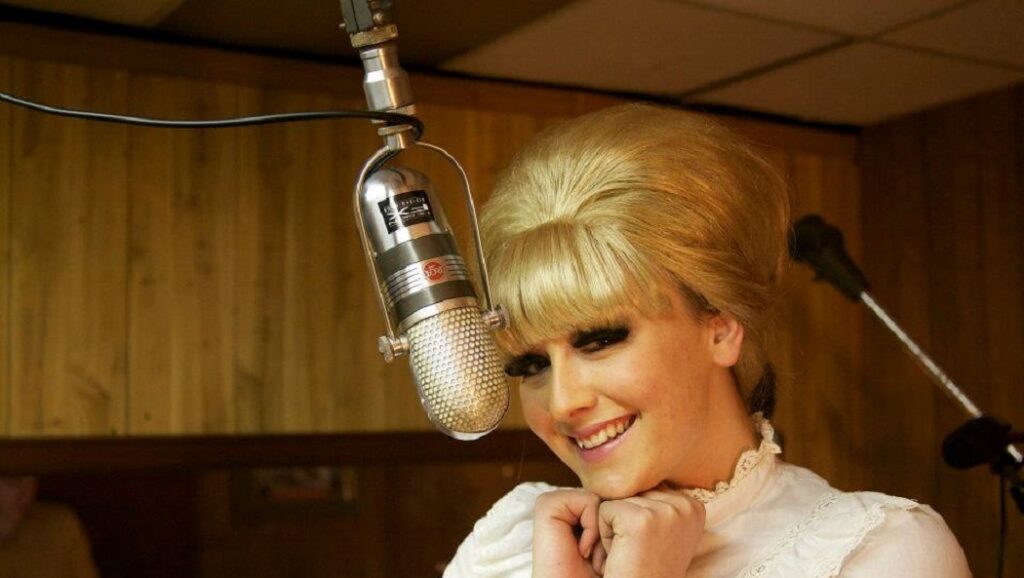

It’s only appropriate that Dusty Springfield’s 1969 record — which found the singer’s vocal sensibilities shifting over to R&B, and to more deliberately paced arrangements — took its time to accumulate the canonical status that it enjoys today. Comparing “Son of a Preacher Man,” the most successful single off Dusty in Memphis, to some of Springfield’s earlier hits makes it easy to imagine the toned-down vocal and instrumental performances on this album as something of a gamble. But the drama in Dusty’s voice proved well suited to changing trends in the music of the day. A softly flourishing sensuality is at the center of Dusty in Memphis, musically and lyrically — as opposed to the instant emotional impact of some of Springfield’s most popular work. This doesn’t stifle the singer’s trademark sentimentality, but rather, it gives it new meaning: no longer do Springfield’s songs express her own overwhelmed emotions, but rather they tap into the omnipresence of emotion and sensuality as a universal condition. The romantic bliss of opener “Just a Little Lovin’” extoles private pleasure (which informs the just-a-little-rose-tinted realism of that song’s chorus), and the album proceeds through a set that locates sensuousness in everyday life.

The album covers such an emotional range in dealing with its limited set of themes, so much so as to fashion a cohesive aesthetic, something more than the typical singles-and-filler dominating pop music.

“So Much Love” and “Son of a Preacher Man” accumulate resonance through their sequencing: the last verse of the latter song (“How well I remember / The look that was in his eyes / Stealin’ kisses from me on the sly”) is backed by resplendent horns, a climax that represents the ecstasy built-up over the pair of tracks, in addition to delivering its ecstatic standalone sentiments. The emotional heft behind “Son of a Preacher Man” — along with its enchanting melodies and harmonies — speaks to its success as a single, while pointing to the broader triumphs of this record as a whole, which express themselves through a replayability that was rare for pop albums of this period. The mournful lamentation of the last track, “I Can’t Make It Alone,” calls back to the feelings of wholeness and pleasure found on the album’s first song, in that the two are in almost complete emotional opposition, despite shared themes of sensuality and companionship informing all the music that’s sequenced between them. The languid and depressing “I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore” is expanded from its narrative exploration of a bad affair to a meditation on the internal effects of strained companionship. Even “The Windmills of Your Mind,” Dusty in Memphis’s clearest musical and thematic outlier, is similarly framed to evoke the psychological distortions brought on by solitude. The album covers such an emotional range in dealing with its limited set of themes, so much so as to fashion a cohesive aesthetic, something more than the typical singles-and-filler dominating pop music. Dusty in Memphis’s affective structure cements it as a classic, one that’s relistenable because — above all else — it’s feelings (those performed by Springfield, those that resonate through the musicianship, and those felt by the listener) that guide our experience.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.