The Ross Brothers’ latest is a uniquely heady, tonally dexterous work that operates at the intersection of documentary and fiction.

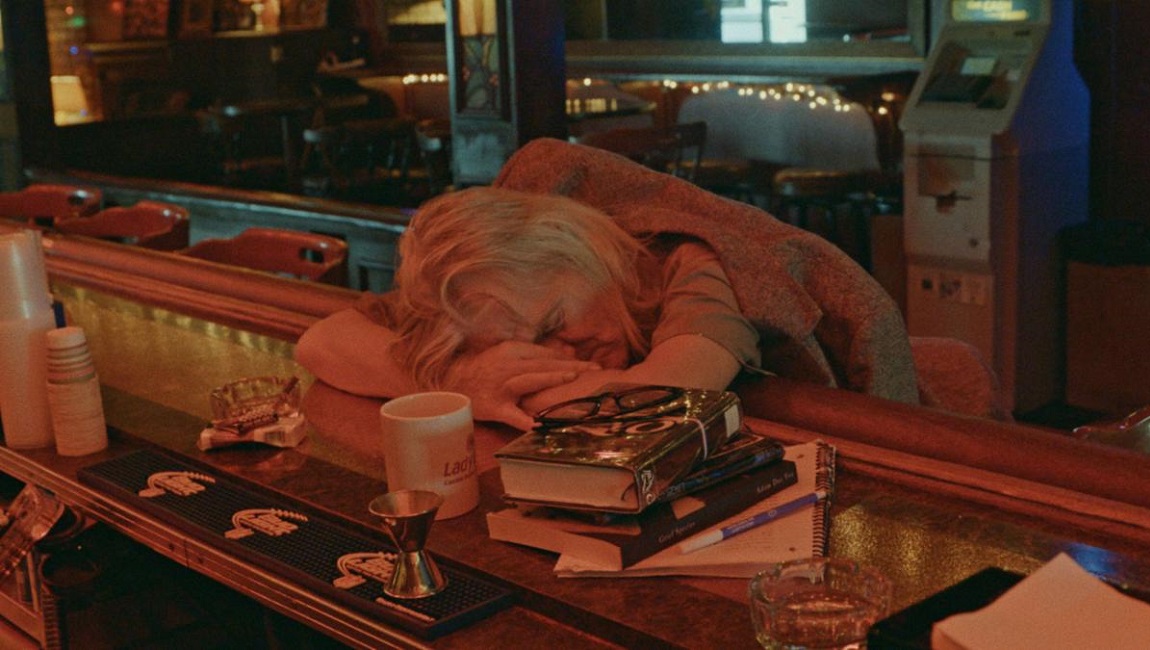

An official selection of this year’s Sundance U.S. Documentary Competition, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets chronicles the final business day of a Las Vegas dive, the Roaring 20s, where a group of regulars — mostly fast friends and familiar faces — gather for one last bibulous bash. Except the ostensible regulars are really strangers to each other (amateurs selected from various casting sessions at bars), the Roaring 20s isn’t closing, and the bar is actually located in New Orleans, the home base of directing duo Bill and Turner Ross. For the Ross brothers, then, the non-fiction categorization is more of a statement of intent, allowing them to thumb their noses at some of the more ill-conceived conceptions of the documentary/fiction dichotomy, while also acknowledging the self-imposed boundaries of their methodology. With the notable exception of some interstitial lo-fi glimpses of Las Vegas (for real, this time), most of the film’s footage was shot with two cameras, in real-time, over a single 18-hour shoot. In addition, the directors guided the film’s rhythm and flow using a checklist for entrances, exits, music cues, and other desired happenings or in-film events. And needless to say, the booze — and there’s lots of it — was unquestionably real.

Turner Ross summed up the project’s design as “an alchemy of the people,” and the result is indeed a uniquely heady brew. The prevailing tone is comic: the farce-like structure, the barflies’ vivid personalities, and Bill Ross’ sharp, punchy editing ensure that the proceedings are largely raucous and fun. But there’s no shortage of conflict, either, most noticeably rooted in generational tensions: one of the most prominent patrons, a local theater actor named Michael Martin, acknowledges boomer responsibility at one point, then later has it out with an argumentative thirty-something who looks a lot like Elliott Gould. Throughout, there are also various references (on television screens, in dialogue, on moldering signage) to the contemporary homogenization of American cities (“Fucking Celine Dion can have it, I’m moving,” says one person), which are in turn contrasted to certain myths that the nation is founded upon. A particularly pointed inclusion has Jeopardy on one of the televisions, with all three contestants stumped by the first question in a category titled “Native American,” the last column on the board.

Such explicit socio-political signposting, though, can feel rather strained. In any case, it’s far less interesting than the directors’ quicksilver modulations of not just tone, but also visual texture. Bill Ross has said that their films are “really just about the images in our head,” a statement that’s borne out by the neon-soaked, hyper-clear digital of the main bar footage, the impressionistic Las Vegas interludes (shot with a Panasonic DVX100b), and the low-grade security camera footage of a scene involving fireworks. Even the closing credits, which include photos taken over the course of the shoot, highlight the project’s impressive visual range (no small accomplishment given the time-constrained shoot). Significantly, though, the Ross brothers’ formal adaptability does not at all obscure their way with character, and amidst the bar’s boozy chaos, the film manages to strike some genuinely touching chords. Towards the end, a regretful Michael tells a young musician: “There is nothing more boring than someone who used to do stuff and just sits in a bar.” True enough, perhaps. For at least as long as Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets lasts, though, you may be convinced otherwise.