It’s impossible to talk about 2023 without talking about Barbie and Oppenheimer, two very different films that became seismic pop culture sensations, crushing the box office while garnering no small amount of critical acclaim in the process. This is, of course, the Hollywood dream: four-quadrant pictures that appeal to huge swaths of the population, both packing movie theaters and generating awards chatter. Much like last year’s Top Gun: Maverick, these are the movies that are supposed to show how well the system works; i.e., people still love movies and will still venture out to theaters if you give them something worth going for. These are the kinds of movies that are going to save the cinema. Similarly obvious is that this approach articulates an extremely rosy view of the year in review. For every success story like the Barbenheimer phenom, there were even more failures; mighty juggernaut Disney floundered, releasing one overpriced bomb after another; the Marvel machine, a money-printing factory for the better part of a decade, has sputtered; and on that note, the entire superhero genre is showing clear signs of decline (witness the husk of the misbegotten DCEU limping through empty multiplexes). What will replace the superhero movie at your local theater? It’s hard to say, although based on this year’s winners, you can bet there will be more prestige biopics and a Mattel shared universe. The fact of the matter is, it’s a fool’s errand to predict what audiences will and will not respond to; as Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote years ago in his essential book Movie Wars, “Then and now, the operations of the media-industrial complex have been predicated on certain highly questionable assumptions about the audience, and charting box-office grosses to ‘prove’ those assumptions is merely indulging in a self-serving form of circular reasoning.”

The truth of the matter is, when pundits and awards prognosticators declare a year of film “good” or “bad,” they’re almost always talking about what played at large, mainstream movie theaters to some reasonable degree of success. Corporations, through mergers, acquisitions, tax write-offs, and the never-ending quest for shareholder value, continue to narrow avenues for genuine artistic expression in commercial cinema. We here at InRO aren’t staking out any anti-mainstream entertainment stance (you’ll find a couple of blockbusters and even a superhero movie on our consensus list), but we do hope that we can encourage readers to dig deeper, look further, and otherwise expand their horizons when it comes to what constitutes “the year in film.” Jean-Luc Godard once stated, “I like to consider myself an airplane, not an airport.” Film criticism can’t tell you, the reader, how to think or what to feel, but it can help you make a journey. The below list reflects InRO’s 2023 journey.

25. Full River Red

Zhang Yimou’s late-era resurgence is similarly positioned in relation to the stark landscape of post-pandemic Chinese cinema (“party’s over” vibes) as his iconic early-career run was to the boom era of the late-‘80s/early-‘90s. Knotted films like Full River Red methodically untangle the Gordian knot of the contemporary cultural, political, and technological landscape in the same way his elegiac early work struck a simple, resonant chord with the national mood of its time, and in turn, he is once again the county’s leading film artist in fusing “art cinema” with popular entertainment and the current of state-sponsored propaganda cinema that has been aggressively reasserted over the last decade. The film is Zhang’s latest return to premodern Chinese history — or more accurately, mythology — the subject for which he is most known, and it’s emblematic of the tact and artistry with which he has navigated the thorny filmmaking landscape, as well as his riveting new approach to narrative. Through a densely jagged and darkly comedic narrative, we watch a seemingly innocuous murder mystery unravel the fabric of the Southern Song dynasty in the aftermath of national hero Yue Fei’s execution. At regular intervals, Full River Red’s plot veers off course, startling expectations and making for a tonally dynamic experience. The plot unwinds organically through a minimalist, quasi-theatrical filmic mode that firmly plants one foot in the wave of films such as A New Old Play and The Eleventh Chapter, which are arguably the latest claimants to the lineage of “high art” in Chinese moving images. While that theatricality may seem to bode ill for a filmmaker known for being a visual artist before all else, frequent Zhang cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding proves once again that he is one of the finest DPs to ever touch a digital camera by imbuing every image here with energy. Full River Red’s populist invocation of one of the most resonant chapters in Chinese history also elegantly resolves the domestic political tensions that threaten to capsize every high-budget Chinese feature now, though it also reminds international audiences of the undercurrent of quasi-ethnic nationalism embedded in China’s national tradition, as implied by the universal identification with the Han Southern Song as opposed to the Tungusic Jin. — NOAL OAKSHOT

24. Unrest

As much an experimental inquiry into class struggle as a narrative film, Cyril Schäublin’s Unrest is one of the most idiosyncratic works to appear on the recent festival circuit. Its title refers both to the unrest wheel (a key component in watchmaking) and to the political unrest of the labor movement, and this dual meaning captures the film’s central idea. Set in and around a watch factory in the Swiss Alps in 1877, Unrest obsessively explores the rise of technologies regulating the time and space of labor. Tasks are timed to the second and recorded in ledgers; languages and currencies are carefully converted at the telegram office; and the factory workers don’t just build clocks, but use them to punch time cards and set their alarms. Schäublin’s film is concerned not only with how these regimes of regulation are used to discipline workers and intensify their exploitation, but also with how their seemingly scientific precision is, in fact, political artifice. Workers and managers contest not just the use and meaning of timekeeping and maps, but the idea of the nation state. When the town’s bourgeoisie stages a reenactment of an historic battle, anarchist workers argue that history is being rewritten to serve modern political needs. The film suggests this lesson can be applied to ideology and history more broadly, including ostensibly neutral technologies of work and governance. Unrest’s form echoes its themes: Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin is introduced as a protagonist — a cartographer serving another regulatory purpose — but it’s a red herring; he appears and disappears almost at random. Precisely composed, painterly shots alternate with anarchic ones that cut characters out of frame even as they’re speaking. This startling subversion of visual conventions asks us to see the contingency and invisible purpose of said conventions, and, by extension, to recognize all history and ideology as the subjective outcomes of class struggle. Schäublin’s ambiguously romantic ending suggests that it’s possible to put aside the ideology of the ruling class and build another world based on human need and desire. — ALEX FIELDS

23. The Zone of Interest

The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s fourth film and first since 2013, is a work with the power and complexity to outlast its temporal zeitgeist. An adaptation of Martin Amis’ novel of the same name, the British-U.S.-Polish co-production follows the domestic life of Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), commandant of Auschwitz. Glazer avoids the victim-centered emotional tragedies at the heart of most Shoah-period films, or the genocide genre more broadly, and opts for a formally daring dissection of evil’s ability to turn a soul inside out. Genocide happens in the background — as it often happens to the power players of our world who can so inconsequentially brush away catastrophe — and Glazer weaponizes the audience’s real-world awareness of the Holocaust to create a genuine horror film. The soundscape of screams and hallowed cries ensures the audience never forgets what lurks just beyond the seeing-eye distance of the idyllic Höss backyard; the effect of these sounds on Rudolf, as witnessed in the final scene of him vomiting on the stairs after being “honored” with the announcement of Operation Höss, ultimately rejects Hannah Arendt’s observation of the banality of evil at Adolf Eichmann’s trial. (The only other film this decade, or in any recent year for that matter, to terrify as efficiently with what’s offscreen rather than what’s on it is M. Night Shyamalan’s Old.) The actual wall of the concentration camp commands the horizon line for many of the outdoor scenes, but the camera never approaches or records the inner happenings of the gas chambers. It just stands erect, a monument to evil, and its mere presence terrifies precisely because of its real-world symbolism. By never turning his attention to the more human subjects of genocide, Glazer tests our capacity for passivity in the face of great evil. Only a few times does The Zone of Interest carefully depart from the banal workings and work-life of the Höss family for political action. Each time it does so comes at the initiative of a girl who lives near the Höss family, who sneaks out at night to hide food for the Shoah victims being corralled like chattel during the day (and whom we never see). Glazer and cinematographer Łukasz Żal use infrared images to alienate these moments of grace from the still and colored cinematography used in the rest of the picture: Auschwitz is too irreparably hopeless for the management of the bureaucracy of genocide and the hiding of apples in the dirt for to-be-murdered Jews to cohabitate. In the face of indifference, evil strips humanity of its colors. — JOSHUA POLANSKI

22. Limbo / Mad Fate

With Hong Kong’s last decade witnessing seismic changes in political life, filmmaking has been slow to adequately give sense to the ongoing nature of the moment. Documentary works portraying the agitation of youthful protestors have exhibited the city’s rage, but maturer voices have responded piecemeal. In this context, Soi Cheang’s (Accident, Motorway, SPL2, The Monkey King series) recent genre-inflected, Gordon Lam-led, serial killer diptych — Limbo (2021) and Mad Fate (2023) — mines local and international film influences to bring a deranged, poignant attention to the physical and mental states of the city’s occupants. In Limbo, finally hitting U.S. theaters in 2023 after years of languishing in distribution purgatory, honor is paid to disturbed CAT-III artistry, unhinged police pot-boilers (à la Ringo Lam’s Full Alert), and the brutal female-led stunt work (Dreaming the Reality, Angel Terminators 2) of a bygone time. Yet, what Cheang provides above all — no doubt courtesy of money and artistic freedom wrangled out of his Sun Wukong trilogy — is a near avant-garde, high-contrast, black-and-white cinematographic approach that foregrounds the territory’s rotted, garbage-laden lower depths as well as the lives of cop (Lam), killer (Hiroyuki Ikeuchi), victim (Cya Liu), and all others who traverse the near-dystopian landscape. These formal measures allow Limbo an almost metaphysical reflection on the commercial hub’s changing nature, as it becomes little but a capitalized landfill, the cracks of which are filled with the broken lives of locals and immigrants alike and from which death remains the final freedom. Conversely, Cheang’s other 2023 release, Mad Fate, offers an intertextual, giallo-inspired project exploring the city’s intergenerational and class rifts with an impassioned attunement to the youth’s despair-suffused predicament. Following an amateur, unstable Daoist exorcist’s (Lam) attempts to change the “destinies” engulfing those willing to pay, the film follows as he becomes entangled with a sociopathic, murder-hungry young delivery man whom he decides to cure after his previous customer is murdered by a mysterious killer. From that setup, a crazed plot of soul transference, shared trauma, and divine warfare familiar to Milkyway Image aficionados unleashes, as Mad Fate joins the recent Detectives vs. Sleuths in empathetically adjudicating Hong Kong’s conflicted present. Seeing an elder generation grapple with the younger’s rage as their future contracts is touching, and Cheang’s choice to converse with other filmmakers, prior interests, and international horror gives Mad Fate a demented power in finding liberation: not in death, but in life lived once more through collectivity, shared pain, and defiance of the gods. — MATTHEW MCCRACKEN

21. Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani

Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani (“Rocky and Rani’s Love Story”) probably isn’t the most important movie of 2023. It breaks no new ground in cinema, and it does not soberly examine such weighty themes as the destructive potential of scientific advancement or the planned genocide of whole peoples by ordinary citizens. It is, in its first half, a romantic comedy; in the second, an intergenerational family drama. The film’s plot mechanics, likewise, would be unremarkable in any random sitcom from the past 50 years. That being said, it is nonetheless quite simply the year’s most delightful film, and quite possibly the best, which might be the same thing. Ranveer Singh and Alia Bhatt are the eponymous star-crossed lovers — he’s a himbo with a heart of gold, not too bright but deeply sincere; she’s a hard-nosed news anchor, bright and ruthless. They meet cute after Rocky’s grandfather, who rarely speaks after a tragic accident, mentions the name of a woman who turns out to be Rani’s grandmother. The two elders had a relationship in the past, and their grandchildren work to reunite them while falling in love themselves. But they come from two very different families, and before getting engaged, they agree to a trial arrangement: each will spend three months living with the other’s family; Rocky with Rani’s progressive and intellectual parents, Rani with Rocky’s domineering grandmother who lords over their mansion, her son, his wife, and Rocky’s sister. After plenty of dramatic incidents, each side learns a little bit from the other, and it all resolves in unequivocal happiness. What makes Rocky and Rani sing, so to speak, are the performances (Singh, in particular, is brilliant, with his “limitless hotness and strange English,” but Bhatt and Jaya Bachchan as Rocky’s grandmother are terrific as well — really, the whole cast is exceptional) and the specificity of character details, successfully building out each member of the household into a real person with their own hangups, quirks, and struggles. When love finally does conquer all, it feels like a hard-won victory constructed from a series of smaller triumphs, each one real and each one personal. It’s something the broad expanse and runtime of a Bollywood film can provide, and director Karan Johar makes use of every second of the film’s runtime. If Rocky Aur Rani feels overly familiar (recalling such KJo or KJo-adjacent classics as Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge and Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham…) or naïve in its belief in the power of love to overcome generational and ideological differences, that may just be because there’s no difference, for Johar, between Bollywood history and the real world. — SEAN GILMAN

20. Human Flowers of Flesh

Helena Wittmann’s Human Flowers of Flesh all but traverses an ocean in its efforts to create a sensory experience for its audience, gently bobbing in and out of narrative, setting off with a ragtag party of international persons and coming to land as a critique of French colonialism. The story follows Ida (Angeliki Papoulia) and a crew of men charting the path of the French Legion to their former headquarters. Fluidity comes to mark the film’s ethos, as Human Flowers follows in the line of cinema that seeks evocation over exposition, a meditative rumination on the ocean’s movements and France’s imperial bent. It’s on an undeniable current to a confrontation with this legacy, but in the moments that it’s not, Human Flowers revels in the water it traverses. Wittmann’s camera does stunning work, 16mm film lending a tangible quality to the pervasive sea and a texture to the light it captures. In a particularly stunning sequence of underwater photography, the audience is taken deep under the cover of darkness to the watery tomb of a fallen plane, now teeming with microscopic life; Wittman’s general experimentation with film’s chemical processes makes for some of the most fascinating images and thoughtful narrative devices. But for as many parallels one can draw between Human Flowers and the experimental world, Beau Travail marks its most potent influence — the untrained eye might even mistake some mirroring sequences between the two’s depictions of the French Legion. In a final twist, it’s revealed that the legionnaire Ida has been trailing is Galoup, played by Denis Lavant, here bearing the same name as the character he plays in Claire Denis’ heralded work. Galoup and Ida’s interactions are short, and in the film’s final minutes, Human Flowers of Flesh unfolds itself not as a story about these legionnaires, but rather pointedly about their shadows, scattered across the sands they leave behind. — JOSHUA PEINADO

19. The Sweet East

For a film so entrenched in the grotty nooks, crannies, and playgrounds of our present sociopolitical American moment — the tenor of which is echoed in director Sean Price Williams’ grungy yesteryear aesthetic — The Sweet East is remarkably reserved with regard to soapboxing any discursive agenda. Williams and rascally screenwriter Nick Pinkerton aren’t shy to indulge provocative metaphor or to cast a glimmer of mirror-world absurdism over the film’s proceedings, no doubt drawing from the traditions of mid-century absurdist literature and its funhouse filter, but there are no value judgments to be found in the recognizably American waypoints of the film’s various movements. Outright caricature is rejected for its limiting nature, and instead this sandbox survey of fascists hiding behind intellectual armor, artist-types who seem to have all but absconded from reality, and rave-happy fundamentalists whisks stereotype and human being to the point of indiscernibility, lending the film a fevered, dreamlike texture that is likewise aided by our guide Lillian’s (Talia Ryder) seeming imperviousness to her near-surreal encounters. Indeed, though the mainly male gauntlet of incidents that she endures bleeds danger into even the most mundane developments, Lillian possesses an evident power, sometimes even seeming to bend reality to her will when required and serving up a stealth feminist spin on the picaresque. The whole thing operates rather like a circuitous Odyssean journey, though one that is notably ambivalent of destination and which regards each new circumstance less as obstacle than opportunity. In shaping The Sweet East, Williams and Pinkerton smartly pull from such easily identifiable traditions of literature and narrative structure not to underscore but to temper the rather gauche inflections of the film’s rhetorical fodder, setting aside lesser instincts to satirize and moralize in favor of a riotous, savvy study of the ways that the rack, ruin, and romance born of the American experiment are ever in conversation. — LUKE GORHAM

18. Queens of the Qing Dynasty

The post-intake opening of Queens of the Qing Dynasty, set deep inside a Cape Breton hospital, could connect lead actor Sarah Walker with other high-voltage performances of institutionalized life, whether it be the gliding POV of Joan Crawford in Possessed or the improvised creative distance of Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence. Indeed, the case could be made that Ashley McKenzie’s second feature is a rival for the heights of those films’ intensities, but the manner of how it arrives at psychological explanations and dramatic catharses for its characters is altogether something else. Star (Walker), a patient, and An (Zheng Ziyin), a volunteer caretaker, each experience the constraints of normative behaviour models applied respectively by the healthcare and immigration systems of the Canadian state. McKenzie’s film understands that to merely prove the existence of their pain or intelligence would be beside the point; rather, in its jarring sense of montage, each shot and sound jolting the next, Queens of the Qing Dynasty creates the effect of reality breaking apart, in such a way that coded banter, virtual reality, and electronic feeds — texts, animations, and blasts of music — are formed by and respond to the film’s duo in a varyingly plastic manner. (In this way, McKenzie’s film is consciously influenced by the ideas of the musician SOPHIE, whose collaborator Cecile Believe features on the soundtrack.) Rather than a psychodrama, perhaps the only other film that readily comes to mind for comparison is Jia Zhangke’s The World — specifically, in the way it utilizes animation. McKenzie’s characters take flight too, yet this sensation carries over even to their super closeup-framed dialogues in the isolated world of Cape Breton Island. They acquire each other’s wavelengths — inexactly, and at times distressingly — but their visions combine in such a concentrated way that it’s as if they are reversing the polarity of modern psychoanalysis, rendering professionalism null and instead respecting the unknown capacities of both psychical and physical reality. — MICHAEL SCOULAR

17. Ferrari

At one point in Michael Mann’s Ferrari, his first film in eight years, Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) addresses his team of racers before they embark on the 1957 Mille Miglia, a 1,000-mile race that traverses a huge swath of Italy. “We all know it’s our deadly passion. Our terrible joy,” he says, preparing the men to risk whatever it takes to complete their trek. He adds, “If you get into one of my cars, you get in to win.” It makes sense that Michael Mann would be obsessed with the story of Ferrari, the man and the car, spending the better part of three decades trying to get this film made in one form or another. Enzo, as portrayed by a strikingly precise, occasionally stentorian Driver, is a man driven to succeed, but only on his own terms. A details-oriented task master, Enzo demands perfection from himself, his engineers, and his drivers. Of course, Mann himself has a similar reputation, and it’s almost impossible not to think of the film as a kind of auto-critique. Mann’s entire filmography is preoccupied with professionals who pursue their goals with a single-minded rigor, often to the detriment of all else. Far from a standard biopic, Ferrari is a movie preoccupied with death, made by an aged auteur who seems increasingly aware of his own mortality. The specter of Enzo’s deceased eldest son haunts the proceedings, as well as the ghosts of fallen friends from his own days as a racer. Enzo (and Mann) find the beauty in the sleek, precise mechanics of these automobiles, while simultaneously being aware of their deadly power. Steel and glass and horsepower are an intoxicating mixture, the allure of danger finally reaching its apex in a distressingly violent crash that stands as one of the more disturbing moments in Mann’s filmography. Penelope Cruz stuns as Enzo’s equally fierce, determined wife, who puts up with Enzo’s philandering but refuses to allow his tunnel vision to ruin their shared company. Ferrari is a movie about racing, yes, but it’s also a movie about making movies, a kind of mea culpa from Mann that plays like a belated apology for a lifetime spent pursuing perfection. It’s a great film from one of the great American directors, and a key late-style text that suggests the heavy burden that is the quest for an impossible ideal. — DANIEL GORMAN

16. Afire

Christian Petzold’s latest is quite the panoply of film genres, concerns, storylines, and characters. It’s technically a vacation movie, where a self-serious writer simply cannot bring himself to relax and write, much to the chagrin of his friends, who wish for him to relax, and his possible publisher, who wishes for him to write. It’s also something of a Hitchcockian (the comparison can’t escape Petzold’s work) romance, though it goes about as well as those normally do for their characters. Finally, it’s an apocalypse — both in the English sense of a fiery ending and its original meaning tied to “revelations,” as our central writer-figure contends with what’s really important in his life and his work. Change is hardly ever easy or pleasant, and good writing is a process of lifting oneself out of a pit of stagnation with a good kick in one’s ass. And this, Afire manages to mix and meld such gravitas and low-stakes buffoonery with ease. There’s a grisly death sequence, but a certain once-pleasant party scene fills even more dread — a sure sign of a careful and wise director. Many words have been spilled about our dear writer Leon’s (Thomas Schubert) relation to the worst part of the artist’s soul that may constantly threaten to bubble up in polite and supportive company, but the supporting cast here manages to stir up romances both real and potential as in the best of Rohmer’s work. It’s shot both literally and like a ghost story, as Paula Beer’s Nadja — a specter first borne of whispers — appears and disappears in window frames and introduces herself as if having emerged from a Henry James tale. But Petzold masterfully creates in Leon a summertime Scrooge, a man who at last realizes what wonders lay before him, swimming above all the sadness that still remains. — ZACH LEWIS

15. The Boy and the Heron

“Barbenheimer” aside, no film this past year bucked a conventional marketing strategy quite like Hayao Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? While we in the States received several trailers and posters for the film under its noxious international title The Boy and the Heron, audiences in Japan were fed scant information about the beloved animator’s first project in 10 years (an engaging vagueness echoed in its domestic title). What we all received was an unmistakably personal statement on the complicated act of radical creation from the ashes of destruction. For Miyazaki, creation stems from communion with the past. The title foregrounds a connection to Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel of the same name, and like his central protagonist, Mahito, Miyazaki was gifted Yoshino’s seminal bildungsroman by a mother who perished in a firebomb raid during the Second World War. Miyazaki and his onscreen avatar subsume the thematic skeleton of Yoshino’s novel into a complex meditation on how their ethical and political convictions are shaped by the women in their lives. Yet viewing The Boy and the Heron through a strictly autobiographical lens doesn’t neatly account for its barrage of allegorical avians. Molded into man’s image, it’s hardly surprising these birds ultimately rebel and destroy a precarious social construct facilitated by modernity. What Miyazaki’s oneiric dimension ambivalently posits is a historical cycle where Japan’s trajectory from the Meiji Restoration to the cataclysmic end of World War II could very well indicate our eventual self-destruction. Like Yoshino, Miyazaki suggests the onus for breaking that cycle lies with the next generation. Yet The Boy and the Heron exudes the harsh wisdom of that lesson with the boundless grace of an artist using his medium to envisage the harmony which eludes us. Such harmony doesn’t insulate us from horror, but instead gently arms us to confront it with a simple, provocative question: How do you live? — NICK KOUHI

14. Anatomy of a Fall

Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall opens with the expectation of an affair. Author Sandra (a brilliant Sandra Hüller) begins by sidetracking the interview of a young academic, unable to talk about herself outside her writing. The two women’s conversation, punctuated by too–long glances and an easygoing laughter not seen later, is cut short when Sandra’s husband Samuel (Samuel Theis) blares a steel-drum cover of 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.” from above, over and over. The urgent, punctuated piano over the opening credits’ slideshow of family photos — of the actors during earlier, happier times — encourages us to take every bit of this intro seriously. After all, it’s only an hour later when Samuel is found dead. The court reads into this as an overthinking cinephile would. Since Samuel’s fall from the attic is inconclusive, with blood spatters in all the wrong places, a scolding attorney unravels what we have seen before — was this flirtation a start of another affair, and was the music, the purportedly misogynistic lyrics of its original song, a provocation? Does any of this matter? The question is not whether Sandra did it, but whether it matters. If Anatomy of a Fall’s court is going to center perceptions of Sandra’s own morality, divorcing her from the truth of her own marriage to lavish in her bisexual infidelity, then her Judgment Day may be equally abstract from linear happenings. Though the film’s central question, the “Did she do it?” advertising punch, is never answered, very little ambiguity is left in the circumstances of the fall. Anatomy itself implies an objective, veiny truth. Director Justine Triet and her partner Arthur Harari’s script instead relies on the subjectivity of a truth: whether a reasonable doubt is beyond our concept of reality. This case is not solved by evidence of a forceful hand on Samuel’s shoulder, at least not physically, but by a child’s utilitarian judgment of what will serve him best, even if each option worries him. The three witnesses to Samuel’s death and its immediate surroundings are Sandra, vision-impaired son Daniel (Milo Machado Graner), and a leering moral judgment from a legal system initially more interested in the narrative of Samuel’s death than its facts. Where Sandra’s books intersect with reality, the court then views autofiction as evidential. It’s no coincidence that the actors share names with their characters, that the family photos of Hüller and Theis over the credits aren’t from this story — we are to fall for a literary red herring the way the court reads Sandra’s fictional murderess as a mirror. The court’s greatest focal point in the trial of the couple’s marriage is a recording of an argument not long before the day Samuel dies. In it, they each blame the other for their problems: Sandra’s perceived entrapment in a rural area with a language that is not her own, and Samuel’s inability to find time within himself to write. Most interesting to the court, though they are blind to its articulation, is that the couple swap typical gender roles, with Sandra as an absent, work-focused parent and Samuel filling what would usually be a feminine role at his own leisure. The court’s understanding of family wavers and, through every revelation, grows more fraught in ruling what constitutes the remains of a family, what the burden of proof is for a crime no one asked to investigate. — SARAH WILLIAMS

13. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

For a while, it seemed like Disney’s ongoing assembly line of Marvel product was essentially a license to print money. But as we sit today, the studio may have to rethink its strategy, since apparently even diehard fans are growing tired of the MCU’s strange combination of complexity and sameness. If they’re smart, Marvel will divert more of its resources to animation. The Miles Morales Spider-Man films are virtually in a class by themselves in terms of combining IP mythology with bold formal invention, and latest entry Across the Spider-Verse functions as a sort of Rubik’s-Cubist canvas of ever-evolving possibilities. The instability of the multiverse both gives and takes in this world, since the capabilities that can alter a desolate future are precisely the ones that invoke another unexpected form of doom — Spider-Man’s “Appointment in Samarra,” if you will. But Spider-Verse takes the additional step of making the absolute commitment to official lore (i.e., “canon events”) into a form of oppression in itself, something Miles is just brave and bullheaded enough to try and defeat. There’s nothing so unusual about a superhero flouting convention in the name of individual exceptionalism, but I don’t think that’s what’s happening here. Instead, Miles and Gwen Stacy are fighting on behalf of creativity and imagination, possibly the only forces that can outstrip corporate conformity. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

12. The Plains

The rare English-language debut film of recent years to achieve unequivocal greatness, David Easteal’s The Plains takes old Kiarostami-inspired notions of cinema — as a series of repetitive car rides — and blows them up to a three-hour length. The audience remains in the backseat of a car commuting home from work, a passively observing passenger, for nearly the film’s entire runtime. Middle-aged lawyer Andrew (a retroactive self-portrait by the actor Andrew Rakowski — also the car’s driver) isn’t much more active in shaping his own life. As conversations unfold with his wife over the phone or with his carpooling younger coworker David (Easteal, presumably also “playing” a version of himself), we witness (and perhaps take on some of the baggage of) the inner life that can unfold when you try and find variations in a looping routine. His mother’s slow death from dementia, and the resulting need to have to take the same trip home every day so he can pay the bills, are what keeps him perpetually car-bound. His sympathetic fellow traveler wants to share in this act of burden-sharing via stories and anecdotes, and the two help each other ease their loads for a while. (David’s own issues are more oriented toward his romantic relationships.) We’ll never know for sure if Andrew fully succeeds at chipping away at his weights, but there’s a sort of freedom and spontaneity to be found in the camera being locked into the seemingly strict form of this commute’s backseat, the traffic and weather changing slightly and offering both viewers and commuter something slightly different to view with each passing day. One of the film’s two most poignant moments could only be achieved within a car, and the other only by getting out of it. The former finds Andrew sharing a song with David via the car speakers, and it’s the simplest way of using music to connect with others: a song title reminding you of a specific person. The latter finds Easteal switching from his unmoving static setup to a drone camera that moves in every direction, finally finding the middle ground between Andrew’s desire for freedom from his burdens and the need to maintain life’s more profound and personal connections. We take a flight across the titular region (set in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia), and the camera settles on the previously unseen faces behind the conversations and music, the final missing pieces of the puzzle. — ANDREW REICHEL

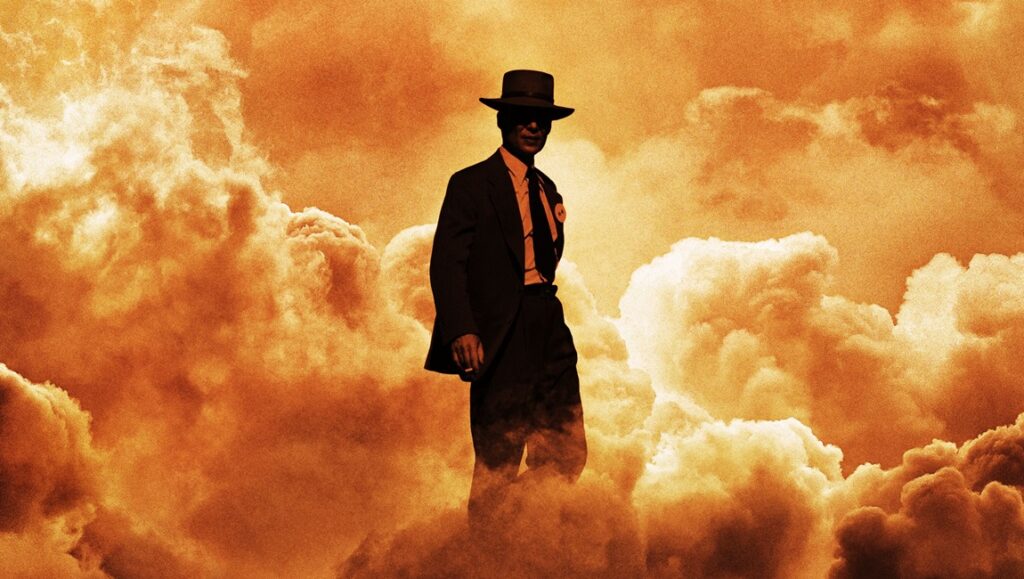

11. Oppenheimer

The term “compartmentalization” is spoken half a dozen times over the course of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, exclusively in terms of rigid security protocols which attempted to silo each faction of the sprawling Manhattan Project from being too intimately aware of what anyone else was working on, lest the entire plan be leaked. It’s also not so secretly the subject of the film, even more so than exploring the life of its title subject, J. Robert Oppenheimer: theoretical physicist, laboratory director at Los Alamos, and widely regarded as the father of the atom bomb. The film is about nothing less than humanity’s endless capacity to rationalize, equivocate, and self-delude; keeping two competing thoughts in its head at the same time while still willfully blinding itself to the consequences of its actions. Oppenheimer wasn’t really a Communist, he merely organized labor, attended meetings, read the literature, shared a bed with multiple past and present party members, and funneled funds to oppose Franco in the Spanish Civil War. The Manhattan Project didn’t actually play a role in the deaths of over a hundred thousand Japanese civilians, it merely built the most powerful weapon in the history of the world — initially intended to stop The Third Reich, which had already fallen by the summer of 1945 — and trusted it to the itchy trigger finger of a U.S. government looking to justify its multi-billion-dollar investment. Oppenheimer wasn’t punished by that same government for his inconvenient dissent against the escalation of the nuclear program, he was merely denied top secret clearance, effectively ending his career; a bureaucratic resolution, not a punitive one. Drawing from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s nonfiction account, American Prometheus, Nolan’s vision of Oppenheimer is that of a genius who foresaw a quantum world and its theoretical capacity to usher in a new era of global peace, yet naïvely failed to appreciate how his discoveries would be exploited by reckless nations. And ultimately, the film is the story of a man who came to believe he had destroyed the world and whose only recourse was to let the world destroy him back as a show of penitence. It’s a dense, chatty, three-hour film, half shot in black and white, primarily spent in conference rooms, Senate confirmation hearings, university classrooms, and army barracks that demanded to be seen on the biggest screen possible. It also dominated (along with its pink-hued release-date-mate) pop culture, grossed almost a billion dollars worldwide, and is even being credited with resuscitating physical media. All this with nary a superhero or video game character in sight, while sending the audience back out into the world with the message that the end is nigh. Oppenheimer the man, destroyer of worlds. Oppenheimer the film, savior of cinema? — ANDREW DIGNAN

“>

Comments are closed.