderment and irrepressible perkiness, when in fact disappointment and displacement prevail. Feeling lost, and in the face of escalating, if minor, production troubles, Yoko abandons the shoot, strikes out on her own, and penetrates, with mounting dread, ever more uneasy terrain. She might have some reason to be afraid given her tour guide, though Kurosawa’s reputation as a J-horror pioneer remains frustratingly overblown: More often than not, he journeys to different destinations altogether, where fear — of the other, of the self — is merely a byway on the path to transformation. A midway sequence that suspends Yoko in the dizzyingly alien halls of Uzbekistan’s national opera, and concludes when she emerges from this thicket of arabesques into an empty theater, where she takes the stage and pierces the tension with an aria, is the film’s trajectory in ornately crafted miniature. At this point, her sojourn only half completed, Yoko has discovered that suspension — between home and abroad, trembling and ecstasy, the horror movie and the musical — leaves a person, or a work of art for that matter, restless, uprooted, and potentially quite alone. But she has farther to go before she will learn that such feelings are the iron upon which explorers are made. Kurosawa learned this long ago, of course, and To the Ends of the Earth allows the director to once again test his mettle in risk-filled territory, territory that he alone seems willing to hazard — no one else is making movies like this. The final moments do, however, grant him the gift of a fellow traveler: as Yoko crests a hill, she finds herself folded into the natural splendor of an ancient mountain chain, and, suddenly, the sound of an adventurer’s spirit, newly forged, rings out clarion across the range, reaching — the film along with it — a previously unknown summit. Evan Morgan

Fire Will Come

Oliver Laxe‘s Fire Will Come is a film built upon two contrasting modes. On one hand, there’s its ethereal, otherworldly atmosphere, seen most clearly in the film’s hypnotic, Vivaldi-backed overture of trees being felled in a fog-shrouded night. On the other, there’s its essential, ontological realism. Centered on Amador Coro (Amador Arias, a former forest warden playing a variation of himself), an arsonist recently released from prison, the film attentively depicts his modest home life with his elderly mother Benedicta (Benedicta Sanchez) in the mountains of rural Galicia. The workings of their small farm are illustrated in detail, with ample time expended on even the treatment of an injured cow — a choice that draws attention for its essential irrelevance to the main plot. For a time, Fire Will Come mainly functions as a subdued character study: tensions abound, but Laxe’s inclination is to defuse them, often by defaulting to silence and stasis. That is, until the climactic conflagration portended by the title, for which Laxe, his crew, and local firefighters underwent months of preparation — and which is no less devastating or fearsome for it. With a scale far beyond that of the ones in Roma or Too Late to Die Young, the wildfire that overtakes Laxe’s film is impossible to control. And if it in the end feels as if the director had little interest in filming anything other than the fire — and merely constructed the pretense of a story in order to capture it — Fire Will Come at least retains a kind of documentary-based fascination. As the Galician countryside goes up in flames — and any narrative interest with it — all that remains is the director’s own relationship to his homeland, which he describes as having “a beauty so intense and unpredictable that it knows no restraint.” Lawrence Garcia

Vitalina Varela

Winner of this year’s Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival, Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela immediately asserts itself as an artistic and conceptual distillation, if not culmination, of a career that has folded portraiture, theater, anti-colonial politics, and class solidarity into a cinema that understands itself as a work that persists under, if not against, ‘the cinema’. While refining Costa’s artistic and conceptual sensibilities, this latest film may be most notable, at least to those familiar with the director, for its changing of the temporal rules that have up until now defined the occupants of Fontainhas. Since 2000’s In Vanda’s Room, many names and faces have recurred in Costa’s cinema as it has taken the aforementioned community as its object, with the spatial and temporal progression between that film and 2014’s Horse Money being decidedly linear; all of it a witness to an abiding sameness of material and mental degradation in the throes of poverty and the violence of history. Yet in the starkest of contrasts, Vitalina Varela asserts itself as an interruption of such linearity. While still following the director’s well-known docu-fictive strategies, the film—which suspends the temporal progression of his filmography at large and acts as a spiritual prequel or parallel temporality to the director’s 2014 work, presents events described by Vitalina in that film, chiefly her arrival in Portugal from Cape Verde not long after the burial of her runaway husband, as she comes to terms with the facts of his abandonment and the destitution of his existence in Portugal—is the most forceful expression of Costa’s desire, or fight even, in his own words, to “respect time… to be with time, on the side of time” as he and his actors excavate the memories that haunt their waking and dreaming. Horse Money and Vitalina Varela are united as films dedicated to the traumas, secrets, and selective recollections of the people and characters of Ventura and Vitalina—who take precedence in each, respectively—and the attempt to give them back history and the time taken from them. Each film contends with figures and images of the past invading the present of their protagonists, and if Horse Money conceivably ends in failure—a repossession by historical violence—Vitalina Varela, which sees visions or dreams of a young Vitalina in her then under-construction home on the hills of Cape Verde reverberate out of the past into the mind of the older Vitalina in Portugal, is its opposite. “It’s all about the work”, remarks Costa, and fittingly, for the words are not just emblematic of the production itself and the director’s wider philosophy—which is actively challenging cinema and its means of operation and the ends they are directed toward—but of the very themes of the film: the attempt to not only to stand with time but to return agency and free a person to build again. Vitalina Varela will rightly be celebrated for the beauty of its claustrophobic Vermeer-esque, Lewton-inspired compositions; methodical editing; and languorous shooting rhythms, but it is the denouement that confirms the film as a work of extraordinary conceptual and humanistic vision: a movement of character out of frame and a cut that connects a rejection of present isolation with the joy of a Cape Verdean past. In these closing moments, the viewer witnesses a restoration of agency through an uncompromising respect for time; not only might the character have found the capacity to build again, but all the more so might the very person of Vitalina herself have—through a seizing of the tools of cinema and its collapsing of the rules of time—returned her life to herself. Matt McCracken

The Personal History of David Copperfield

Armando Iannucci has basically staked his career on writing whiplash-inducing scripts with rapid-fire witticisms that are, structurally, integral to the stories that he wants to tell. In other words, the filmmaker would decidedly not be described as Dickensian or Victorian. Given the choice of pre-twentieth century British literary influences, the humorous neoclassicists and satirists feel like the more obvious sources of shared DNA. But following Whit Stillman into mannerist Jane Austen comedy territory is similarly logical. So it does make some amount of sense that Iannucci would opt — when choosing from Dickens’s considerable catalogue — for the relatively frisky (for this author anyway) David Copperfield, and even more so that he would transform this narrative into something closer to fable. To that end, Iannucci here is as visually playful as he’s ever been: wonky lensing, low-angle push-ins, and fuzzy frame edges all set the tone from the get. Pastels and otherwise muted tones define interiors, paired with frequent displays of drabness and squalor, all lending the film a thematic cushion, and situating its story in more the realm of a yarn than a grim class commentary. That stakes-lowering approach makes for pleasant viewing; it allows the transplanted Iannucci humor to indict without its usual acerbic undertones, and lends cartoonish liveliness to The Personal History of David Copperfield‘s episodic structure. It also means that everything feels a bit breathless and rushed, that ticking off plot points is the dominant screenplay stratagem. In this sense, David Copperfield is still an uneasy fit for Iannucci: the writer-director’s wryness is applied more to visually mirthful signifiers, and to imbuing notability in characters with limited screen time, than to exploring the varied forms of corrupting, societal rot that have been his brand — and that here are mostly played for the requisite arch villainy necessitated by all fairy tales. But if this approach, favoring trifle over nourishment, results in a capped ceiling, that’s really okay, because let’s be honest – Dickens was indulgent. Luke Gorham

There’s an undeniable sensuousness to the surfaces of Bacurau: from the music choices (including a John Carpenter composition, speaking volumes to the film’s influences), to the mixture of genres, and the various twists and diversions that the film takes, cinephiles, especially, will appreciate what Kleber Mendoça-Filho and Juliano Dornelles are up to here. Bacurau takes place in the titular small Brazilian village; the matriarch of the community has just passed, and her funeral and wake provide an opportunity to see the people grieve together. We’re introduced to many of the characters at this point, including Domingas (Sónia Braga), who throws a passionate, drunken tantrum about the recently deceased. Later, this small town suffers through a series of strange problems: the town itself disappears from satellite maps, the internet and phone signals become spotty, the truck that brings clean water gets shot at, and some nearby farmers are found dead in a bloody massacre. Bacurau halfway introduces the element of chaos: a group of foreign paramilitary forces, led by a general played by Udo Kier, are slowly destabilizing this village, for reasons that aren’t immediately clear. These plot points serve to constantly shift things around, especially in the second half of Bacurau, setting up some fantastic sequences of strategic violence, and even touching on political talking points. But whenever the film focuses on the outsiders, instead of the villagers, any richness and uniqueness deflates, as the filmmakers succumb to the exact clichés that one would expect, and write derivative dialogue sequences that seem to be transplanted from this film’s influences. There’s a singular universe in Bacurau, the village, and the interruption of “the villains” of this story impedes its construction and depth, hindering what at first feels like a unique genre film that’s rich in local color. Jaime Grijalba Gomez

Atlantis

With Atlantis, director Valentyn Vasyanovych (also editor and cinematographer here) has created a dystopian nightmare out of the Ukraine’s current political and social quagmire with Russia. Like some kind of unholy amalgamation of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Sergei Loznitsa’s 2018 film Donbass, Atlantis imagines a futuristic, liberated Ukraine that nevertheless is in ruins. Huge swathes of land are uninhabitable, drinking water is scarce, and bombed-out factories litter the landscape (any similarities to Chernobyl are clearly intended). Of course, part of Vasyanovych’s point here is that, despite the vague sci-fi genre trappings, things don’t look that different from the normal stages of late capitalism (even more intriguing? The notion that this nod towards speculative fiction gives the film, and filmmaker, some cover from government meddling. Regardless, Mad Max Fury Road this is not). Atlantis consists of 28 individual scenes, each a discrete unit separated by a hard edit (with one exception involving an uncharacteristically gentle dissolve). By my count, 5 of these scenes involve camera movement of some sort; otherwise, the compositions are locked down master shots, with a shallow depth of field that creates a kind of large-scale tableau. It’s a disturbing distancing effect, as we watch Serhiy (Andrii Rymaruk), a former soldier dealing with PTSD, first working at a huge metal refinery and then taking to the road to deliver potable water to areas affected by the war. Along the way, we gradually learn a few scattered details about what has happened. But traditional plotting isn’t particularly important here. Serhiy eventually meets Katya (Liudmyla Bileka), an archaeologist who now volunteers with an organization that digs up, and identifies, bodies of soldiers who were left behind enemy lines during conflict. In her words, she is giving the families of these men closure, allowing the war to finally end for them. The great lost city of Atlantis has been part of the popular imagination for centuries; here, the myth is reconfigured to suggest a kind of subterranean society that exists just below the surface, a world of corpses, victims of torture and other atrocities. As we watch several scenes of graphic autopsies unfold, in real time, it becomes clear that Vasyanovych is interested in a moral reckoning of sorts, a clear-eyed confrontation with the past. The first scene of the film is an overhead view of three figures beating someone to death, and burying them. It’s filmed in infrared, obscuring the more grisly details and turning bodies into ghastly digital artifacts; the overhead position suggests a god’s-eye view, or a drone or satellite (or an implied audience). The end of the film is shot in the same way, as Serhiy and Katya embrace. By imposing the same visual graphics over a different scene — a scene of great tenderness, it should be noted — Vasyanovych seems to be suggesting that the act of violence that opens the film has colored everything that has come after. Serhiy and Katya are alive, but they haven’t really escaped; they’ve become the ghosts, while the past will live on, whether we want it to or not. Daniel Gorman

Present. Perfect.

Zhu Shengze’s Present.Perfect. is preceded by information about the state of live-streaming in China, making clear its overwhelming popularity in the country — there were 422 million users (known as “anchors”) in 2017. On June 1st of that year, the Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China came into effect, leading to: data localization, stricter censorship laws, and requirements for anchors to use their real names. There’s a quote from the Cyberspace Administration of P.R. China that’s included in the film, explaining the apparent fear in the homogenization of the real world and the “virtual” world. It establishes what Zhu is trying to accomplish with Present.Perfect: to push back against any negativity surrounding live-streaming and make evident how these platforms are, in fact, providing unflinching portraits of the Chinese population. That many of the anchors are far from the “exemplary” people that a country may want as national representatives (one person has muscular dystrophy, another is a burn victim, one just likes to dance in public spaces) is intentional, with Zhu showing the importance of these streaming platforms in giving everyday people a voice, and exposing others to their lives and stories. This impact is largely felt with the film’s structure, starting with nondescript clips of construction and work life before easing into the “raw” liveblogging videos that Westerners could witness on Twitch IRL, Instagram Live, and the like. At two hours, though, Present.Perfect. is a film whose readily-understood message is outweighed by a novelty that wanes by the minute. While there’s more purpose to this film than, say, a Vine or TikTok compilation video, there’s certainly more enjoyment one can have when viewing actual live videos. Which is to say, there’s little reason to watch this film rather than simply visiting these platforms and experiencing the authenticity for oneself. There’s also less agency here than rifling through YouTube vlogs via the website’s recommendation system, as the act of moving from one video to the next on one’s own time is an act of participation in and of itself. Present.Perfect is thus an insightful film bogged down by its format: the “live” component of the subject matter proves contradictory in cinematic form, and the accessibility of live-streamed material renders the film nearly superfluous. Joshua Minsoo Kim

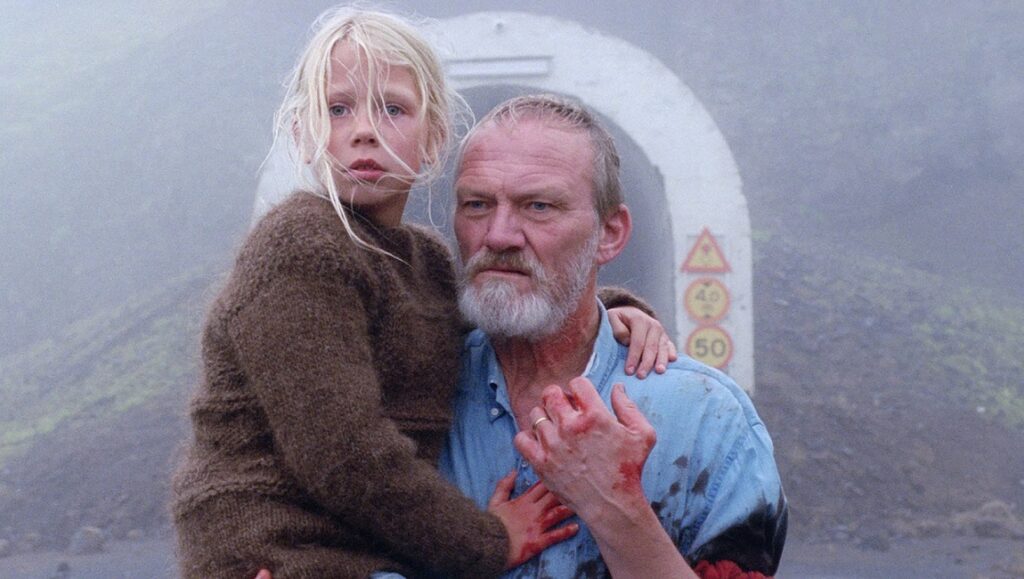

A White, White Day

Iceland’s Oscar entry this year, A White, White Day is a somber bereavement drama in which police chief Ingimundur (Ingvar Sigurdsson), who is grieving the loss of his wife in a car accident, stumbles upon vague evidence among her possessions that she has been having an affair with a local neighbour. Despite the suggestion that her supposed indiscretion could provide a “case” for this inspector to solve, the film shirks any sort of mystery angle, instead psychologically probing the man’s mental state, as well as his relationship with his daughter and granddaughter. For a character study, A White, White Day is as frustratingly closed off as its subject, as after all that follows, it never feels as if Ingimundur has been excavated. Director Hlynur Pálmason has a habit of cutting from scenes just as exchanges start to build, or shifting conversation topics away from matters of substance – three scenes in which Ingimundur sees a therapist offer relatively little about his character, while there is an active refusal to unravel any of his issues in a way that could be conceived as convenient. Resultantly, A White, White Day possesses some merit as a measured, convincing adult drama, but its continual opaqueness is often maddening. While films about grief tend to aim for realization and acceptance for its characters, Pálmason’s approach to this template feels way too uneven to generate much pathos, led by two intensely violent exchanges in the last act designed to confront the reality of his wife’s infidelity, but which feel distractingly jarring. A White, White Day eventually makes clear its message about both the difficulty and necessity of moving on from tragedy, and his approach here keeps the proceedings from becoming hackneyed. The issue is that, by this final stretch, Pálmason may well have alienated anybody from caring. Calum Reed

Comments are closed.